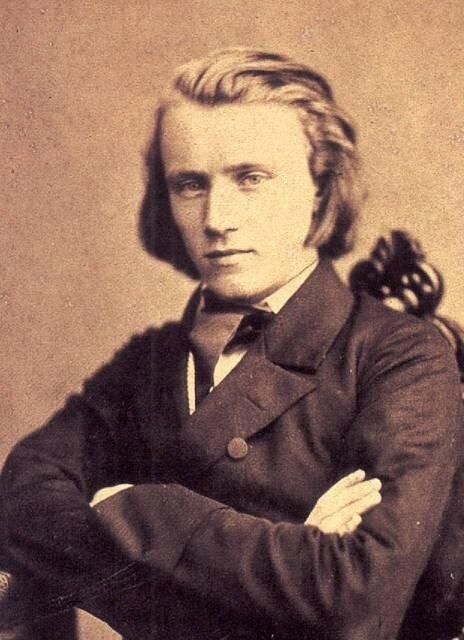

Think of choral music by Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), and what immediately comes to mind is Ein Deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), and with good cause. It’s a masterpiece, one of the best-loved pieces in the repertoire. But what about his other choral works? Maybe you’re aware of his shorter, chorus-and-orchestra pieces such as Nänie, Shicksalslied, “Song of Destiny”, or maybe the Alto Rhapsody. Even so, you would still be only scratching the surface. Brahms wrote quite a lot of vocal music, both sacred and secular. He loved ancient music, i.e., works by Palestrina, Victoria, and of course, Bach – and he studied it assiduously, becoming a master of both voicing and counterpoint. He also loved leading amateur choirs; especially, women’s choirs. He founded and conducted the Hamburg Ladies’ Choir, and years later even became chorus master of the Vienna Singakademie (I’m told he was even offered the post of cantor at St. Thomas School in Leipzig, Bach’s old post, but he turned it down – comfortable with his life and career in Vienna.) All of this bore fruit with his own compositions, choral music of great depth and variety, and complexity, too: these are some of the most challenging pieces to perform, but also some of the most rewarding.

I’m not quite sure what makes them so captivating, but some years ago I treated myself to a collection of choral CDs that just happened to include a recording of secular songs by Brahms. It was not the main reason I purchased the set, so I was not expecting much, but I was blown away by the romantic melody and tonal color. This is the kind of music Brahms wrote for the Hamburg Ladies’ Choir. Not wanting to be tied down to strict counterpoint, and searching for a more authentic voice, he turned to folk song. One set, the enchanting Four Songs, Op. 17 are delicately ornamented with two horns and harp. Among others, the Liebeslieder and Neue Liebeslieder (“Love Song”) waltzes reflect his love and admiration for the music of Franz Schubert, and that of his friend, the waltz-king Johann Strauss II.

Brahms may not have been a very “religious” person, but his love for sacred music knew no bounds. He began writing his own, much of it for unaccompanied choir, in his early years and continued throughout his life. If you guessed that his study of Renaissance music and baroque counterpoint would come shining through, you guessed correctly. His Motets, Op. 29 sound almost Bach-like; an early mass, the Missa Canonica, was left incomplete but showed great promise. Of particular note is the Geistliches Lied, Op. 30, Las disch nur nicht dauren mit Traueren, “Let nothing distress thee with grief.” A perfect gem that, in just a little under five minutes, covers the same sound world and sense of consolation as the beloved German Requiem.

A journey through the vast choral works of Brahms could provide a lifetime of pleasure, but we’ll take an evening to explore just a few on Choral Showcase, Sunday, August 20 at 9pm, and I hope you’ll join me. Not so much of a “deep dive,” perhaps, but maybe we can just wade in and get our feet wet!

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.