A world without the Ode to Joy would be a bleaker place. No voices in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony? Europe has no unifying anthem. We have no joyful flashmob video, no “Joyful, Joyful” hymn, no explosive Die Hard climax.

Ludwig would never do that to us, right? Guess again. He started writing music to replace the Ode to Joy, and later told friends that he regretted not using it.

Beethoven feared no one appreciated the work’s design, its towering structure, or the high concept holding it all up. And he thought the audience didn’t—perhaps couldn’t—understand the nuances of Friedrich Schiller’s poem well enough to appreciate what he had done with it.

Joy, beautiful spark of divinity, daughter of Elysium!

We enter your sanctuary, Heavenly One, drunk with fire.

Your magic reconnects what fashion has strictly separated.

May all humans become brothers, where your gentle wing rests.

Beethoven thought it was a mistake to leave it in, according to the music historian Mark Evan Bonds, whose bombshell appeared last month in The Beethoven Journal. (Yes, there is such a thing.) According to Carl Czerny, Beethoven’s former star pupil and all-around sidekick, Ludwig told a small group of friends after the premiere that he had made the “wrong choice” with the giant choral movement, and that he planned to replace it with something purely instrumental.

Riiight. Next you’re going to tell me Giacomo Puccini hatched a plan to change La bohème so Mimi survives and Rodolfo dies at the end.

Czerny never wrote about this Beethoven anecdote in his memoirs, but at least three people in their social circle committed it to paper and credited him with the story. One of them was Gustav Nottebohm, a scholar-friend of Brahms, Mendelssohn and Schumann. He was best known for analyzing the sketchbooks where Beethoven captured his raw musical ideas.

One of those sketches comprised nine measures of what Beethoven thought should replace the choral finale to his Ninth Symphony. It’s in D minor—the same key as the symphony. If you’re wondering what it would have sounded like, listen to the finale from his Op. 132 string quartet, which he finished a year later. (Waste not, want not.)

There is a practical reason why Beethoven might have swapped out the Ode to Joy for something without a chorus. The conductor and composer Ignaz von Seyfried, a former student of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, met with Beethoven and Czerny after the Ninth’s first performance. Seyfried was the musical director of Vienna’s historic Theater an der Wien, and conducted the premiere of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio. He was a serious player in Austria’s musical high culture.

Seyfried, the story goes, begged Beethoven during that meeting to scrap the chorus so more performing ensembles could tackle it. A third-tier orchestra might manage its way through Beethoven’s instrumental music, but it’s likely to be in a town where the choir is terrible and the vocal soloists are worse. Make it more accessible, he urged, and more people will hear it.

But Czerny knew that Beethoven, even without his sense of hearing, had a public image as a rock-ribbed force of nature. Nothing good would come of gossip about a deaf maestro second-guessing himself after five standing ovations. Oddly, the fact that Czerny would only discuss this with trusted friends, face to face, gives it the flavor of a closely held secret that has the virtue of being true. If Czerny were making it up for some cynical reason, he would have told a lot more people.

Two centuries later, the smart money is on Beethoven choosing to stick with the Ode to Joy because he genuinely believed in the central message of Schiller’s poem: the universal brotherhood of everyone on earth. There’s evidence that he was a creature of the Enlightenment long before he set the words “Alle Menschen werden Brüder” to music.

