“I want to be able to depict in music a glass of beer so accurately that every listener can tell whether it is a Pilsner or a Kulmbacher.”

– Richard Strauss

Was Strauss that good? He wrote tone poems with elaborate programs that he painstakingly depicts in music, and if you follow every detail of the story while listening you can admire Strauss’s imagination, craftmanship and mastery of orchestration. Even if you don’t follow the program, the music is created with such intentionality that you go along on his journey even if you don’t pick up every reference. The story becomes a framework, like sonata form or a dance suite, which creates coherence out of an inherently abstract art form. Composing a work that successfully tells a specific story while also successfully NOT telling a story, standing on its own as a piece of absolute music, is a challenge that has proven irresistible to composers through the centuries, from Vivaldi to Beethoven to Strauss to John Williams.

But the challenge becomes even greater when a composer uses visual art as his inspiration. Music unfolds over time, while a painting sits there, complete in its frame. Of course, a painting also unfolds over time, as your eye scans the canvas and takes in all the information. You could read the plaque or listen to the audio guide telling you where to look first and what it all means, but if the painting absolutely needed that guidance in order for us to appreciate it, it would be a book and not a painting – just as if Strauss really needed you to know that his tone poem Don Quixote was about ten specific episodes in Cervantes’ novel he would have written a play and not a piece of instrumental music. What painting and instrumental music have in common is that their creators are willing to let their works be open to interpretation by an observer or listener who might not take away the specific experience the author intended. This makes the interplay between visual and aural media intriguing, because the composer of the music is depicting how they see the artwork, adding layers of interpretation and observance.

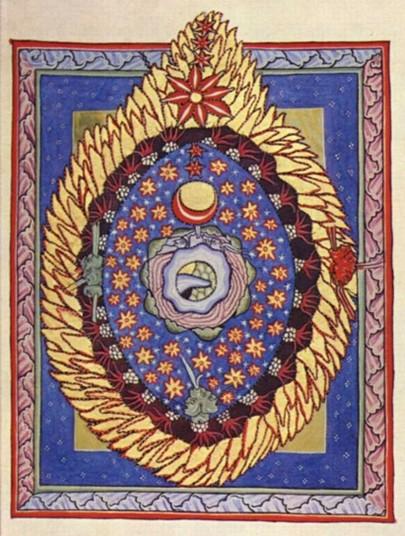

This interplay has been going on a long time. Some of the earliest examples of notated music in the Western tradition appears in illuminated manuscripts – a fancy term for what kids call picture books, illustrated stories. All the way back in 1152 the German abbess Hildegard of Bingen produced Scivias, a volume of pictures, essays, poetry, drama and notated music that were based on her religious visions. The third part of this collection is Ordo Virtutum, a morality play that is the oldest surviving work of musical theater. The relationship between these various elements is not made explicit, but they all work together to create a distinct mood that serves its mystical/theological message. (Pope Eugene III approved of it, impressive at a time when women weren’t allowed to have much of a voice.)

