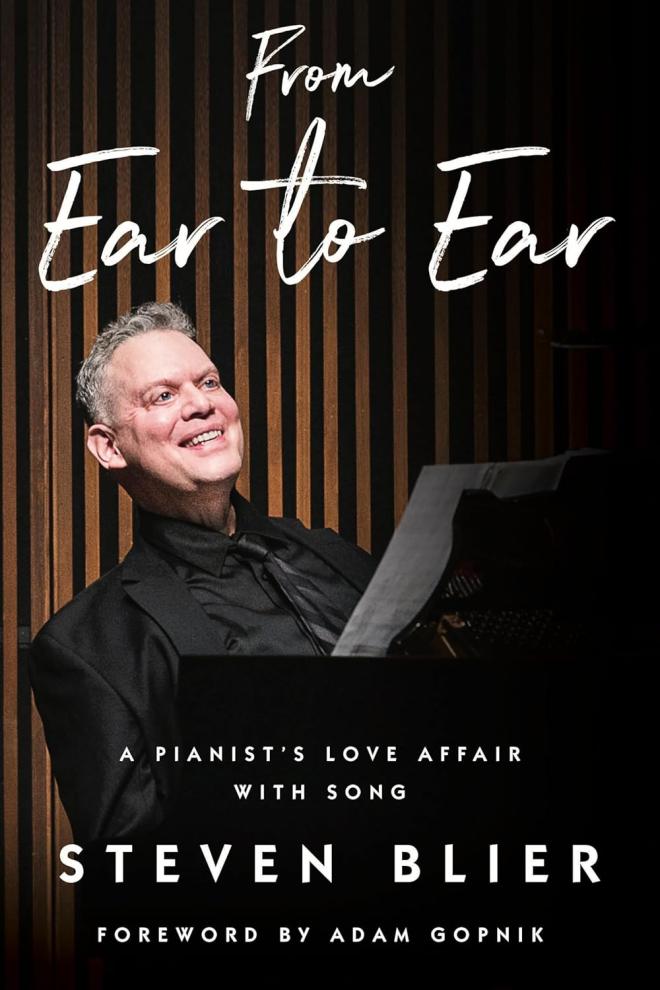

Pianist Steven Blier tells us in his recently-released memoir, “From Ear to Ear”, that he considers himself “a song guy, a kind of musical jeweler.” That’s probably a humble characterization of a pianist who has collaborated with some of the most renowned vocal artists of our day – Renée Fleming, Jessye Norman, Susan Graham, Cecilia Bartoli and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, to name just a few. To further his love of song, Mr. Blier co-founded New York Festival of Song in 1988, a vibrant concert series that dips freely into six decades of vocal music from all genres. He also is a vocal coach at the Juilliard School. Of course, Washington, D.C. area audiences are familiar with Mr. Blier through his performances at the Kennedy Center, and his annual concerts with Wolf Trap Opera.

Here's my recent conversation with Steven Blier about his memoir, his life, his challenges and achievements.

LC: You had traditional classical piano training from childhood through college, but you mention that the traditional, highly-structured course of study didn’t fit your personality or how you heard music. You said your interest and talent lay in a more “instinctive connection” and that “music was all about colors passions, swirls of melody, slashes of drama — not numbers."

SB: I studied piano, and I was not bad at music theory, but my real goal was to find the music within me. Some of my teachers were able to fan that flame, others did their best to extinguish it. I have never done too well when things were imposed on me in a rigid way.

LC: Your piano study with Alexander Farkas at Yale included the Alexander Technique, which focuses on body alignment, posture, and freeing tension that would allow fluidity and expressiveness. You speak frankly in the book about living with a form of muscular dystrophy, although that never slowed your goals or career. Has the Alexander Technique helped you throughout your career?

SB: It helped me tremendously in the first 30 years, and still draw on it now. I use it to release tension; it makes me aware of where I am gripping, of where I am tensing. Because of muscular dystrophy, a lot of my functional muscles are picking up some of the slack from some of the ones that are weak. In my body, the relative areas of strength and weakness are not normal. So the Alexander Technique continues to help – I can feel and understand the tension in my arms, for example, and feel them release. The full-on Technique is harder for me to do now, but the basics still come to my aid. By the way, I see Alex Farkas from time to time, and he still gives me instruction. He’s kind of a miracle worker—with the lightest of touches he can restore a kind of energetic balance in my arm and help me release tension. I would be nowhere and have no career without his instruction – I simply couldn’t play. The book is dedicated to him and to my husband.

LC: Tightening up can become a habit for pianists as they play forcefully or loudly.

SB: For sure. And you don’t even know the tension is there until it goes away.

LC: You’re sometimes asked to explain the difference between an accompanist and a collaborator, the latter being a partner with a soloist, working together toward a shared vision of how to interpret a piece. You explain in the book, often in witty passages, that sometimes a singer's personality takes a dominant role so that you had either to diplomatically suggest an alternative concept or simply go off a musical cliff with them. But I’ve heard of cases where an interpreter slightly modifies a piece, say, during a rehearsal, and the composer actually prefers the modified version from the original. Have you experienced that? Have there been times where you interpret something differently from what a singer or composer conceived and they prefer your interpretation?

