It's always a treat to hear a recital by renowned pianist Emanuel Ax. The Washington community looks in great anticipation to his recital on Sunday, April 16, 2023 at Strathmore, a presentation of Washington Performing Arts. Ax is known for his brilliant tone and thoughtful interpretations. His recital program is of compositions by two musical giants -- Franz Schubert and Franz Liszt -- written at transformative periods of their lives. The full program is noted below.

I asked Mr. Ax about this program.

Linda Carducci: Your program bookends two piano sonatas of Franz Schubert written at different periods and under different life experiences. The A major sonata is generally genial in mood, written when he was 22 years old while spending a carefree summer in the countryside. At the time, Beethoven, whom Schubert venerated, was in the throes of composing his final, monumental piano sonatas. Although their styles were different, is there a connection between the Schubert and Beethoven sonatas?

Emanuel Ax: Schubert was in some ways more conservative in choosing the way he built structures. Beethoven was always experimenting with length of development, with repeats, with the way things are balanced in terms of timing. The incredibly revolutionary things Schubert did were mostly harmonic. Of course, he had a wonderful gift for tunes, as did many of those great composers. But Schubert’s harmonic language is a wonder. You find yourself in the most remote keys, through the most remote modulations, without being aware that anything outrageous has happened. When Beethoven makes an unusual modulation, it’s very much in your face! Beethoven wants you to know that this is something special, revolutionary and different. And that’s true of his structures, as well. If you ask someone to play the slow movement of a Beethoven cello sonata for an encore, they can’t do it because there’s actually no slow movement that stands alone in any of the five sonatas. Beethoven was always experimenting with that.

Schubert doesn’t look to make it obvious, but we find ourselves in keys that we never thought possible, and without ever having been aware that something incredible has just happened. All of a sudden, it’s like a dream where you wander from a city to a field without every having felt that you made that trip. That happens quite a lot in his music.

This A major sonata is incredibly beautiful and lyrical, with a fun last movement. All with wonderful, wonderful modulations that just happen.

LC: The harmonic inventiveness you mention is often applied to Schubert’s final trilogy of piano sonatas. But you find it present in this early sonata of a 22-year-old.

EA: Oh, yes. Look at the last [third] movement: Schubert uses a device where the recap where he starts on a four to get back to the tonic through unbelievable means, finally sliding back into A major. It becomes revolutionary through these side trips.

