The tradition of Western Classical Music goes back a very long time; and when you listen to pieces written during historical periods that are very far apart from each other, you might well wonder why in the world these very different sounds and musical structures still belong in the same genre. Part of the answer is the same as with any living cultural practice whose roots go back centuries: the actual details and substance of the practice can often evolve radically, while still being called the same name. Just imagine having a conversation in English with one of the characters in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Technically, you’d both be speaking English, but you’d have a very hard time understanding each other’s language.

Nonetheless, the joys of Chaucer’s poetry are still in principle available to us today, especially if we have some help, for example from a pronunciation and glossary guide to Chaucer’s version of English, which today we call Middle English. So too with music: a guide to the different historical styles and aesthetic aims that Classical Music has gone through over the course of the last 1500 years, can help us appreciate the sense for wildly different kinds of musical beauty that we can still share with people of the distant past.

Medieval Period: 500AD – 1400AD

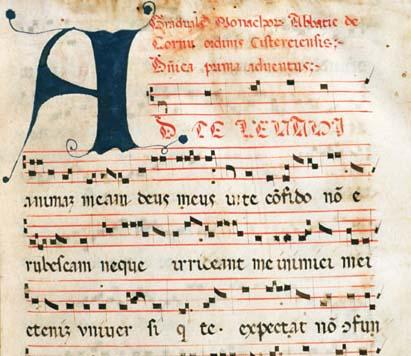

If you thought music from the 1700s is going back a long time, try going even farther back by over a thousand years! That’s where we find the roots of the Classical Music tradition; and the most important context for those roots was the only institution spread across Europe that was keeping the practices of scholarship and writing alive (albeit in religiously dogmatic ways at times), in the wake of the collapse of the western Roman Empire: the church. This context gave us two hugely important elements of Classical Music: 1) the body of hymn songs known as Plainchant, which served as melodic building blocks for composers to riff on and experiment with for many centuries to come, and 2) the invention of music notation, which made possible the idea of a melodic tapestry: multiple different melodies that are meant to be sung all at the same time. Experiments with this idea, technically known as ‘polyphony,’ got very complex indeed over the centuries, and composers’ aesthetic preferences for harmonies back then were quite different from ours, so the resulting chords and sonorities can take a while for us modern listeners to get used to, but once you do, the beauty of the tapestry is undeniable.

The singing of Plainchant continues in monastic practices to this day, and many recordings of monks performing these Anonymous compositions are out there for us modern listeners. The earliest composer whose name we know was also one of the greatest composers of the whole Medieval period: Hildegard von Bingen. In listening to her music, you’ll want to imagine yourself inside a big, echoey, stone church building, contemplating the wonders of God’s creation. For an entry into the incredibly complex melodic tapestries of the later Medieval period, check out the music of Leonin, Perotin, and Guillaume de Machaut. Machaut is particularly important because he was also prolific in writing poetry and music in secular contexts, and he imported all that complexity from the polyphonic church music styles, into his very secular love songs.

Renaissance Period: 1400 – 1600

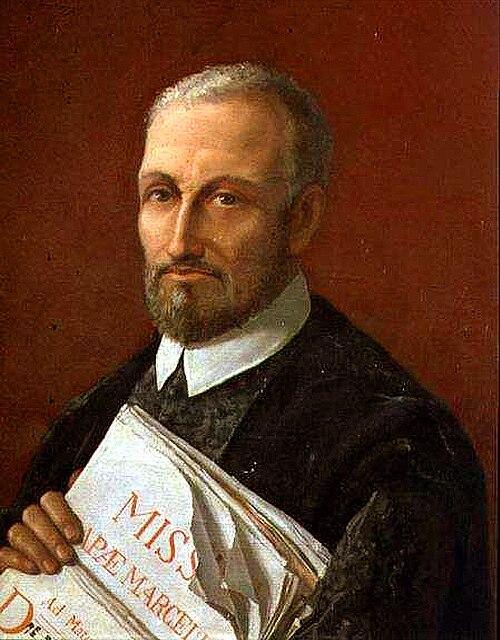

Musical styles in the Renaissance were marked by two trends. First, musicians in the secular world started getting in on the polyphonic action by creating a parallel repertoire of popular songs that used many of those same Medieval techniques of melodic tapestry. Second, the church higher-ups started getting fed up with what they saw as too much musical complexity coming from their employees’ compositions. For the more austere church authorities, the music they commissioned was supposed to be an aid to spiritual contemplation; if the music has too much intricate stuff going on, it’s just going to distract from the religious words that we’re all supposed to be contemplating here! So in order to preserve the musical beauty of polyphonic singing while complying with their bosses’ demands, church composers developed a way of making musical tapestries that maximized the smooth, meditative flow of melodies, while ensuring that the words could still just about be understood by the listener.

Thus, Renaissance music gives us sonorities that we modern people often associate with church choir music. Its biggest aesthetic ideal was to evoke a sense of angels endlessly singing the music of the spheres. Over in the secular music world, instruments were finally starting to get in on the polyphonic fun as well, especially instruments that allowed a single performer to play polyphonically, like organs, harpsichords, and lutes. For secular song forms of the time (such as the madrigal), composers had more freedom to use dance rhythms in their melodic tapestries, but since the words were still what would make a song popular, they made sure the music’s intricacy would not get in the way of the listener’s ability to understand those words of love poetry either.