SB: Yes. Generally, I have had good rapport with composers I’ve worked with. I can only think of one who wanted to control everything – every note, every nuance, every pedal depression and release. He wanted it to sound exactly as he envisioned it. That was tough. That tight control doesn’t actually produce musicality because the performer becomes so mechanized that nothing spontaneous can happen. No freedom, no humanity. But I worked with him a few years later—with great trepidation—and found him open-minded, a bit skeptical at first but finally welcoming a very different interpretation of his piece.

LC: You’ve worked as a pianist with some of the great singers of our age. Different singers have different styles, different rehearsal expectations, different ideas about interpretation. I imagine there’s both a joy and challenge to this.

SB: Certainly. There’s no cookie-cutter approach. Cecilia Bartoli, for example, could lead me like a great conductor—I always knew how to phrase with her, what kind of colors and dynamics were needed. She didn’t like to rehearse very much, and if I started a song at the wrong tempo, she would flash me a beautiful, conspiratorial smile that said, “Don’t worry, I’ll fix it when I come in, go with me.” Cecilia really listened on stage; together, there was intimate music-making. She felt like a collaborator, like a member in a jazz group.

LC: In addition to having a distinguished career as a musician, collaborator and Artistic Director of New York Festival of Song, you’ve worked for many years at Juilliard as a voice coach. Has the way you’ve approached music your entire life – following its spirit, discovering its purpose rather than strict conformance to standard practices -- informed the way you teach them?

SB: Yes. And recently my work has begun to include other collaborative pianists, which is a real joy. When I work with them, I encourage them to start by understanding the character of a piece: what is the “event” of the song, who is the protagonist or narrator, what is the song saying—and what is it not saying? Why do they need to say this? What happens to them as they sing the song? From there, you find the color and weight of the piano part. For example, a student was recently studying Fussreise by Hugo Wolf -- a song about a walk in the German countryside, full of joy, in rugged terrain. He was performing it very well, but it was a little lightweight and flouncy for my taste, ballet slippers instead of hiking boots. I could have told him “You need more weight on this note,” or “make your rests shorter.” But instead, I want students to feel a song and feel the character of a song for themselves. I know that’s the case for me. And there is a way to guide them, to educate them, to show them style and phrasing, without turning them into robots. I am always trying to release their natural musicality.

I should add that you can only do this if you know and respect the traditions behind a piece of music. This isn’t a free-for-all. It’s an exploration of the essence of a song.

LC: What’s the difference between musicianship and musicality?

SB: Musicianship is knowing the mechanics: how to count beats, knowing when to come in, knowing the basics of different styles, how to phrase, and most of all being ready for the first day of rehearsal—even if you have a co-star who can’t count to one, or a maestro intent on destroying you. Musicianship is your foundation. Some students need to increase their skill, but Juilliard is pretty rigorous in that department. Musicality, on the other hand, means the inner glow, the heart-to-heart communication, the feeling of lift-off as the music sails into the air and stimulates the listener’s imagination. Not just that everything is correct and in place. Young singers often sing defensively, and it’s easy to understand why. They are constantly getting contradictory feedback from so many people. With good reason they want to avoid making a conductor angry, or making some musical choice that some rando might not like. They’re singing for purists and free spirits, scholarly people and blissfully uneducated voice-lovers. And everyone has an opinion, sometimes quite strident. That can lead to a very conservative approach—to something safe that won’t anger anyone. I try to wipe that away and get back to what drew them to this piece, what’s in it that captures them, why it needs urgently to be sung. It takes courage to be an artist.

LC: One of my favorite parts of your book – and one of the most entertaining -- is the chapter on performing and recording Leonard Bernstein’s Arias and Barcarolles and everything that involved, from the rehearsal process and singers challenged by Bernstein’s rhythms, to the recording process, and especially your group’s presentation of the final recording to Mr. Bernstein himself. And this was before As & Bs was recorded with orchestra.

SB: I’m so glad you liked that. That experience of performing and recording Arias and Barcarolles was challenging and exhilarating, and it happened during the second season of the New York Festival of Song. What a launching pad.

LC: I’m glad you mentioned that, because NYFOS is a big part of your career and it’s still going strong. You’re Artistic Director of NYFOS, which you co-founded in 1988 with Michael Barrett. The slogan is “No Song is Safe From Us.” NYFOS gives listeners and singers an opportunity to experience a wide variety of song — lieder and other art song, popular song, cabaret, Broadway, contemporary music, ensemble singing. Many vocal greats have performed in NYFOS concerts. One of the hallmarks of NYFOS is thematic programming. It must be a challenge, and maybe a stressful joy, to decide on a theme and select the music for each concert, but a different challenge to find singers who can deliver the art and who are available! How does that work as a programmer and manager?

