On Sunday, June 11 at the Kennedy Center, Dr. André J. Thomas will conduct the Choral Arts Society of Washington in a concert featuring music by two living American composers, Dominick DiOrio and Adolphus Hailstork, and a celebrated Mass setting by Joseph Haydn, the Missa in angustiis, also known as the “Lord Nelson Mass”.

New York state native Adolphus Hailstork III was born in 1941. His composition teachers include Nadia Boulanger and David Diamond; his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees are from the Manhattan School of Music, and he has a doctorate in composition from Michigan State. Hailstork’s 1989 cantata I Will Lift Up Mine Eyes draws its texts from the Psalms. It is dedicated to the memory of pianist, composer and educator Undine Smith Moore (1904-1989), a Fisk University alumna who went on to teach at numerous American colleges, universities and conservatories; being co-founder of the Black Music Center at Virginia State College was one of her many distinctions. Hailstork’s cantata is in three movements, and a tenor soloist figures prominently alongside the choir and orchestra.

Dominick DiOrio teaches at Indiana University, and is a guest chorus master for this Choral Arts performance. He has a doctorate in conducting from the Yale School of Music and is currently Artistic Director of the Mendelssohn Chorus of Philadelphia, now in its 149th season. DiOrio’s SOLARIS, completed in 2017, is a choral symphony in three movements that sets texts by Meghan Guidry, Megan Levad and Misha Penton.

Many of Haydn’s works have nicknames, quite a few of which are the products of others’ imaginations, but the title Missa in angustiis (“Mass for troubled times”) is the composer’s own. It is the third of the final half-dozen settings of the Mass Ordinary he was to set; all six of them, composed between 1796 and 1802, were for the name-day of Princess Marie Hermengild Esterházy, in service to whose family Haydn spent much of his adult life. (Beethoven’s 1807 Mass in C, incidentally, was also composed for the same Princess’s name-day; Beethoven admitted to her princely husband beforehand that “I will hand the Mass over to you with great trepidation, as Your Serene Highness is accustomed to having the inimitable masterworks of the great Haydn performed.”)

