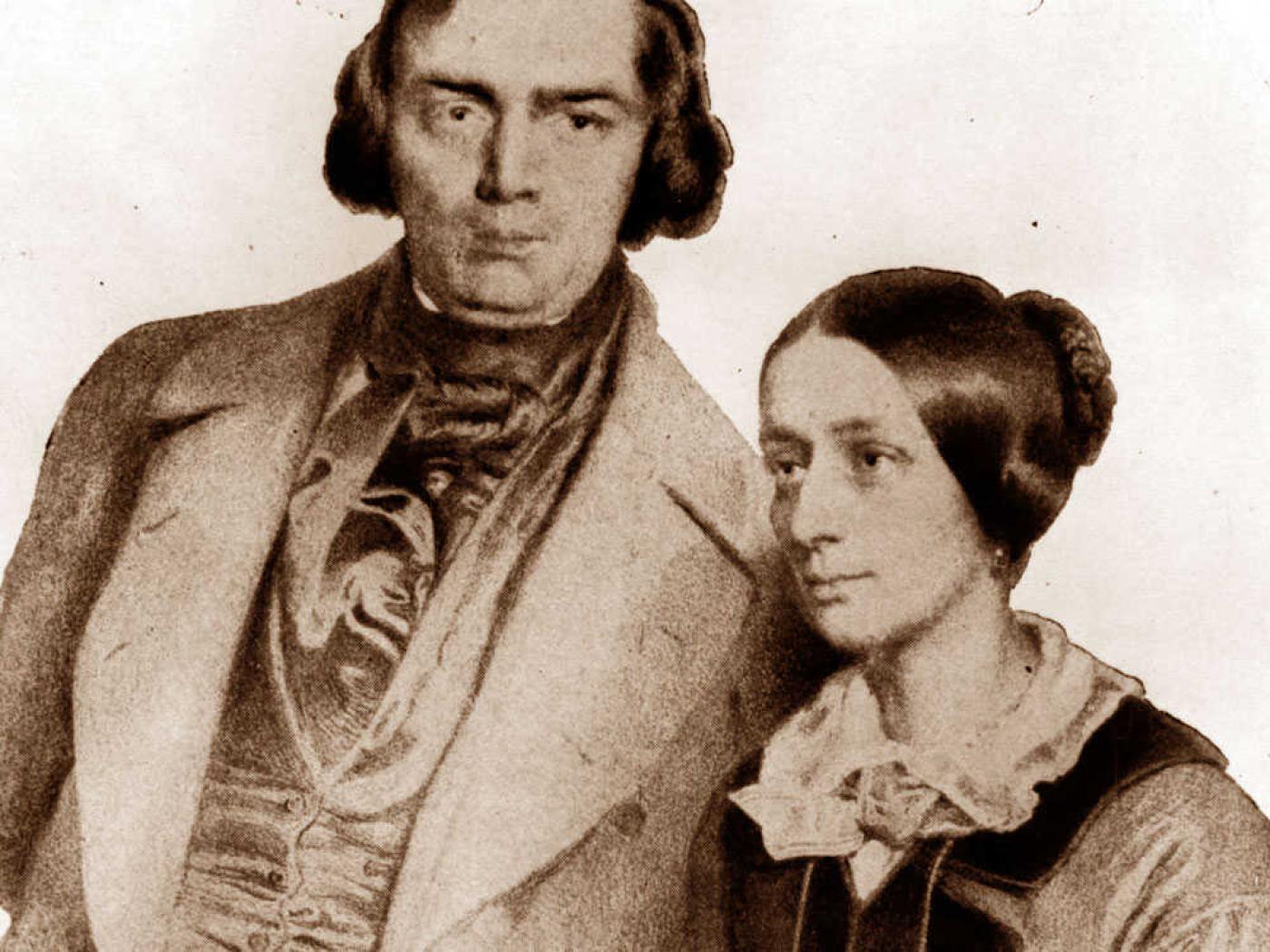

In January of 1839, 19-year-old composer and virtuoso pianist Clara Wieck wrote to her fiancé Robert Schumann: “Dear Robert, don’t take it amiss if I tell you that I’ve been seized by the desire to encourage you to write for orchestra. Your imagination and your spirit are too great for the weak piano.” Yet two years would elapse (during which time Clara and Robert were married, having prevailed in their lawsuit against Clara’s father) before Robert would complete his first orchestral work, his “Spring” Symphony. In the decade that followed, he would compose a robust body of orchestral works, including two more symphonies, the oratorio Das Paradies und die Peri, the Manfred incidental music (the overture to which remains a concert favorite to this day), and his only opera, Genoveva. Toward the end of 1850, he composed the last of his four symphonies, but the third to be published, which we therefore know as his Symphony No. 3.

Not entirely unlike Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony, this work is evocative of a set of experiences. The title “Rhenish Symphony” has stuck: Schumann composed the work after a trip he and Clara took to Cologne. Interestingly, though, the composer ultimately decided to remove any and all descriptive titles to the symphony’s movements at the time of its publication.

