The death of Alfred Brendel on June 17 at the age of 94 has prompted an appropriately laudatory stream of reflections globally. One of the most revered pianists of his generation, he was also an essayist, poet, composer and humanitarian. Many an eloquent obituary has been penned, and tributes by Angela Hewitt, Simon Rattle, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Steinway & Sons, Classic FM and many others have resounded throughout the world. Rightly so.

There is not much I can add to these well-deserved accolades, and the facts of Brendel’s long and remarkable life need little illumination from me. His vast discography and decades of concert appearances, his many publications and public statements speak for themselves, and even a perfectly decent Wikipedia entry on him is as good a place as any to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding of this vastly creative and astoundingly gifted individual.

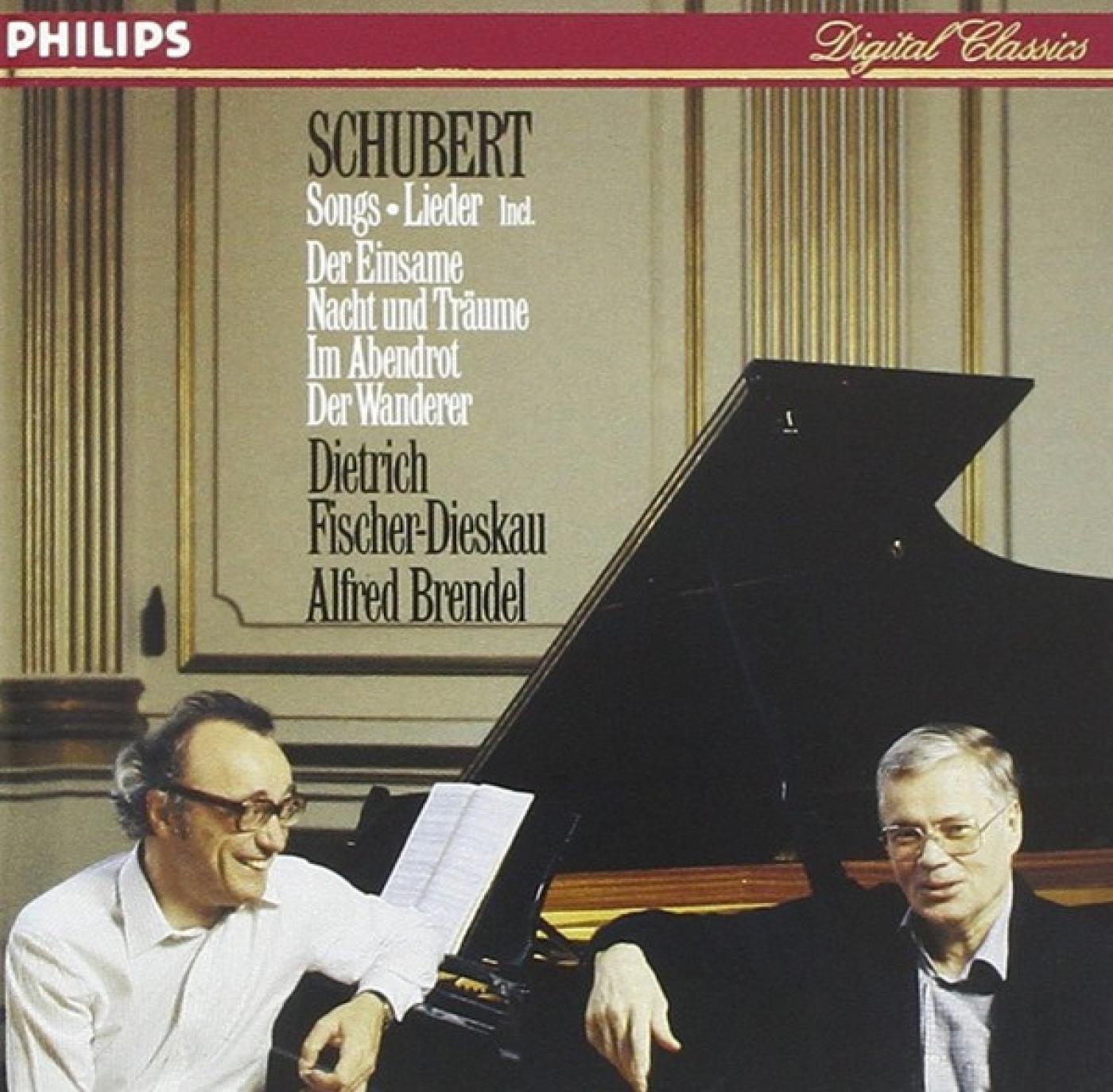

My own reflections on Brendel’s life and death take me back to my adolescence: I must have listened hundreds of times to this 1983 album of Franz Schubert lieder he made with baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieksau.

It is a glorious recital, not quite an hour long, of fourteen of the incomparable gems from the mountaintop that is Schubert’s output of over six hundred songs. Included here are the three Gesänge des Harfners — verses from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister — and “Der Wanderer,” Op. 4 No. 1, an 1816 composition which he revisited in perhaps his most demanding solo piano work, his 1822 Wanderer Fantasy. I loved them all, but the song that commanded my most profound reverence was “Nacht und Träume”.

