Europeans looked at the American Revolution with fascination and perhaps some envy. Over in the New World, it seemed, they get it. They’re putting their bodies on the line for concepts like universal brotherhood and freedom of thought instead of just singing about them in Masonic lodges and publishing philosophical pamphlets like Voltaire’s and Rousseau’s that rarely reached their intended audience (though they were appreciated by some of the Founding Fathers.) The American Revolution helped spur deep longings among Europeans, including inspiring the French to try their own version.

In July 1776, while the United States was finally born out of years of intense violence and yearning, the 20-year-old Mozart was hard at work on what turned out to be the longest purely instrumental work he would ever compose, the Haffner Serenade - which, truth be told, was hardly a revolutionary statement. Its hour-long length of eight movements (including a mini-violin concerto) plus a march that preceded and followed the work played while the musicians literally marched on and off the outdoor stage (he wrote it so that it could be performed without cellos - he later incorporated them for indoor stationary performances of the piece - but the unhappy double bass players had to strap their instruments to themselves so they could play while walking) was all due to its use as music for a wedding involving one of Salzburg’s most prominent families. While an important work in Mozart’s musical development, it contains nothing to challenge its function as entertainment and festive and pleasant ambience. But as we will soon see, Mozart wrote another serenade a few years later that did all of that and more, a product of a brewing cultural movement inspired by the revolutionary movement that led to the most famous event of July 1776.

A particular type of musical restlessness had been in the air for a couple of decades with a pensiveness that stood out in this age of decorative rococo stylings. In the 1750s Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and his employer Frederick the Great, a composer in his own right, created anxiety-ridden music in minor keys that was edgy while adhering to the bounds of harmonic decorum. In the 1760s Christoph Willibald Gluck wrote the groundbreaking ballet Don Juan; its furious d minor finale depicting the protagonist descending to Hell was clearly on Mozart’s mind when he wrote the finale to Don Giovanni a quarter century later. Mozart himself wrote his well-known “little g minor” symphony, no. 25, in 1773, perhaps the best work by a 17-year-old that accurately expresses teenage angst as it was being experienced. His friend and mentor Joseph Haydn’s symphonies started to take a moodier turn in the late 1760s; in 1772 he wrote two minor key symphonies that are among his greatest, no. 44 (subtitled “Mourning”) and 45, the famous “Farewell” symphony, which, in tune with the revolutionary spirit, was also an important instance of labor activism, in which the musicians walked off stage at the end, one by one, to signal to their employer that it was well past time to leave the summer palace so they could go back home to their families.

Joseph Vernet, A Shipwreck in Stormy Seas (1773), National Gallery, London

A similar restless mood could be found in other art forms as well. Stormy weather became a favorite subject of German artists of the period. Writers like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe produced works that celebrated the spirit of rebellion and nonconformity like Prometheus (1772) and The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). And it was a childhood friend of Goethe’s, a German playwright named Friedrich Maximilian von Klinger, who unwittingly gave a name to this cultural phenomenon and defined it as a movement.

In the fall of 1776, Klinger wrote a play about a group of Europeans (country undetermined), led by a man with the rather on-the-nose name of Wild, who sail to America (colony undetermined) and check into an inn where the entire play takes place. Wild made this journey with the intention to fight alongside the colonists, but after fighting a duel with an old nemesis that results in minor injuries, he falls in love with his co-combatant’s sister and gets married instead. It’s unclear whether it was meant to be an actual statement about the revolution or a satire on the nature of its claim in the European imagination; contemporary reviewers couldn’t figure that out either, and the play was not a success. It would surely be forgotten entirely were it not for its title: Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress). The title caught on as a catchphrase for this German cultural movement that, as it turns out, was nearly over, at least in the literary sphere, though it would continue to resonate in music.

Perhaps one telling sign of its impact is in another serenade by Mozart, composed six years later in 1782. Despite its apparent function as a piece of pleasant ambient music to be played at night on the streets of Vienna by a wind octet, the serenade in c minor, K. 388, is unusually dramatic and has the structure and depth of a symphony; one can only imagine the reaction of people out for their post-dinner walk to this intense music. In another six years Mozart would produce his later g minor symphony, no. 40, in which he transformed the Sturm und Drang style from performative angst to a profound statement, a pinnacle of the art form. Beethoven studied this piece intensely and it influenced his own work, so it’s not a stretch to claim that he continued the Sturm and Drang movement into the early 19th century with works like the Appassionata Sonata and the Fifth Symphony. And in his final symphony, he includes a setting of the final great literary work of the Sturm und Drang, a poem by Friedrich Schiller called Ode to Joy, which put a definitive period at the end of the movement.

