WETA Classical's Opera Matinee will present two operas of Richard Wagner in the coming months. First, Die Walküre airs August 30, 2025 in a recorded production from the Royal Ballet and Opera in London. And on March 21, 2026, we broadcast a live production from the Metropolitan Opera of Tristan und Isolde. In this blog, opera scholar Saul Lilienstein and I discuss Die Walküre – the second installment in Wagner’s four-opera Der Ring des Nibelungen cycle -- its attributes, what makes it unique among the other operas in the Ring cycle, and its depth of characters and emotions. We’ve included audio excerpts that illustrate Mr. Lilienstein’s comments. Our previous conversations are available here.

Linda Carducci: Die Walküre is the second in the series of four operas, which Wagner referred to as music dramas, that comprise his grand-scale Ring cycle, an epic series based on Germanic and Norse legends and characters. Underlying the story is a quest to gain control of a magic gold ring that will endow its owner with world power. But it’s also a layered, complex story of human and mythical characters in natural and fantastical settings. Die Walküre steps in a slightly different direction from the remaining Ring operas because its focus is on interpersonal relationships among the characters.

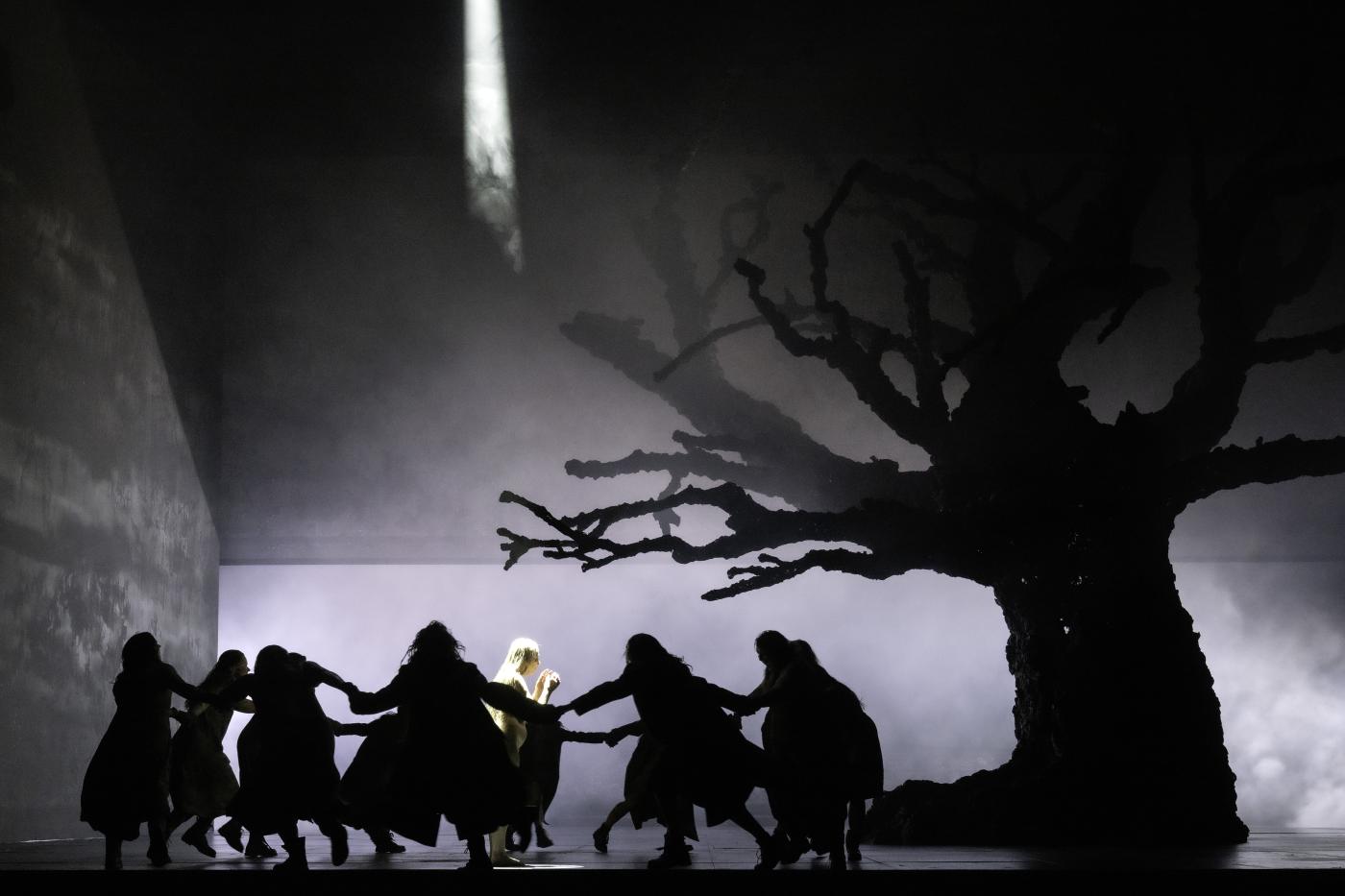

Saul Lilienstein: There is just about every human emotion, including love and what often accompanies love, conflict, between lovers, husband and wife, father and daughter. And like many of Wagner’s other operas, it purposefully unifies elements of music, poetry, drama and visuals into one work of art, what he called Gesamtkunstwerk – “Total Work of Art”. The music is the vehicle to interpret the narrative and emotion of the text.