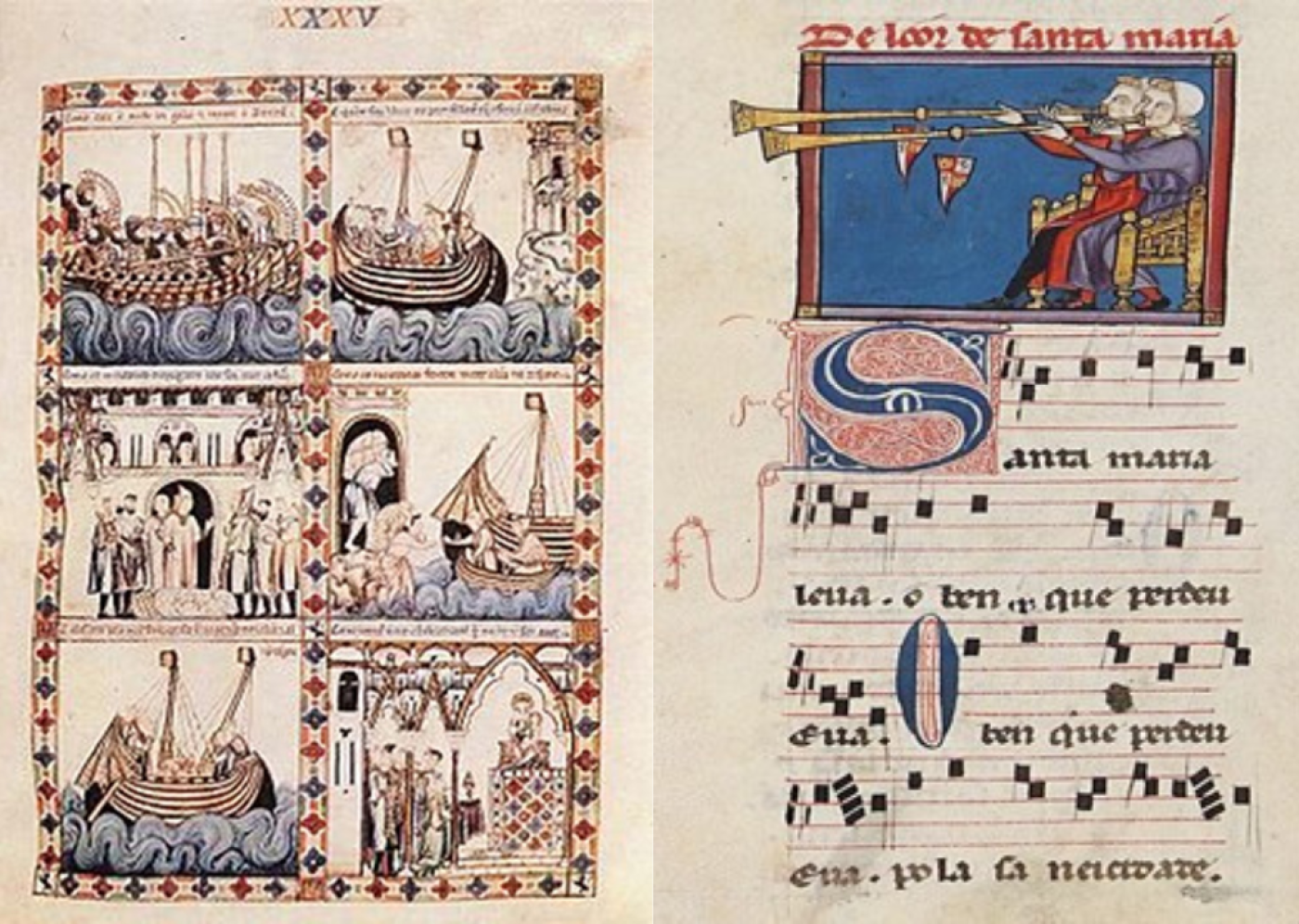

A century later the Cantigas de Santa Maria were produced by Alfonso X of Spain, known as El Sabio (The Wise.) Alfonso produced this collection of mini-miracle plays (featuring the Virgin Mary acting much more like a fickle and earthy Greek or Hindu goddess than the meek and pious Madonna figure) with the help of his multicultural arts council that included Muslims and Sephardic Jews as well as Christians, which you can hear in its complex melismatic melodies. The artwork, words and music work together to create a rich and colorful tapestry that resists categorization.

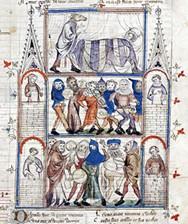

Advancing yet another century (we’re now up to the early 1300s) we have the Roman de Fauvel, a groundbreaking work of allegory/romance/satire that contains 169 pieces of music in a wide variety of styles as well as 78 illustrations. There have been many scholarly debates over how it was performed or staged, but it’s likely that the book itself is the entertainment – you can have a couple of friends over to read the text aloud, play and sing the music, and enjoy the illustrations – that was your evening, the hit DIY Broadway show of Medieval France.