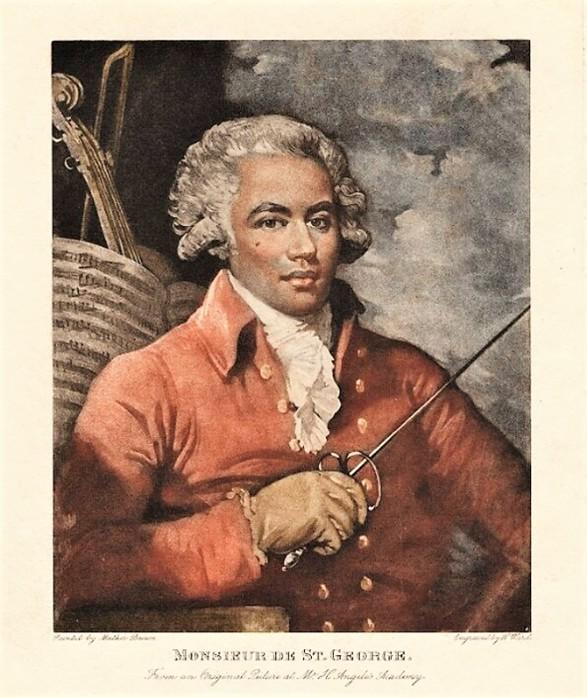

In France, however, the movement was not just a passing fad of earnest utterances by passionate men who thought that passion itself was revolutionary. They were attempting to make real progress in substantial gestures, not all of which were successful. Back to that pivotal year of 1776: the newly crowned Louis XVI approves of the appointment of Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges to direct the Paris Opera. The son of a Creole slave and her owner, born in the West Indies and now taking Paris by storm with his tremendous multiple talents (composing, violin playing, conducting, fencing), Saint-Georges soon had his authority challenged by three of the Opera’s leading ladies, who refused to “submit to the orders of a mulatto.” The king responded by taking back control of the Opera from the city and reassigning Saint-George to the position of private musician to Marie Antoinette. While his career was salvaged and Louis got to assert himself (the king was only 21 at this time), the fundamental problem of racism in high places went unchallenged. (Louis had 17 more years of trying and often failing to find adequate political solutions to various scandals before he was guillotined.)