I was enough of an un-ironic nerd that when a classmate taking a survey for our high school’s newspaper asked me what my favorite song was, I didn’t cite the Bangles or Huey Lewis and the News (artists I largely ignored at the time, but who I have since come to appreciate very much); I answered honestly that my favorite song was Nacht und Träume by Franz Peter Schubert. If I had been more self-aware, I would have admitted that it was this interpretation of it by Brendel and Fischer-Dieskau that I loved more than any other song.

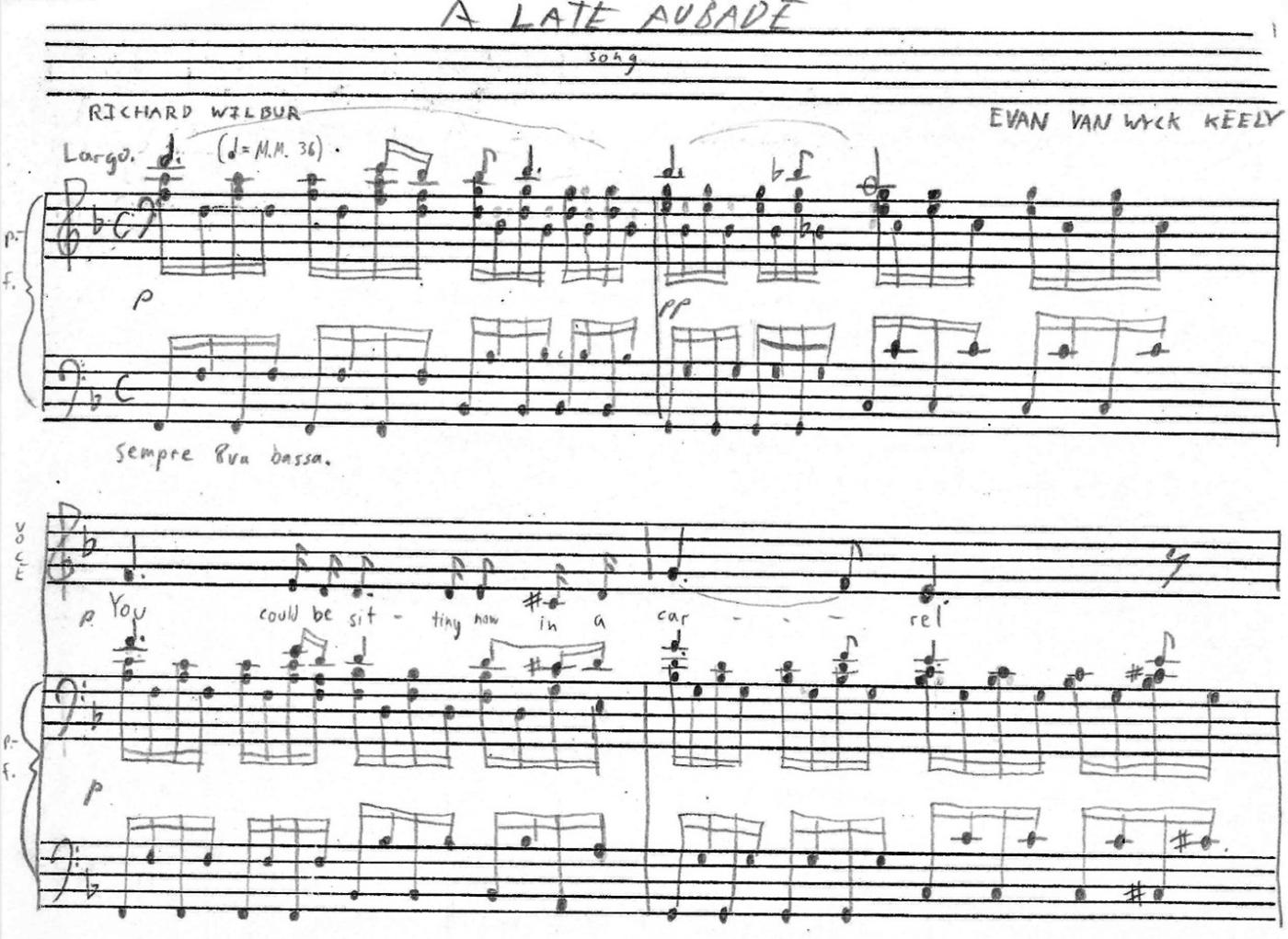

Before graduating high school, I even composed a song (on a poem by Richard Wilbur) in the style of this Schubert lied.

In retrospect, my callow composition was more of an homage to Brendel’s exquisite playing than an exercise in personal creativity. The amorous situation depicted in the poem was as familiar to the naïf teenager I was as the dark side of the moon, but how deeply I could relate to and appreciate the intellectual depth, the sensitivity, the nuance, the integrity, the honesty, the emotional centeredness of Brendel’s rendition of this flawless Schubert song from 1825, perfectly coupled with the extraordinary insight of Fischer-Dieskau. Here were two of the great interpreters of Schubert of their time, coming together to produce truly stupendous renditions of some of his greatest works.

A few years later, Brendel and Fischer-Dieskau recorded Schubert’s Winterreise and two of the great Robert Schumann song cycles, the Dichterliebe and the Op. 39 Liederkreis.

I little imagined as a teenager that later in life I would be a classical music radio host and producer, sharing that 1983 album with our audience on WETA VivaLaVoce on a regular basis, but here we are.

I’m grateful for our audience, and I’m grateful for the magnificent Alfred Brendel.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.