“I have found a paper of mine among some others,” said Goethe today, “in which I call architecture ‘petrified music.’ Really there is something in this; the tone of mind produced by architecture approaches the effect of music.”

Johann Peter Eckermann, Conversations with Goethe [tr. John Oxenford]: March 23, 1829

Bostonian writer Lynda Morgenroth (a distinguished alumna of my alma mater, Boston University), in an essay published in the 2004 anthology The Good City, remarked:

"living...in a place rich in history, architecture, and human endeavor, can impart meaning and dignity to our efforts, and soothe the small but continual humiliations that come to every life. In a city such as Boston, we see examples of perseverance, accomplishment, and inspiration in the buildings... Through all our seasons of failure, foolishness, and blunted hopes, there is, in the community of the great city, the balm of respectable association and the consolation of beauty."

These comments about architecture stay with me: the idea of beauty as a means of promoting and sustaining human dignity — beauty as a form of justice — seems to me to be at the core of understanding the arts and their meaning and purpose in human life. Both architecture and music, at their best, impart beauty — and therefore dignity — to everyday existence, be it in the physical, tangible form of buildings, or in the aural, vibrational form of sound.

It has been proposed that Guillaume Dufay’s motet Nuper rosarum flores from 1436, written for the consecration of the Duomo in Florence, contains rhythmic proportions in its music that mimic the mathematical dimensions of the church building; although that hypothesis has not held up well under further scrutiny, no one can deny that the structures of musical works and architectural edifices bear fundamental similarities. We cannot ignore the power in the intentional blending of creative endeavors. Richard Wagner strove to bring into existence the idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk — a “total art work” that would combine all the arts. We can scarcely even imagine opera and theater without architecture, whether in the concave sweep of the Theatre of Epidaurus, the spectacular stagings of the operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully during Louis XIV’s reign, or the astounding technological wizardry that goes into productions we can enjoy right here in Washington today.

We may never know with certainty the progenitor of the familiar phrase, “Writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” but I frankly think and hope that it’s true — insofar as I consider both writing about music and dancing about architecture to be good and worthy things to do.