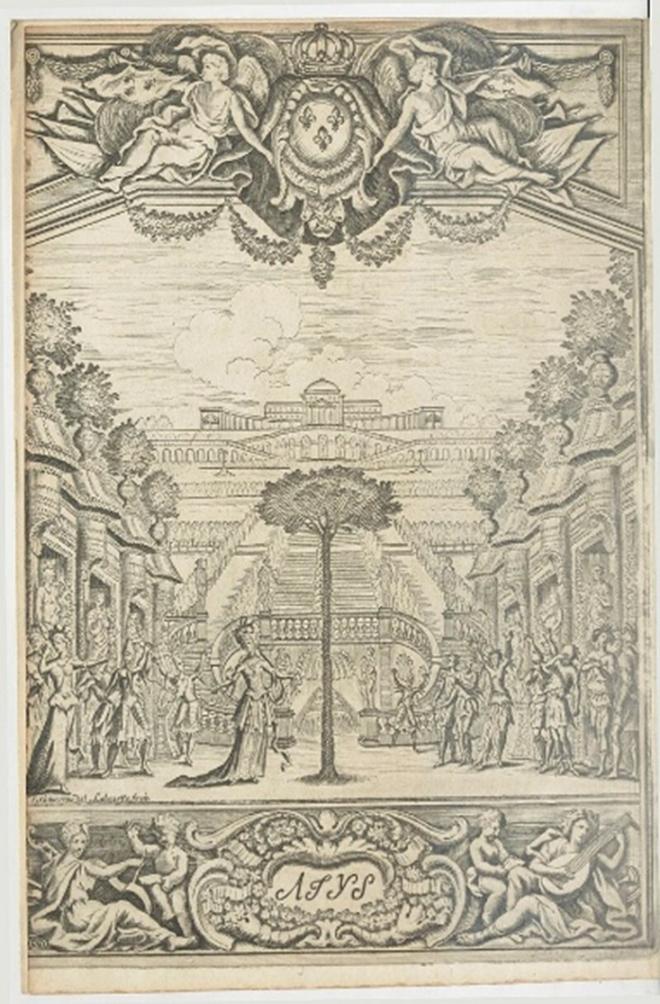

And, in fact, with the rise of opera, composers and set designers had to work together to create the appropriate atmosphere - which, in the case of French Baroque opera, was usually sumptuousness, designs fit for a royal audience (since only royalty could afford to foot the bill for these extravaganzas.) The fact that this depiction of the stage set for Lully’s Atys was printed in the libretto for the opera, published in 1676, indicates that the words, music and visual elements were all of a piece.

Mendelssohn is the very rare example of an artist gifted in both painting and music. Here you see a sketch he made of Edinburgh that seems to inhabit the same world as his “Scottish” symphony.

It was Modest Mussorgsky who produced perhaps the most famous musical collaboration with visual art when he paid tribute to his friend Viktor Hartmann in his piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition. Hartmann was a painter and architect who died at age 38 of an aneurysm. Following his death there was an exhibition of his work in Saint Petersburg, and the experience of walking through the exhibition, remembering his late friend while looking deeply into eleven of his paintings, provided the structure of the suite. This process not only produced Mussorgsky’s most celebrated work, but was also one of the most effective memorials of all time; not only is he responsible for preserving the name of a gifted artist who would otherwise had been forgotten, but is also the only trace left of five of his paintings that have since been lost.