LC: Die Walküre opens with a more naturalistic, human setting than the first Ring opera, Das Rheingold, which focused on mythical figures like gods, dragons, underworld dwarfs, giants and an earth mother. And Die Walküre introduces characters pivotal to the entire Ring. The first relationship we encounter in this opera is of two strangers who become lovers.

SL: Nature – wind, fire and water – all play their role throughout the entire Ring cycle. Act I opens with a violent storm. Strings tremble in powerful scales, urged forward by the cellos and bass combined.

These are the tones representing the chief god Wotan’s spear and authority, a leitmotif that appeared in Das Rheingold, and it will return throughout the Ring cycle. Here they come again, now with full orchestra, at the height of the tempest.

As we’ll hear, Richard Wagner is a master of musical and emotional transitions. Wotan’s will and his music drives the story forward. It’s the orchestra, not the voices, leading the transitions. We’re going to follow the orchestration through Act 1 to illustrate that. (The vocal writing is very beautiful and expressive – but you’ll be on your own in discovering that.) The orchestral tempest slowly evolves as a young man, Siegmund, on the run from enemies, seeks shelter from the storm in a crude dwelling place. It’s built around a huge tree within the walls and sustaining them. Hear the motif, now accompanying the exhausted man as he stumbles into this rough cabin and collapses on the floor.

In this way, Wotan has brought his hero into the place where a young woman, Sieglinde, lives. She is the slave and wife to a barbarian named Hunding, but right now she is alone with a helpless stranger. But as she comes to his aid, they both are aware of any unknown bond between them.

Siegmund and Sieglinde are unaware that they are really long-ago-separated brother and sister -- twins – the children of Wotan and an earthly mother. Finally, that musical phrase is distilled to the poignant sound of a single cello as the twins gaze at each other in quiet ecstasy.

Although Wotan doesn’t personally appear in the opening Act of Die Walküre, Sieglinde tells Siegmund of a majestic stranger who appeared on the day she was forced into marriage, planting his sword into that sturdy tree, challenging any one of Hunding’s barbarous clan to draw it out. Everything that happens in this Act is through Wotan’s command – the spear that represents his power, the music from his role in Das Rheingold and the winter storm that will bring his children together – to create a family history through them. And that sword – it was Wotan who embedded it there, waiting for the arrival of the young man destined to possess it. Act 1 ends in an erotic victory as Siegmund brandishes that weapon and he embraces Sieglinde, his sister, his bride, as his own. It’s too late for them to turn back now. They are overcome by physical passion. Winter is past. Spring has come onto that stage and into their lives.

LC: For all of the mythical elements and superhuman quests in the Ring cycle, it is the human stories within Die Walküre that makes it so relatable and appealing. This opening scene is an example. And the music underpinning the awakening of Siegmund and Sieglinde to recognition and unstoppable passion is masterful.

SL: The prelude to Act 2 is an orchestral description of the desperate lovers on the run, for Hunding is after them, filled with murderous intent.

We know it was the hidden presence of Wotan behind the drama of Act 1, but he has created an insurmountable problem for himself, and when we meet his wife, Fricka, up there in Valhalla, she won’t let him off the hook. Fricka is the goddess of family, marriage and morality. There are rules in this Universe. It was Wotan himself who put them there. Fricka demands that the twins be punished for committing incest and adultery, and she belittles Wotan’s specious argument that the human couple he created acted of their own free will. The hypocrisy of his position is evident. Wotan’s music will return but accompanies Fricka’s voice, not his. Hear it weaken and stumble into pitiful fragments for Wotan. No love is lost between these two. Fricka has won, and despite Wotan’s love for his son, he acquiesces: “No more protection for Siegmund.”

He orders the Valkyrie Brünnhilde (his child from a different marriage, don’t ask . . . ) to tell Siegmund that he must die and go to Valhalla, but he must leave Sieglinde behind, for Valhalla is the great hall where dead soldiers alone find honor.

LC: That brings us to my favorite scene in Die Walküre, when Brünnhilde must tell Siegmund of Wotan’s portentous decree, even though she observes the lovers with compassion.

SL: I feel the same way about this moment. Let’s take some time with it. First, some background: The music we hear is a new leitmotif, hers, derived from Beethoven’s last composition, the String Quartet Op. 135. Beethoven had given a title to the final movement: “The Difficult Decision” and words to its main theme: “Must it be?” (In German: “Muss es sein?”). You’ll hear in this short excerpt how much insistent power he gives to it, with cello and viola playing it together.