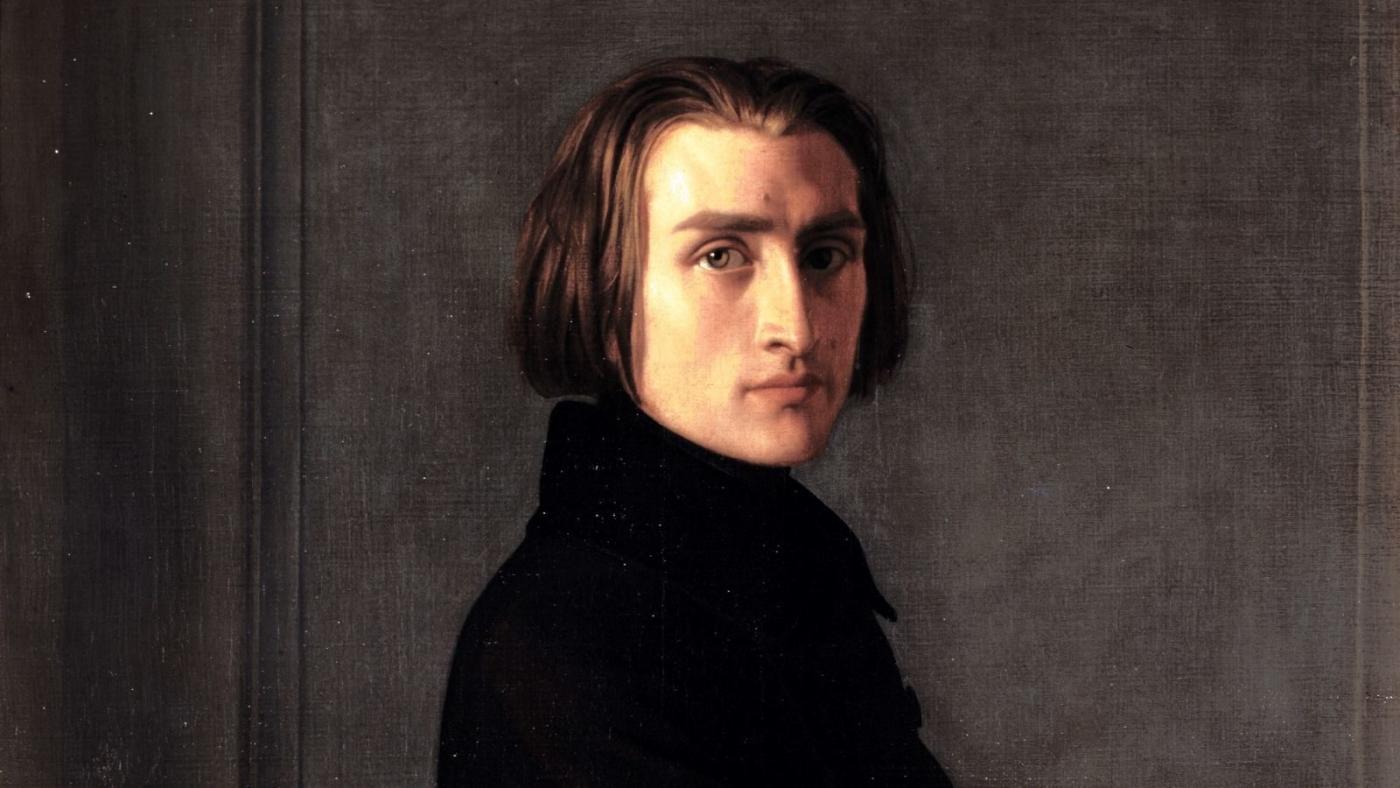

LC: The interior of your program is devoted to the formidable Franz Liszt: His arrangements of Schubert songs and Vallée d'Obermann from his lovely Années de pèlerinage: Première année: Suisse piano cycle. First, tell me about his transcriptions of Schubert songs.

AX: Liszt was, of course, one of the greatest pianists of the 19th century, and probably of all time. And he was totally in love with the music of Franz Schubert. Which is why he transcribed everything of Schubert’s that he could get his hands on: a lot of songs, including the Schwanengesang, and the Wanderer Fantasy, which he transcribed for piano and orchestra. I’m sure at some point, Liszt was aware of Schubert’s sonatas. The songs themselves are amazingly beautiful. But Liszt found a wonderful way of making it possible for pianists to perform these songs without words. Difficult, of course, but wonderful to work on.

LC: Vallée d'Obermann from Années de pèlerinage: Suisse was inspired by a novel about a man searching for meaning and longing for knowledge in a confusing world; he ultimately concludes that only feelings are true.

EA: The whole Années de pèlerinage is music that is deeply felt. Heartfelt, beautiful music brilliantly written for the piano. This particular piece is probably the biggest piece in the Suisse cycle – probably the centerpiece. I think of it as a miniature Liszt sonata. In this work, Liszt quotes some of the purported letters of Obermann on the facing page; you can read them. They’re quite pessimistic.

LC: Liszt composed this cycle in his middle age when he was settled in Weimar and chose to cease the hectic life of a touring virtuoso to focus on serious composition. Is it possible that Liszt was drawn to the Vallée d'Obermann story at this point in his life because he related to the life journey of its hero? If so, how is that reflected in this composition?

EA: I believe he was at some point deeply influenced by his admiration and friendship with Richard Wagner. And I think Liszt wanted to write music in that way. Also, within the Romantic movement was the idea of a solitary hero somehow making way through life, as opposed to a member of a society, a sort of functioning functionary.

Vallée d'Obermann expresses a yearning, the way Lord Byron’s poems expressed the yearning of making a difference in the world, but also of being alone in the world and a sort of hero of one’s own life. That theme is present in a lot of Liszt’s music. The piece was also possibly influenced by Hector Berlioz, who was always his own hero – Harold in Italy, Symphonie fantastique.

LC: Now to the closing bookend of your program: Franz Schubert's mighty Piano Sonata in B-flat. It is the finale of his final trilogy of piano sonatas composed during Schubert's final months of life, when illness and death loomed. In contrast to his earlier, genial Sonata in A major, there is deeper emotional expression, richer textures, and harmonic and structural exploration. Some call the work "otherworldly" elements of heaven and hell, punctuated by ominous trills that recur in the bass like a demonic summons from the beyond. How do you interpret this highly personal sonata?

EA: The first movement takes so many different moods, with so many different ideas. There’s a beautiful phrase, then suddenly we hear a bass trill and say “What is that? What is going on?” I don’t see it as demonic at all but rather, something we question: is it a rumble of thunder? A murmur, or something else? Nobody knows. It’s one of the great mysteries of the 19th century.

And the amazing thing about that first movement is the bass trill that recurs, once very loud and the other times not loud. At the end, it’s repeated for the last time. But never an answer to our question. And then the movement just ends.

If we want to contrast it with, let’s say, Beethoven’s Appassionata sonata, Beethoven places a recurring theme that finally comes to an end. And in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, he creates incredible tension that is always resolved. In this first movement of this Schubert sonata, there is a sort of tension but no resolution or answer. It remains mysterious. And that’s what draws people to it.

The slow movement of his sonata is the definition of tragedy. There is nothing sadder than this movement. And then the third movement is a kind of lighthearted transition from the tragedy we’ve just heard – it’s as though Schubert is saying “Let’s go away from that. Let’s think of paradise.” In this last movement, I do think we get an answer because there is a constant, repeated note – a G – that finally goes to F and seems to say, “Ah, we’re finally there.” So maybe we can look to this last movement as a kind of bookend or an answer to the first. One of the nice things about music is that we can always make up our own story, and neither of us is wrong.

Emanuel Ax’s recital is Sunday, April 16, 2023 at 4:00 p.m. at Strathmore.

PROGRAM

FRANZ SCHUBERT - Sonata in A Major, Op. posth. 120, D.664

SCHUBERT/arr. LISZT - Four Songs

"Aufenthalt," S.560, No. 3

"Liebesbotschaft," S.560, No. 10

"Der Müller und der Bach," S.565, No. 2

"Horch, horch! die Lerch," S.558, No. 9

FRANZ LISZT - Années de pèlerinage I, S.160

"Vallée d'Obermann," No. 6

SCHUBERT - Sonata in B-flat Major, D.960

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.