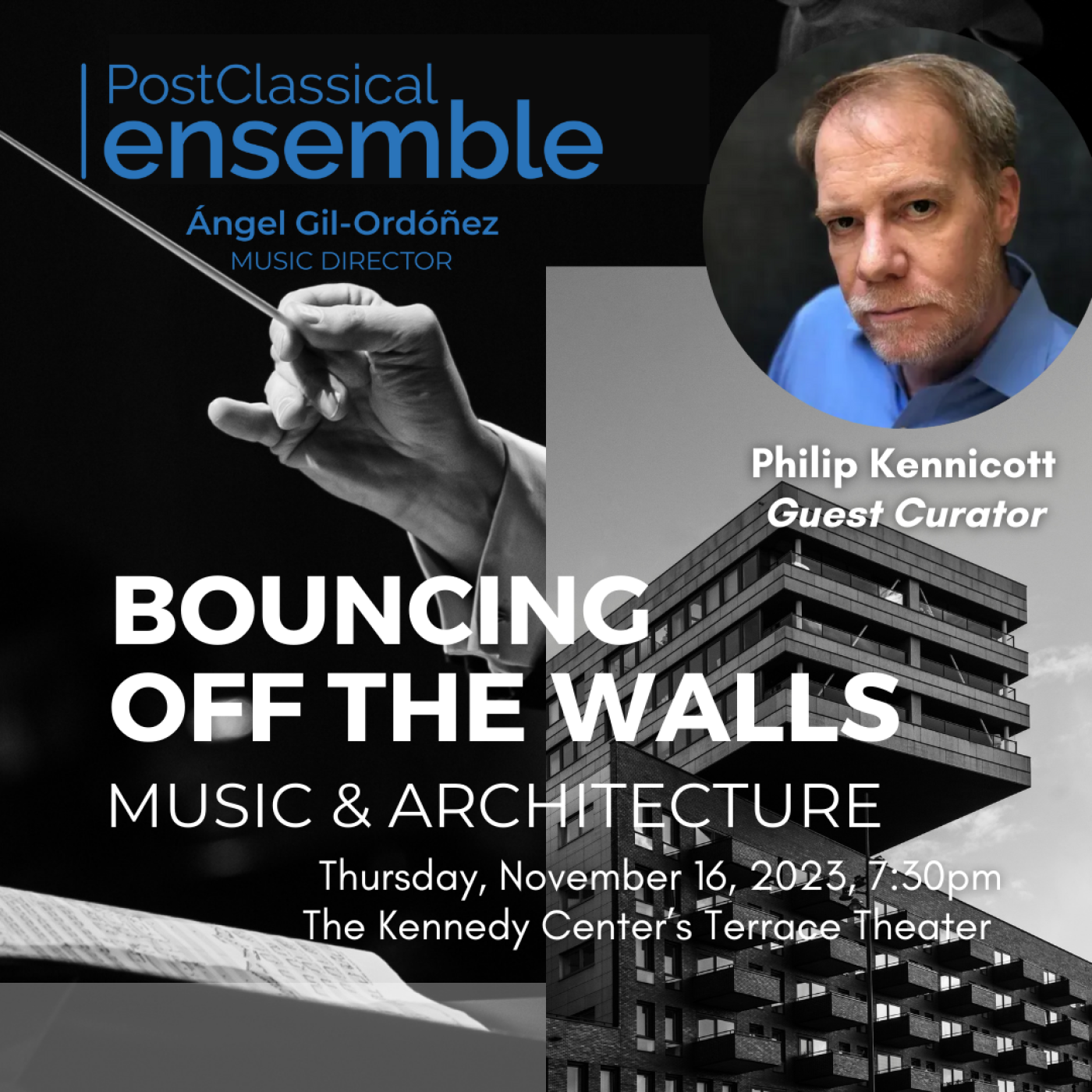

I think about these things as I read this interview with Ángel Gil-Ordóñez and Philip Kennicott about their upcoming PostClassical Ensemble concert, Bouncing Off the Walls, on Thursday, November 16 at The Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater.

Philip, you've written about both music and architecture; can you talk about how you see the two as interrelated?

PK: I started with the vocabulary they share. Words like harmony and dissonance, form, structure and ornamentation, make sense to both musicians and architects. There’s been a long history of assuming that because music and architecture are both dependent on mathematics and ideas of proportion, and because they also share a language, that they must be fundamentally connected. Think of that famous line by Goethe everyone loves to quote: Architecture is frozen music. I love the poetry of that thought and it will be our starting point for the concert. But then we’re going to move on and try to look a little more deeply about both the similarities and the differences between these two realms of creativity. Consider this obvious difference: A badly constructed piece of music may be boring, or annoying or forgettable, but a badly built building can fall down and kill people. So, clearly, there are some distinctions to be made.

What inspired the idea for this concert? Is the relationship between music and architecture something you've long wanted to explore or is it a more recent idea?

AGO: I have always been interested in the relationship between the two arts. I like to compare the musical score to a blueprint of a building: both the musician and the architect are able to imagine the sound/space by looking at them.

Angel, what insight or creativity was Philip able to bring into this concept?

AGO: Philip Kennicott is the reason I decided to finally explore this relationship among the two art forms. I have always admired his writings on architecture and art in general. I felt he was the perfect partner for such an adventure. We are having a lot of fun and I am learning a lot. We cannot wait to share it with the audience on November 16!

Philip, what was the process like for you to step in as a special guest curator?

PK: This has been an enormous amount of fun. Angel first proposed the idea a few years ago, when the PostClassical Ensemble gave a beautiful, outdoor performance of Stravinsky’s L’histoire du Soldat during the pandemic. I had been thinking about the connection between architecture and music for a long time and planning to write something about it…but “planning” in the sense that writers often plan to do things, in the indefinite, far-flung future between tomorrow and never. But here was a chance not just to write about the connection, but to explore it with actual musicians and for an audience. With a musical ensemble to help underscore and demonstrate ideas, there was a new set of possibilities. If I want to show that Haydn once composed a classically “symmetrical” piece of music, well, now we can perform that piece, and let people decide for themselves if they can hear the symmetry. This is so much more engaging than just putting ideas on the page.

How did you come up with the right composers and pieces? Were the selections immediately obvious to you or did you have new discoveries during the curation process?