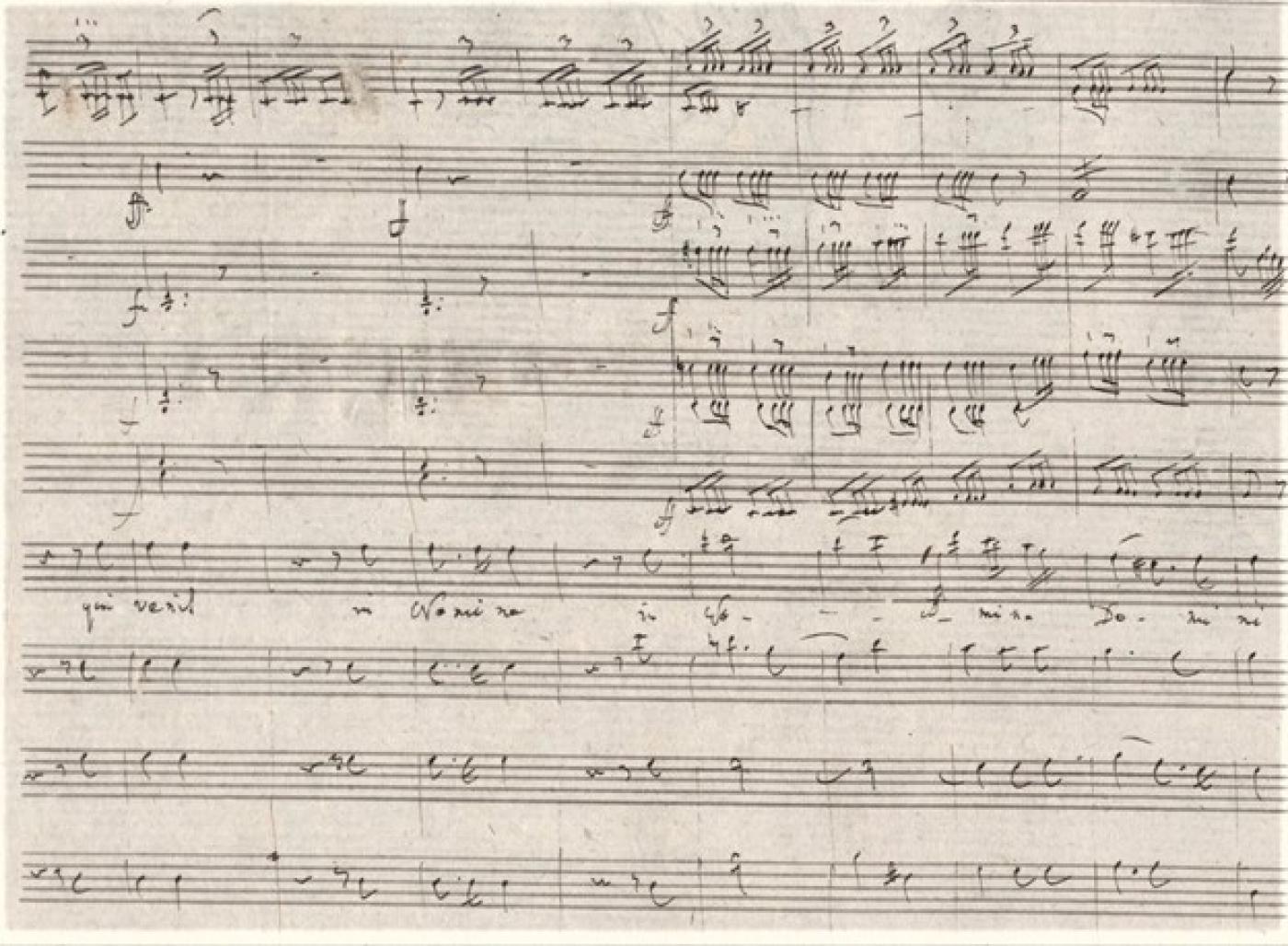

The Missa in angustiis, composed and first performed in 1798, is scored for strings, organ and timpani, and no wind instruments other than three trumpets: Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II had dismissed the “Grenadiers’ band” of woodwind players from his service earlier that same year. (Some editions of the score include woodwinds, though whether Haydn himself sanctioned this is an unanswered question.) An organ was nothing unusual in the instrumentation of liturgical music at any time in the eighteenth century, but an exceptional (though, certainly in Haydn’s Masses, not unprecedented) feature of the Missa in angustiis is an organ part which is written out, rather than merely providing continuo harmonization; this is especially memorable in the “Qui tollis” of the Gloria, with its equally remarkable writing for the solo bass voice.

The “troubled times” of the Mass’s title resound in the dramatic D minor sweep of the Kyrie, and especially in the Benedictus, with its martial trumpets and timpani, perhaps echoing the encroaching threat of Napoleon’s imperial ambitions.

In Austria at that time, deep anxieties about war were not misplaced: Haydn would spend the last weeks of his life in Vienna in the spring of 1809 rattled by the sound of French artillery in the city. The nickname this Mass setting acquired, however, is linked to something of a respite in Austria’s struggle against the haughty Corsican: in August of 1798, less than two months before the first performance of the Missa in angustiis, Napoleon was dealt a decisive defeat at the Battle of the Nile, when British Rear Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson led his fleet to victory against the French off the coast of Egypt. Thereafter the nickname “Lord Nelson Mass” stuck.

Despite the circumstances, this work is by no means without the ebullience that characterizes so much of Papa Haydn’s choral writing: leave it to him to open the Credo with a strict canon at the fifth — one of the most cerebral, academic compositional techniques — and turn it into a joyous and confidently optimistic affirmation of faith.

Lord Nelson himself would pay a call to the Esterházys two years later: he and Haydn certainly met at that time, and it is even possible that the choral masterpiece nicknamed for the triumphant admiral was performed in his hearing, led by its composer at a time when both men were at the height of their renown.

Learn more about the life and music of Haydn

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.