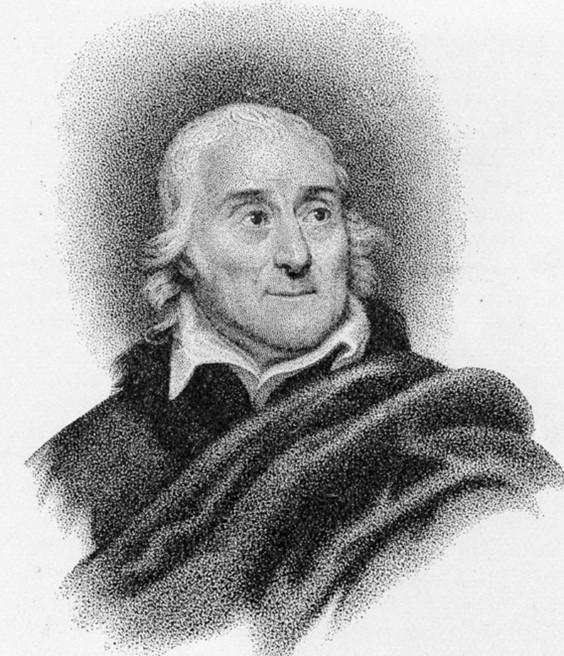

But, again, back to 1776. Louis was also dealing with another multitalented genius who sparked controversy: Pierre Augustin de Beaumarchais, who at this point was in his 40s and had already had a colorful, varied career that included being a renowned watchmaker, a musician who played and taught the harp for the court of Louis XV, a diplomat and spy, and a playwright who the year before penned The Barber of Seville, the first play in the Figaro trilogy that became his most famous accomplishment. He was already getting a reputation as a troublemaker - an earlier play of his inspired Louis XVI to say “this man mocks everything that must be respected in a government” - but the French court continued to employ him. The Barber of Seville (based on characters and situations from his own life and particularly his eventful sojourn in Spain, which also included events so dramatic they inspired a play by Goethe called Clavigo) was already becoming an international hit, with a production in English opening in London - but Beaumarchais soon turned his attention back to one of his other passions, championing social justice and liberty. On August 18, 1776, he wrote a letter to the Committee of Secret Correspondence, consisting of several members (including Benjamin Franklin) of the Second Continental Congress and mostly concerned with securing foreign aid for the revolution, in which he offered his services as an arms dealer for the Americans: “Your deputies, gentlemen, will find in me a sure friend, an asylum in my house, money in my coffers, and every means of facilitating their operations, whether of a public or a secret nature…I have procured for you about 200 pieces of brass cannon, four pounders, which will be sent to you by the nearest way; 20,000 lbs. of cannon powder….and lead for musket balls.”

Louis XVI didn’t want to break openly with Britain, but he quietly enabled and supported Beaumarchais’ project, which also had support of the Spanish government. The victory by the Americans over the British army in the Saratoga campaign of 1777 was made possible by the armaments supplied by Beaumarchais, and it was considered a turning point in the war.

After this triumph, Beaumarchais returned to writing, and completed The Marriage of Figaro in 1778. It was even more successful than its predecessor, and naturally ran into more censorship problems. Louis XVI temporarily banned it, a move disapproved of by Marie Antoinette. Benjamin Franklin enjoyed the play when he saw it in Paris in 1784. French revolutionary leader George Danton said the play “killed off the nobility”; Napoleon Bonaparte called it “the Revolution already in action.” Mozart’s operatic version, premiered in 1786, has never left the repertoire, and, until the advent of the early music movement, was the oldest opera regularly performed in high rotation by major opera companies.

And it has its own American connection: its librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte, was perhaps as colorful a figure as Beaumarchais. After a series of misadventures, he ended up escaping his debts by moving to New York in 1805, where, like the enterprising immigrant he was, worked as a grocer and Italian tutor before gaining a secure foothold in NYC’s culture, teaching Italian literature at Columbia and establishing the first opera house in the United States. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen at age 79. He died ten years later and is buried in Cavalry Cemetery in Queens.

So perhaps, when looking for a major classical work to celebrate America’s independence, you could do worse than simply treating yourself to listening once more to Le nozze di Figaro. Sure, you could listen to a more overtly political and nobly stirring opera like Beethoven’s Fidelio or Verdi’s Don Carlos (based on a play by Schiller), both with their own Sturm und Drang connections; Candide, with its connections to Voltaire and the Enlightenment, would also be appropriate. It’s also a good time to listen to William Grant Still, Aaron Copland, Duke Ellington, Florence Price and Arturo Marquez. Or maybe just your neighbor’s kid practicing his scales and preparing the future of American music.

But I do have a special love for Figaro. I am sure I’m not alone in its being the first opera I got to know and fall in love with. It preserves Beaumarchais’ revolutionary spirit by reminding us that the personal is political and vice versa. It gives us male and female characters that are fully fleshed out and seem like people we know. And it gives us music of the very highest order that depicts humans in all their imperfections, insecurities and frailties - perhaps the greatest music ever written that isn’t about gods or heroes and their cosmic and noble acts, but about things like lust and revenge and petty jealousy and a 12-year-old girl’s fear that her world has collapsed because she lost a pin. And the ending illustrates the empowerment of forgiveness; the Count may not deserve redemption, but the Countess needs to take that step in order to stop being his victim. A lesson for us all. In being a tribute to the universality of human experience on all levels of social strata, and its lack of embarrassment for being less than lofty, it’s actually quite a good illustration of American values and humor, like irreverence mixed with empathy. Its literary authors have American bona fides, Mozart has always been popular in the United States even during his lifetime, and - couldn’t we all use a laugh, beautiful music and a happy ending right now? That itself would be a revolution in action.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.