For the early, almost medieval-sounding Renaissance music which got the church authorities so vexed, be sure to check out the music of Johannes Ockeghem and Guillaume Dufay. For a great entry into the music of the spheres which followed, check out Josquin des Prez, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Orlando di Lasso. And for the greatest English lute songs in the madrigal spirit, you can’t do better than the music of John Dowland.

Baroque Period: 1600 – 1750

In the year 1600, the most momentous musical invention in Classical Music came into the world when a prestigious social network of artists and philosophers in Florence created Opera. Combining theatrical spectacle with the emotional power of solo singers accompanied by the kaleidoscopic musical colors of a whole orchestra, this new thing called opera became the most popular multi-media entertainment vehicle all over Europe in very short order. Besides the many musical possibilities and necessities entailed by opera, it created a great social and financial incentive for wealthy courts and cities to form standing orchestras and for composers to write music that exploit the orchestra’s vast sonic potentialities in all sorts of musical contexts. Even church music eventually started borrowing techniques from the opera house to present sacred music dramas in weekly worship services.

The Baroque’s aesthetic ideal was music as an emotional illustration of theatrical drama; so each song, whether vocal or instrumental, is seeking to distil the strongest emotions felt by a protagonist in the spotlight of an imagined theatrical scene. Thus, the Baroque saw a return of great melodic complexity, and added to it a powerful role for the accompanying instruments: a harmonic complexity made possible by new instrument technology and science of the time.

For a taste of how the transition from Renaissance to Baroque styles sounded, seek out the music of the greatest genius whose career spanned that transition: Claudio Monteverdi. In purely instrumental music, Arcangelo Corelli’s violin music created the foundations of Classical Music’s melodic language for the Baroque and into the next several centuries. The culmination of the Baroque style’s evolution is encompassed by the music of the four greatest composers of the late Baroque: Georg Philip Telemann, Domenico Scarlatti, George Frideric Handel, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

Classical Period: 1750 – 1820

This period coincided with big and quickly modernizing developments in Europe’s economies and political setups (not least of which was the inspiration from the American Revolution. The effect these developments had on musicians and musical style was a strong incentive from a burgeoning middle class for composers to write music that was straightforwardly tuneful (no more of these aristocratic frills and fripperies for us regular folk), and whose architecture was crystal clear, well proportioned, always in good taste. It’s an aesthetic ideal that people of the time associated with art and architecture of the ancient Greek and Roman worlds (the Classical era of Western history), so that’s why we call this era in music the Classical Style. Its three greatest exponents should be very familiar to listeners of WETA Classical radio: Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. But for a taste of the Classical Style’s origins, the music that Haydn and Mozart were raised on, make sure to check out the music of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (especially his keyboard sonatas), Georg Chrstoff Wagenseil, and Francois-Joseph Gossec.

Romantic Period: 1820 – 1900

By now, you may have noticed a trend in the stylistic developments from one period to the next, wherein the aesthetic ideals of one period will tend to be cast in reaction to the previous period’s excesses either in the direction of complexity or simplicity. It’s a common pattern in human cultural evolution, and it continues in music to this day. Romantic composers sought to embody the full depth and scope of human subjectivity, which, as Walt Whitman famously pointed out, contains multitudes. To describe those multitudes in the greatest detail possible, composers had to invent a huge array of harmonic, structural, and sound color tools for their music, while also expanding the subject matter that music might address itself to. From literature to philosophy, to visual arts and politics, the Romantic Period declared that music could communicate ideas about all those domains of human life and society. The literary aspirations of early romanticism are most beautifully captured by the songs of Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann. Frederic Chopin gave the era a new poetry of the piano, which remains the bedrock of modern piano playing to this day. Classical Music also started to get more and more nationalistic in the Romantic Period, so composers often categorized themselves according to their nationalities. For the highest German romanticism, listen to music of Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner; enjoy the French joie de vivre with Hector Berlioz and Gabriel Faure; Italians were all about opera with Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, and Giuseppe Verdi; Edvard Grieg and Jean Sibelius give us powerful Scandinavian landscapes; go to Modest Mussorgsky and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky for the Russian romantic grandeur; Bedrich Smetana and Antonin Dvorak revel in souped up versions of Czech dance and song; and check out music of Edward Elgar and Amy Beach for the best in Anglo-American sentimentality and ingenuity.

Modern Period: 1900 – Today

The modern period has seen and continues to see ever increasing acceleration of technological and social changes ever since the start of the 20th century. Classical Music has been a particularly poignant mirror of all those changes: at times disturbing, bewildering, or only very weirdly beautiful. New musical styles, substyles, and aesthetic ideals have proliferated exponentially, which opens so many exciting new possibilities, as well as opportunities to celebrate previously marginalized voices and perspectives, and the Modern period is now able to welcome them all into the Classical Music tradition. The early Modern period was spearheaded by the wild and wonderful experiments of Claude Debussy, Igor Stravinsky, and Arnold Schoenberg. Their music remains a mind-expanding invitation to develop a flexible and capacious sense for the myriad ways in which music can be beautiful. The music of Aaron Copland, Benjamin Britten, and Paul Hindemith embraced this capaciousness as well, even while often mixing it with more straightforwardly pleasant sonorities. In our own century, it’s impossible to tell what music will ultimately end up standing the greatest tests of time, but some of my favorite 21st-century composers are: Joan Tower, Missy Mazzoli, Reena Esmail, and Gabriela Lena Frank.

I hope you enjoy finding new musical time travel options from this not-as-long-as-it-could-have-been Guide to Classical Music’s historical periods. Happy listening!

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.