SB: I usually start with specific music, even a single song, or a specific theme; alternatively, I might begin by cooking up something for a performer I want to work with. Then it’s all about lists: lists of songs, topics, ideas, colleagues. And sometimes a singer around whom you based a program suddenly becomes unavailable, a disaster which has often led to an even better result. For example, we recently presented an Argentinean program and the original singer cancelled about six weeks before the performance. Someone directed me to an Argentine bass-baritone I hadn’t heard before -- Federico De Michelis -- who turned out to be the Buenos Aires balladeer of my dreams, even better suited to the project than the person who cancelled. There are these moments when you think you’re cooked, and then the most incredible stroke of luck will happen. I ended up making a CD of Argentinean songs with Federico called “Mi país,” and it is among my very favorite recordings.

LC: NYFOS’s “Ned at Ninety”, a tribute to Ned Rorem on his 90th birthday, was a truly inspired, creative program.

SB: Yes, we wanted a bit more variety in the playlist than just Ned’s music for an entire evening’s concert. But how to do this without abandoning the birthday boy? I came up with the idea of researching Ned’s memoirs (of which there are many) to find his aphorisms about other musicians he was close to – artists like Virgil Thomson, Poulenc and Bernstein. We then interspersed pieces by those composers with Ned’s music, and introduced each with a reading of Ned’s words about that composer. It was a great success. We brought that concert back with a new title—“Ned at 100”—to mark his centenary, and it worked beautifully.

One of the most interesting of NYFOS’s programs was “Schubert/Beatles”. When baritone Theo Hoffman, one of my students at Juilliard, approached me with the idea of combining these two genres of music into one thematic concept, I almost fainted. But it turned out to be a wonderful pairing and one of my favorite NYFOS memories. Franz Schubert and the Beatles were around the same point in life when they wrote their iconic songs; there is often a strain of melancholy in their most joyous music; and in their different ways they are experts at capturing the confusion of young love. In the NYFOS program, we creatively interwove their songs on similar themes, sometimes dovetailing them, to great effect. We recorded “Schubert/Beatles” with Theo Hoffman, Julia Bullock, and Andrew Owens, and the CD is available on the NYFOS website (and every streaming platform known to man). And it just got nominated for a Grammy, a very big event for our fledgling record label.

LC: So there’s an arc to creating a thematic program for NYFOS — where to start, where to end, what to fill in between to create a narrative. Would you say you had the same challenge when you were writing this memoir?

SB: To a certain extent. Robert Weil, an Executive Editor at Norton, buttonholed me with this advice: “Don’t write one of those ‘and then I did this, and then I did that’ books. They get tedious. Just make an outline and write 14 essays.” That liberated me to start with a structure. From that, things filled in and the book took shape.

LC: The ubiquitousness of music now — access it anytime, anywhere, anything you want to hear — makes music available without going to the concert hall. Have you found that this has changed our musical habits as listeners?

SB: I think music is so ubiquitous that it’s become background music for so many people—a constant ambient soundtrack. I’m finding that people don’t have the same capacity to listen to music – not just hear it -- and concentrate on it the way they used to. In the past, most people knew what it meant to go to a concert hall and share music as a communal experience, but now it’s getting rarer and rarer. Listening to music in an audience is such a different experience from listening via headphones, not just alone but completely cut off from the world. A shared experience deepens our enjoyment and understanding of what the music is communicating, increasing its impact. At NYFOS, we try to promote our concerts in a way that entices an audience to leave their home, brave the subway, and participate in something that needs to be experienced live—not on-demand.

LC: Has this private, on-demand way of listening cut into your NYFOS audiences?

SB: It’s dug into everyone’s attendance. But our NYFOS concerts are based on song, and songs are typically short, so the components of our concerts are broken down into three- or four-minute spans. That’s an advantage for some new listeners. But if you can’t attend a NYFOS concert in person, just check the website for our recordings—yes, you can get the NYFOS message at home. https://nyfos.org

LC: Your career isn’t over, but it is a nice time to reflect on what you’ve accomplished. You say in your book that you would sometimes go into a project with a mixture of self-doubt and unbridled chutzpah! You also mention that luck played a role in opening opportunities to work with great artists and expand yourself creatively. But certainly your skill and talent, not to mention perfecting the nuances of interpersonal relationships and your persistent determination, have played a valuable role.

SB: Thank you, and yes, I can look back at many great experiences. One of them just came full circle – my interaction with the soprano Valerie Masterson. When I was just 13 and plunging headlong into music with my high school friend Matthew Epstein, we met Valerie, who was performing with the D’Oyly Carte Opera in New York—the premiere British purveyors of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas since their very first performances. I was in awe of Valerie, a total fan boy. Matthew was an accomplished stage-door Johnny, and she got Valerie to have supper with us, and then go to Matthew’s apartment where she sang some opera arias. I accompanied—she was the first professional singer I ever heard close up. It was a profound experience, and it changed my life. Then, just a few months ago—and 60 years after that evening—I wrote her an email to tell her about my book. Amazingly, she wrote back with an astounding revelation: she not only recalled that evening, but she said that it had changed her life as well, enticing her into a career in opera, instead of going to Hollywood as planned, to be the next Julie Andrews. Valerie began my association with singers, and dropped back into my life to hand me the end of my book.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.