PK: The individual musical selections weren’t immediately obvious, and Angel and I worked together to figure out those details. But the broad musical ideas, or categories, were clear almost from the start. I was thinking in terms of architectural and cultural history, so I wanted something that would represent the sound world that Europeans lived in for millennia—the giant cathedral or basilica for which so much sacred music was written. But then we also needed to show this astonishing transformation in the 18th century, when there’s a new audience for music outside the church, an audience that begins to gather in taverns, and large rooms, and then in musical halls specifically built for this new music and its unique acoustic. There is another transformation that comes with the spread of industrialization and the era of mechanical noise and radio. So, we needed something from the early modernist period in music, and I think we have the perfect piece: Webern’s Five Pieces, Opus 10. There are also some surprises and when Angel asked what I’d love to hear if I could pick anything, I said, The William Tell Overture. But you’ll have to come to the concert to understand why.

Have you arranged any of the pieces in some way to take advantage of the architecture and surroundings in the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater? If so, can you talk about what the process of arranging was like and how the audience might experience that?

AGO: More than choosing music that adapts to the acoustic conditions of the Terrace specifically, we want the audience to be transported to the spaces where the music was heard at the time.

PK: Ideally, we would perform each piece in exactly the sort of room for which it was originally composed, but you can’t fit a giant basilica, an opera house and the music room of the Esterhaza palace all into the Terrace Theater. But what we can do is talk about those rooms and their architecture, and the larger idea driving this project: Aural Architecture. I didn’t invent that term, but I want to explain it, and I hope, leave people more interested and more engaged with the way we make sense of the world, including the built environment, with our ears, not just our eyes.

What are the ideas or connections that you hope people will come away with from this concert?

AGO: We hope to create the interest in the audience to listen to music in a different way. On the one hand, the effect of music in a specific space. On the other hand, music and architecture are crafts, and both share structures and rules.

PK: When you go into a museum and see a famous painting--let’s say it’s “iconic”—you have to do some serious work to see it afresh. You need to disentangle it from your memories and expectations and all the cultural baggage it carries. The same is true for both music and architecture, but we often get rather lazy about experiencing them in novel ways. Buildings become so familiar we hardly see them, and with music it can be worse: If it doesn’t sound exactly like our favorite performance, we feel a sense of pique. So, the main goal is to invite people to see and hear things anew. I’d also like architects to think more about how their buildings sound, and for everyone to think more about how music grounds us in the larger sonic or aural world.

Learn more about the concert and get tickets here: https://www.kennedy-center.org/whats-on/explore-by-genre/classical-music/2023-2024/bouncing-off-the-walls/

Angel Gil-Ordóñez is Music Director of PostClassical Ensemble, Principal Guest Conductor of New York’s Perspectives Ensemble, and Music Director of the Georgetown University Orchestra. He also serves as lead advisor for Trinitate Philharmonia, a program in León, Mexico modeled on Venezuela’s El Sistema. Mr. Gil-Ordóñez is also a regular guest conductor at the Bowdoin International Music Festival in Maine, and at the Jacobs School of Music in Bloomington (IN) . He has appeared as guest conductor with the American Composers Orchestra, Opera Colorado, Pacific Symphony, Hartford Symphony, Brooklyn Philharmonic, and the Orchestra of St. Luke's, and more recently at the Brevard Music Festival. Abroad, he has been heard with the Munich Philharmonic, the Solistes de Berne, at the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, and the Bellas Artes National Theatre in Mexico City. He worked closely with legendary conductor Sergiu Celibidache in Germany for more than six years, and also studied with Pierre Boulez and Iannis Xenakis in France. The former Associate Conductor of Spain’s National Symphony Orchestra, Gil-Ordóñez received the Royal Order of Queen Isabella, the country’s highest civilian decoration. He has recorded nine albums for Naxos, including PostClassical Ensemble’s three DVDs featuring classic 1930s films with newly recorded soundtracks by Aaron Copland, Silvestre Revueltas, and Virgil Thomson. To learn more about Gil-Ordóñez’ work, visit gilordonez.com

Philip Kennicott is the Pulitzer Prize-winning Senior Art and Architecture Critic of The Washington Post. He is also a two-time Pulitzer finalist (for editorial writing in 2000 and criticism in 2012), a former contributing editor to The New Republic, and a regular contributor to Opera News and Gramophone. His memoir, “Counterpoint: A Memoir of Bach and Mourning,” was published by Norton in 2020. His 2015 essay, “Smuggler” was a finalist for the National Magazine Award and anthologized in that year’s volume of “Best American Essays.” He lives in Washington, D.C.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.