Contrary to popular belief, it was the string trio and not the string quartet that was the dominant chamber music combination of the classical era (ca. 1750-1825). The string trio usually consisted of violin, viola and cello, but sometimes, harkening back to its roots in the Baroque trio sonata, it was two violins and cello. Except for a handful of works by Mozart and Beethoven, this repertory has been almost completely ignored for the last two centuries.

Seeking to remedy this situation is The Vivaldi Project, founded by violinist Elizabeth Field in 2006 as an ensemble devoted to performing Baroque music on period instruments with a strong educational component, working from original manuscripts and coaching musicians in what has become known as Historically Informed Performance (HIP), techniques and expressive gestures that would have been part of an 18th century musician’s vocabulary. In the last several years they have concentrated on the string trio repertoire, digging through library archives in search of music needing to be rescued from obscurity, much of which hasn’t been played since the composer’s lifetime. They have just released the final disc of their four-volume recording project that began in 2016. Volume 4 includes works by both the well-known (Boccherini and Haydn) and the deserves-to-be-better-known (Joseph Schmitt, Simon Leduc, and Maddalena Sirmen, about whom we’ll hear more a bit later in this article.)

In this conversation, cellist Stephanie Vial told me about the astonishing discoveries she has made in bringing this body of work back to life, and we also did some bonding over our shared instrument, the cello.

James Jacobs: Way back in the 1980s when I was a budding Baroque cellist in the Bay Area (life has taken another direction since then), I participated in a master class with Susie Napper. I brought along two friends who played violin and harpsichord. As she coached us she told us that the cello is the true driver of a chamber ensemble, that how I placed each note could determine how the others in the ensemble played theirs in terms of establishing the particular nuances of rhythm, phrasing, and harmony, and that the other two in my group should follow my lead.

Later I had the honor of being coached by Alan Curtis, who in turn made it clear that the harpsichordist was the real conductor of any ensemble and I should always follow them, and when I was coached by Michael Sand he was adamant that it is the violinist that is the leader of all in his midst.

So you can see that I was the recipient of some mixed messaging (or perhaps it wasn't mixed at all, if the message is that everyone feels they play the most important instrument.) I'd like to start this by having you weigh in on what you see as the cellist's role as a continuo instrument, how that changed and didn't change as the Baroque era transitioned into the Classical and early Romantic eras, and how the cello can quietly establish dominance even when playing with two other people mistakenly convinced that their instruments are more important than ours.

Stephanie Vial: I absolutely love this story. Let me start by saying how lucky you were in your excellent coaches! In a sense, as you point out, you didn’t really receive mixed messages, more a lesson in the nature of chamber music. Every member of the ensemble is important and must both lead and follow. But I do think that the role of the cellist in music from the Baroque and Classical periods is exceptionally important and foundational. I try to see myself as more of an enabler (in the positive sense hopefully) than an outright leader. In my mind the best continuo players are indeed the drivers, but in a way that makes the melody instrument feel as though they are in control. My goal is to provide the accompaniment textures, rhythms, and harmonic twists and turns in a way that offers both stability and freedom for the violinist. The worst thing I can do is to play too regularly or evenly and force them into a kind of musical straight-jacket. I know I’ve done my job really well when I can suggest an affect, nuance, or phrasing idea through my playing (sometimes with the placement of a single note) and the violinist thinks it was their spontaneous, expressive idea.

As the string trio repertoire is essentially Galant and Classical in style, I find that attention to phrasing and structure in the bass line is both crucial and incredibly rewarding. The joy of playing J.C. Bach for instance (even though I rarely get the tune) is in understanding the pace of the underlying harmonic rhythm and how phrases combine, interrupt each other, and change on a dime to become something else entirely. I live for the moments, say in a minuet by Haydn, where the cello fills out the end of the bar and gets to decide exactly how it belongs both to the previous phrase and sets up the next one. As the cello becomes more and more integrated into the texture and takes on more melodic material, I get to move in and out of the continuo role. The violin and viola then need to step up and understand how to play bass lines for me!

JJ: Before we leave the Baroque era, I want you to help clear up a common misconception, an aspect of our modern adventures in HIP: you don't necessarily need a harpsichord or lute or organ to complete the basso continuo unless the composer specifically asks for it.