The symphony has five movements instead of the more customary four. The solemn fourth movement marvelously elicits an ancestral memory of musical styles from centuries earlier, with lyrical trombones — sounding almost like old sackbuts — that are silent for the first three movements. This symphony has, essentially, two slow movements back-to-back. The original description in the score, “In the character of a procession in a solemn ceremony” is an apparent reference to the September 1850 rite in the cathedral in which the Archbishop of Cologne had been elevated to cardinal. What motivated him to verbally describe the movements initially, such as the second movement’s musical description of the flowing of the Rhine, only to decide to omit such clues? What does the composer want us to take from the experience of hearing this work?

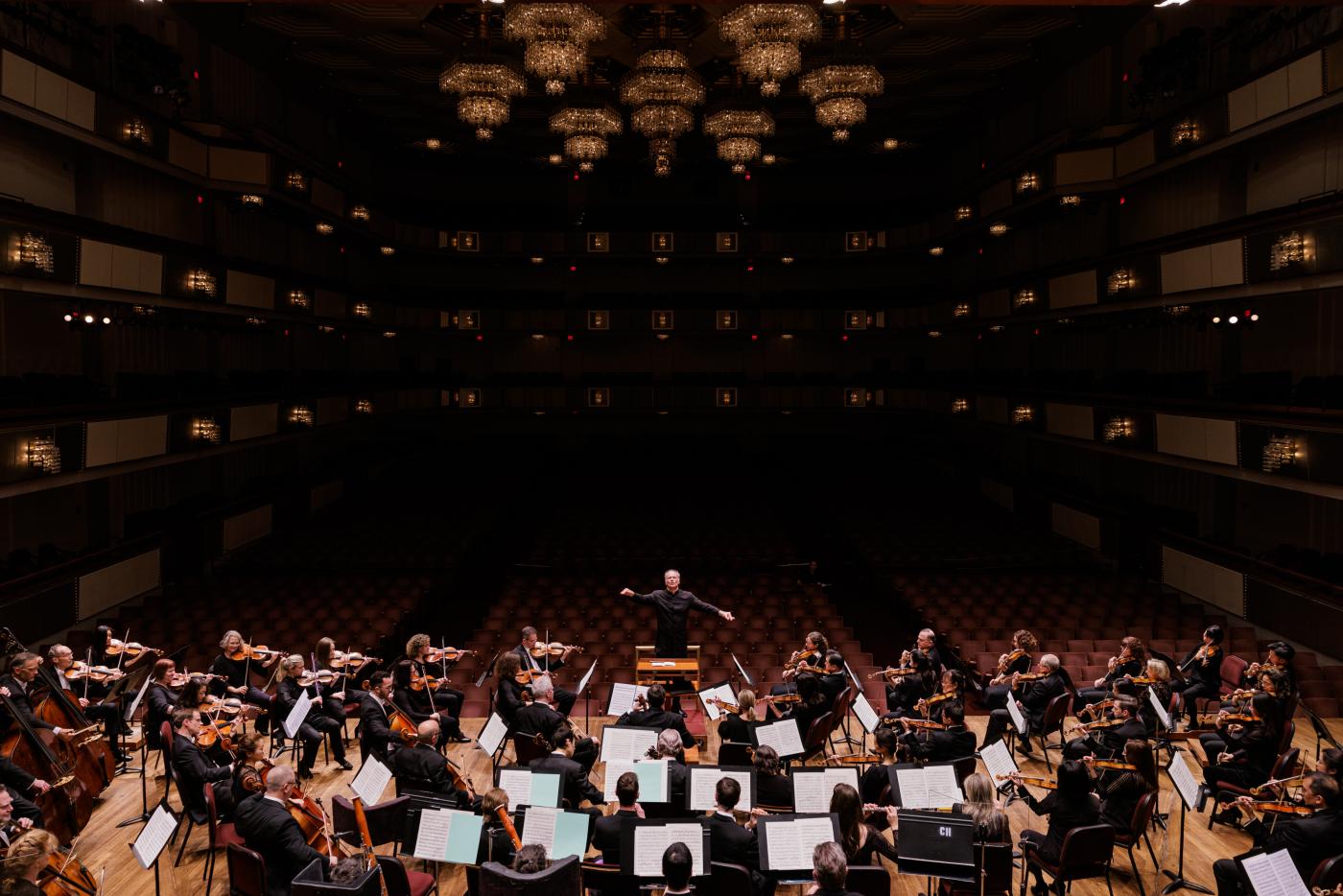

Food for thought for anyone attending the Baltimore Symphony concert at Strathmore on January 5, or the January 12, 13 & 14 National Symphony Orchestra concerts at the Kennedy Center, as both orchestras will be playing this symphony, rightly regarded as one of Schumann’s finest achievements.

Learn more about the life and music of Robert Schumann

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.