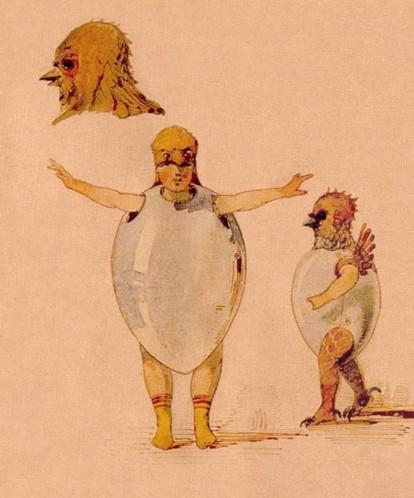

Mussorgsky uses the ingenious device of a Promenade, a theme that represents the composer walking through the exhibit, a noble, angular melody with an irregular metric pulse, depicting the ambling quality of walking through a museum. The first four pictures depicted in musical terms – The Gnome, The Old Castle, Tuileries (Children quarreling in a public garden), and Byldo (Oxen drawing a cart) – have all been lost, so Mussorgsky’s music is all we know of them. The Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks is based on costume designs for a ballet called Trilby choreographed by Petipa, who also conceived and choreographed The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, and we can see from Hartmann’s designs that this inhabits that same fantastical world.

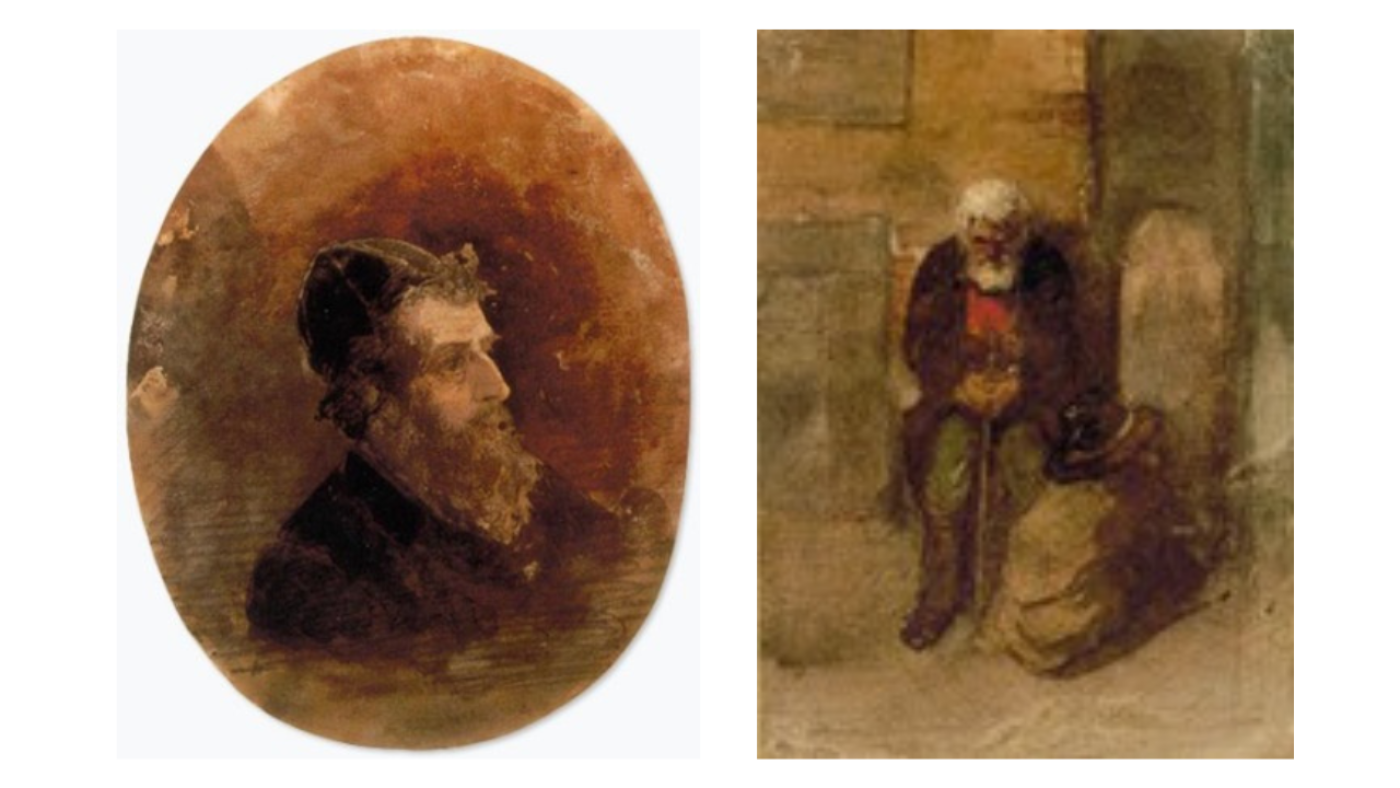

In the next musical “picture” Mussorgsky conflates two paintings that he himself owned, a diptych called “Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle” that the composer described as “Two Polish Jews: Rich and Poor.” There is considerable controversy about this movement, with some claiming that the music is an antisemitic caricature. To my Ashkenazi ears it sounds like a deeply human response to these affecting portraits, depicting their nobility while subtly acknowledging the persecution Jews were being subjected to at that time.

Limoges, another musical portrait of a lost painting, seems like it could be part of a diptych with Tuileries – this time it’s the grown women who are quarreling in a public marketplace.