SV: The practice of using both a cello and a harpsichord in the continuo sonata repertoire is indeed much more commonly done today than historical evidence would suggest. Many of the early Classical string trios also indicate on their title pages the option of using a cello “or” keyboard to cover the bass line. Both of these facts point to how defining the boundaries of genres is a murky business at best. Genres are to some extent an artificial construct, and while history gives them clearly defined names, look how many of the works we are calling “string trios” go by sonata, divertimento or trio concertante, and more.

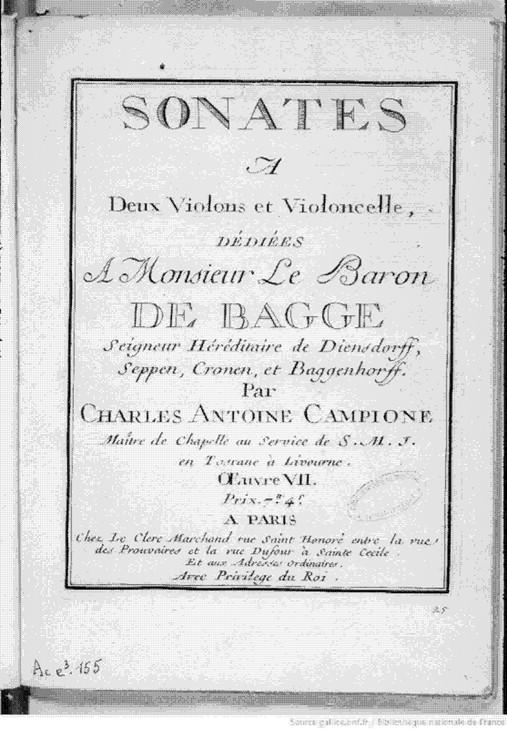

The trios we recorded by Carlo Antonio Campioni* (both for two violins with a thorough bass for harpsichord or cello) stand for me in this murky middle ground between a continuo part and a true cello part. The op.1 trio in G minor from Vol.1, a wonderful blend of French and Italian styles, would I think be equally satisfactory on either harpsichord or cello. While on the one hand it trends towards many of the hallmarks of the Classical style with slower harmonic rhythms and literal repetitions of phrases, its accompanimental bass line and forms (a 2nd movement gavotte and 3rd movement gigue) are very much in the trio sonata tradition. However, in the op. 4 trio from Vol. 2, I can’t imagine how a keyboard could do justice to the rich and gorgeous extended melodies Campioni adds to what feels like a true cello part. It could be done on a harpsichord, but then the shared tunes between the violins and bass line are so much more unequal in the way they are sustained and shaped.

To address the question you raised earlier about who is in charge when both cello and harpsichord are present (also sometimes specifically indicated, as in the case of Purcell’s trio sonatas à 4), I like to think it is a joint effort. After all, the instruments do wildly different things, and can together create textures, dynamics, and rhythmic energy they simply couldn’t achieve on their own. I definitely play differently when a keyboard is present, and make further adaptations depending on whether it is an organ, harpsichord, or fortepiano. Things get really exciting when a plucked lute or guitar is added to the mix. Being part of a continuo band is also one of the great joys in life!

JJ: There's a big difference in how one writes for three instruments instead of four: there isn't a single wasted note, nothing is there for mere texture or decoration. And I imagine that it feels different to play as well: with four people you can already fall into a kind of orchestral attitude and hierarchy, but when there's only three people everyone is a soloist. I imagine your group wouldn't be doing what it does if you three didn't feel on some level that playing in a trio is just more fun. Is it?

SV: Playing string trios is indeed fabulously fun and rewarding. Every part is always important. We do our fair share of fighting over musical details (though three players definitely get into fewer arguments than four) but mostly we are tremendous friends and have the utmost respect for each other. We of course spend a lot of time making sure we match our articulations and are playing as perfectly together as possible. But we also celebrate our individual voices. Allison and Liz [Vivaldi Project members Alison Edberg Nyquist and Elizabeth Field] are very different players and I think that brings a special energy and vitality to their dialogues. You can always hear which one of them is playing at any given moment. Modern string quartets tend to strive for a homogeneity and blending of sound, but the trio has allowed us to step out of that paradigm and find added expression in the clarity of the texture and variety among the voices.

String trios are also hard! The technical demands on the player become increasingly difficult over the course of the 18th century (pushing the instruments to their limit) and there is simply nowhere to hide in the texture. Very often one or more of the instruments is asked to play chords (in order to fill out the harmony) and intonation becomes critical. One has to listen very carefully both to the vertical harmonies and how the linear melodies fit into them. The trio and the quartet existed side by side in the latter half of the 18th century and it may be that the quartet eventually “won” at least in part because it was easier to play and perhaps also to write for.