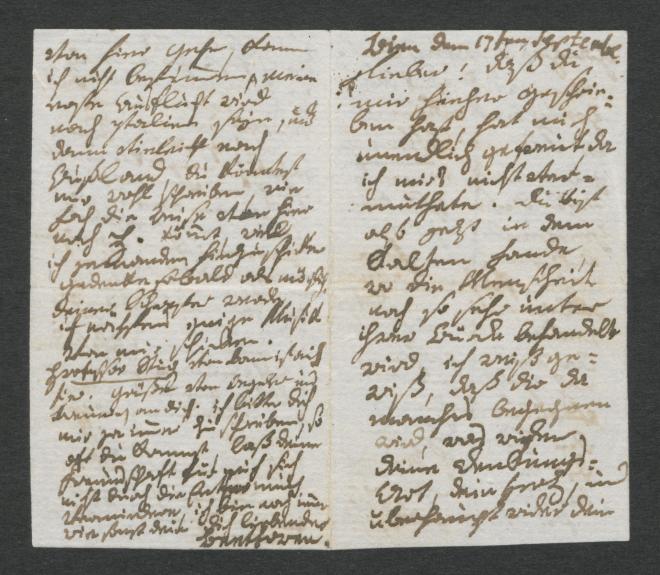

Historians were shocked in 2012 when a Berlin auction house sold a letter Beethoven sent to a drinking buddy from Bonn, a Russian diplomat who had written him in mid-journey to St. Petersburg. No one knew this letter existed. It was big news in academic circles then; and, of course, it continues to be a big deal in The Beethoven Journal.

Beethoven wrote in 1795 to his pal, Heinrich von Struve, that Russia was …

“... a cold land, where humanity is treated so very far beneath its dignity. I am certain that there you will encounter much that goes against your way of thinking, your heart, and against your whole feeling. When will the time finally come when there will only be humans? We will probably see that happy time approaching in only a few places. But, generally, that we shall not see—probably centuries more will pass [before we do].”

When Beethoven writes about a future “when there will only be humans,” he’s not musing about the death of pets, insects, sea creatures and livestock. He’s talking about eliminating “distinctions of rank and class,” according to Julia Ronge. She’s the head curator of the Beethoven-Haus collections in Bonn. Ronge writes that the letter is the best indicator we have of the composer’s “political attitude.”

That paragraph about an egalitarian world is the nut of Schiller’s Ode to Joy, and Beethoven wrote it 12 years before he set the poem’s first stanza to music. He had believed in it for a long time, which makes his cold feet about keeping the choral finale a bit strange. Beethoven may have read the reviews of that first concert, some of which panned the ending. One critic wrote that the final movement “draws the high, sweeping poem down into the depths and mishandles the poetry in an incomprehensible way.” And Beethoven’s chaotic pushing and pulling, speeding and slowing, calm and chaos, were “far more compatible with common drunkenness, than with the spiritual enthusiasm of that Poet’s.”

The quarterly Musical Magazine and Review summed up the mood among Vienna’s sophisticates: Beethoven’s Ninth was so obnoxious that Handel and Mozart might emerge from the grave “to witness and deplore the obstreperous roarings of modern frenzy in their art.”

For cultural wags, this symphonic swansong was a shock to the ears—much like Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring ballet would shock Parisians’ eyes in 1913. We listen to Beethoven with ears that have heard Stravinsky, and Gustav Mahler’s “Symphony of a Thousand,” and Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelung,” and Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder, and the Beatles, and Brian Eno, and Taylor Swift. We can’t imagine how jarring, dissonant and revolutionary it sounded in 1824.

We’ll never know how close Beethoven came to blowing it up, but what if he had replaced the choral finale with a conventional ending? No singing. The symphonic mold remains intact. Would Wagner have seen Beethoven as a giant mile-marker on the road to uniting music, drama, and visual arts? Would we have the “Ring” cycle at all? Would Verdi have maintained his dominance across Europe for a longer time if Wagner hadn’t overshadowed what he was doing?

Would Brahms have completed his first symphony years earlier? He insisted in his late 30s that he would never write one. Brahms was already one of Germany’s most beloved composers, but he wrote to a friend that he was still intimidated, nearly a half-century after Beethoven’s death: “You can’t have any idea what it’s like to always hear such a giant marching behind you!”

Maybe a pacified Ninth, stripped of its vocal power, wouldn’t have become Felix Mendelssohn’s explicit model for his “Lobegesang” symphony. Maybe we never hear Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms. Or Dmitri Shostakovich’s 13th Symphony (the “Babi Yar”). The standard repertoire today includes dozens of multi-movement symphonies with parts for choral singers.

Even Charles Ives put his oar in with two choral symphonies, although I think his main contribution was uniting humanity in grimacing at them.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.