At this moment in Die Walküre that thought, “Muss es sein?”, is transformed into Brünnhilde’s sorrow at the task ahead. Wagner’s music becomes solemn and spare, and in a minor tonality, made all the more affecting by his orchestration. A quintet of lower brass instruments play the theme pianissimo along with the gentle pulsing of tympani.

LC: It sounds to me like a softly beating heart at a tender moment when a man is told that he must die.

SL: Her inner wish is “must it be?” -- but when Brünnhilde addresses Siegmund the orchestration becomes richer, turning away from minor keys and into the major.

Brünnhilde sings with the serene authority of Valhalla surrounding her.

Linda, there is a proverb of unknown origin which states, “If you are going to steal, steal good.” Wagner stole well, don’t you think?

LC: For sure, and to Wagner’s credit, he’s acknowledging the greatness of Beethoven. This transformation of Beethoven’s string quartet, which contemplates mortality and the force of destiny, overshadows this poignant scene from Die Walküre in much the same way.

SL: OK, Siegmund refuses to go to Valhalla and leave Sieglinde. Brünnhilde – and we – are moved by his love. He is certain that the sword Wotan had provided will protect him from harm. Brünnhilde is deeply affected by Siegmund’s devotion. For the first time, she has discovered a power unknown in Valhalla: the depth of human love. So she defies Wotan’s order and decides to let Siegmund survive his battle with Hunding. In one sublime moment of calm, Siegmund cradles his sleeping sister, hoping that she may slumber on while his fight to the death if fought and won.

Bu this is not to be. An angry Wotan intercedes as Siegmund and Hunding struggle; he allows Siegmund to die and then kills Hunding in disgust. Brünnhilde escapes with Sieglinde and the remnants of Wotan’s sword. The great god is furious and he follows in hot pursuit of his disobedient daughter.

LC: Brünnhilde’s act of defiance leads to the final Act (3) and the final relationship of the opera, that of father and daughter.

SL: The prelude depicts Wotan’s fearsome power. This is the famous “Ride of the Walkyries”, and the music is so well known that we may be forgiven to taking it for granted. But Wagner’s choices – those demonic trills in the woodwinds, the strings leaping in a mad gallop – and then the horns enter with . . . well, it’s a state-of-the-art display of orchestral imagination.

Wotan must punish Brünnhilde for disobeying him. Yet before he caroms onto the stage in anger there is a significant scene between Brünnhilde and Sieglinde. Sieglinde seeks death rather than live without her lover, Siegmund. But Brünnhilde consoles her, telling her that she is pregnant by Siegmund and now must live for their child, who will be named Siegfried.

Sieglinde responds with a cry of ecstasy in gratitude to Brünnhilde: it’s a new phrase that must have come to Wagner in a blinding flash. The theme is only a few seconds long and we won’t hear it again until the last moments of Götterdämmerung.

LC: Now we are left with two people – Wotan and his daughter, Brünnhilde. It’s in this final scene where we experience depths of anger, anguish and love, emotions that these gods share with humans. Tell us more about Wagner’s music that supports this heartrending interaction.

SL: Enter Wotan, infuriated by Brünnhilde’s disobedience. Even though Wotan is portrayed as a powerful and decisive god, his love for Brünnhilde is right here in his music.

Yes, this is a stern father, yet anguished at having to punish his child.

Brünnhilde pleads forgiveness, explaining that she knew that Siegmund was Wotan’s son and his chosen hero, and her defiance was an act of love. This opera began with a winter’s storm transformed into the softness of Spring. Now Brünnhilde’s music, in her voice and in the woodwinds, is a lyrical transformation of those same stern descending scale passages which defined the god.

And what will be her future? Her punishment will be a loss of her divine status, put to sleep and only to be awakened as a mortal woman. Wagner’s chromatic harmonies move from woodwinds to strings in a beautiful sonic representation of how this woman will fall into enchanted slumber.

Brünnhilde pleads with passion for a protection by a fire that only a heroic man would dare to breach.

Wotan is overwhelmed with love. Their bond grows stronger in the realization that they will never see each other again. Beyond all words, they embrace and are embraced by a magnificent orchestral voice.

Wotan sings farewell to his beloved daughter in tones of unsurpassed lyricism and compassion.

“Zum letzten Mal” (‘For the last time, I kiss you farewell.’) Wagner spoke of these moments as the saddest music he ever wrote.

Finally, he creates a magic fire that encircles and protects Brünnhilde. The orchestration for dancing woodwinds led by piccolos and flutes accompanied by string arpeggios is one of upmost enchantment.

His task is complete, but Wotan is heartbroken. Theirs is a father-daughter relationship as touching as anything in Wagner, similar to ones we find in some of Verdi’s operas. With its focus on the complexity of human relationships layered with love, passion, conflict, anger and parental affection, it is no surprise that Die Walküre is the most often performed single opera from the Ring cycle.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.