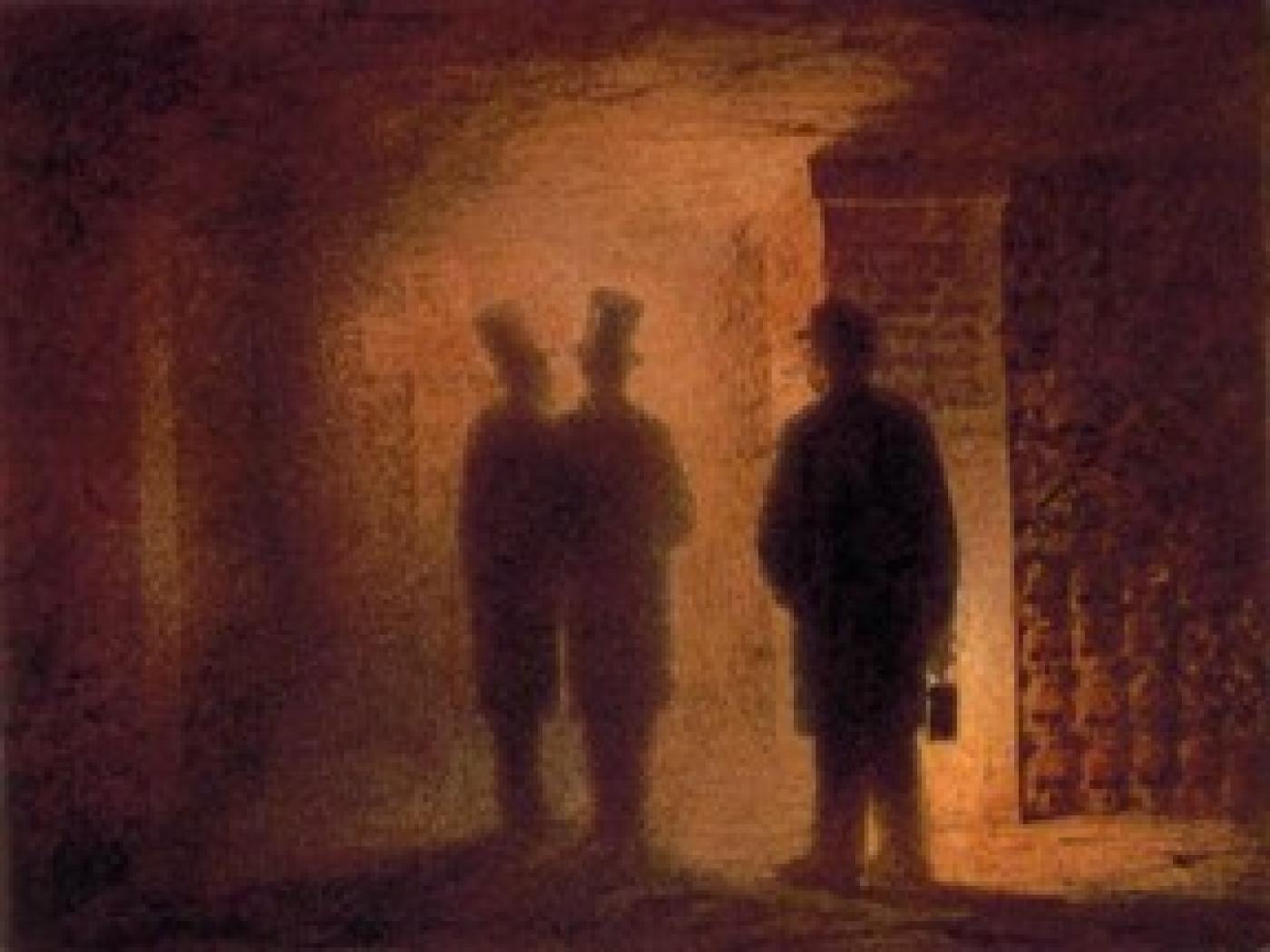

The next picture, the Catacombs, depicts Hartmann himself walking through Paris’s ancient Roman tombs. Mussorgsky uses this image of his friend contemplating death as the basis for the darkest and most personal music in the suite, which also incorporates the Promenade theme as an expression of the composer’s own grief.

The Hut on Hen’s Legs could also form a diptych with the Unhatched Chicks. Both reveal Hartmann to be a kind of early surrealist with a fondness for fowl. Mussorgsky goes into his Night on Bald Mountain mode for a brief but wild ride.

The final section depicts The Great Gate of Kiev, a grand architectural project that was never realized. Hartmann considered it his best work, and while we can be sad both for that unbuilt monument and the other great works we were deprived of due to the shortness of Hartmann’s life, we can hear that promise realized in Mussorgsky’s best work.

Two people who were definitely familiar with Mussorgsky’s Pictures were Claude Debussy and Sergei Rachmaninoff, and one can detect its influence in their musical depictions of two famous artworks. Debussy’s La Mer was inspired by Katsushika Hokusai’s woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa, while Rachmaninoff’s The Isle of the Dead takes us inside Arnold Böcklin’s painting of the same name. Note that these are orchestral works, and the only version of the Mussorgsky that they knew was the original one for piano. I don’t think it’s a stretch to suggest that the chain of influence continued and doubled back on itself when Maurice Ravel orchestrated Mussorgsky’s Pictures, in which one can detect shades of Debussy and Rachmaninoff along with Ravel’s own sense of orchestral color.

Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg, considered the two major composers of the twentieth century, each had special relationships with a major visual artist. The correspondence between Schoenberg and Wassily Kandinsky is as fascinating and important as either man’s creative output. Stravinsky enjoyed a fruitful, playful relationship with Pablo Picasso, and you can hear in Stravinsky’s work a version of musical cubism. But Stravinsky also collaborated with other visual artists. Alexandre Benois and Nicholas Roerich not only designed the sets and costumes for Petrouchka and The Rite of Spring, respectively, but they helped shape the story and structure of those ballets, and many of their design sketches predated Stravinsky’s music and undoubtedly influenced it. His longest work, the English opera The Rake’s Progress, was inspired by a series of eight paintings and engravings by William Hogarth, which he then suggested to W.H. Auden as the basis for his libretto.

So as we see the relationship between music and visual art has a long and fruitful history. Perhaps it might behoove us to try seeing music and listening to paintings; it’s an exercise that would reveal hidden layers in both mediums.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.