The string trio repertoire is also a particularly wonderful resource for violists and cellists. Violists bemoaning the lack of Classical literature specifically for them will love works like the Zanetti trio of Vol. 3. The trio (and quatour) concertante, a term from the fashionable Symphonies Concertantes, were extremely popular. Each instrument gets its concerto moment. The second movement of the Wranitzky trio in Vol. 3 is like another Haydn concerto slow movement for the cello. And Boccherini’s writing in the op. 14 trios (Vol. 4) is off the charts!

JJ: One of the most persistent myths that your group is helping to bust is the idea that Haydn, Mozart, Boccherini and J.S. Bach's sons were shining lights in a period that was dominated by mediocrity and oppressively formulaic music. First of all, what is both true and false about that myth, but more important, what composers are we sleeping on? Who should we be paying more attention to?

SV: It is true that there are thousands of (mostly unknown) trios by hundreds of composers in the second half of the 18th century. And truth be told, many of them are just awful. Our sight-reading sessions are tedious affairs in which we groan and slog our way through many uninteresting works before we find the ones with potential. I don’t think we can deny that the likes of Haydn and Mozart are shining lights of the period, but neither did they exist in a vacuum. Our understanding of a language has to be richer if we hear more than just a few select voices speak it. And that is what we have found with the string trio, a genre which has been overlooked largely because the majority of its contributors, many of them revered in their own day, did not withstand the test of time. Yet their voices offer a freshness to our understanding of the Classical period's musical language. The forms too are so varied, from orchestral trios to virtuosic trios concertante. And while some elements of the music are indeed formulaic, much of it is wildly creative, individual, and even quirky. Engagement with period instruments and an understanding of historical styles is also an important part of the equation in appreciating what these works have to offer. There is so much expressive variety to be found in the notation that is not immediately obvious, and without which, the music falls utterly flat.

JJ: One composer who appears on your albums seems poised to be a breakout star, as she actually was during her life: tell us about Maddalena Laura Sirmen.

SV: After we read through Sirmen’s G major trio for the first time, we all looked at each other and said, “Beethoven.” Its opening, dramatic chords and driving bass line followed by eerie figurations weaving in and out of each other only to disappear to almost nothing simply stunned us. We were even more amazed when we considered that the piece was written in 1770, the year Beethoven was born.

Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen is definitely a composer we feel deserves more attention today. And her achievements are all the more remarkable given the constraints of women in her time. Classical string music written by women is rare, in part at least because the violin and cello (unlike the keyboard) were generally considered indecorous instruments for the “fairer sex” to play. This was not a concern among the charitable Venetian ospedali, which sought to cultivate the musical talent of the orphaned or abandoned girls in order to present all-female choral and instrumental performances, whose increasing fame drew ever larger crowds willing to pay to hear them play. The ospedali became the first music schools for women, and the best teachers (like Vivaldi at the Pietà) brought in to oversee the musical education of these figlie. At the age of 7, Maddalena underwent a rigorous audition to enter the Opedale Dei Mendicanti. She was only permitted to leave through marriage (and this only through the intervention of her illustrious teacher Tartini). She toured Europe and Russia as both a singer and virtuoso violinist and her published works were widely reprinted during her lifetime.

We are so pleased that in Vol. 4 we are able to include a trio that Sirmen never published. It survives in a single manuscript, which just happened to be in my own backyard at Duke University in the Rubinstein rare book library. Seeking out rare manuscripts from all over the world is one of the exciting aspects of our work, but it isn’t often we get to hold one in our hands. We have been lucky on a number of occasions, with the Klausek and Hofman trios from Vols. 2 and 3 (held by the Moravian Music Foundation in Bethlehem, PA and Winston Salem, NC).

JJ: If you don't mind, take us through a quick primer on sonata form. We hear this form a lot on your albums. It's actually not that complicated, and in many respects it's analogous to the form of novels and movies and television shows as well as some popular songs. It's a form of storytelling and rhetoric. For the uninitiated, what are some guidelines for how we listen to the movements on this album that are in sonata form?

SV: Sonata form is a wonderful way to tell a story. It provides a predictable format whereby composers can both organize their ideas and at the same time play with the listener’s expectations. Many of the sonata form movements in our trios begin like the introduction to a play or opera with a dramatic opening of the curtain. (I’m thinking of the big chords in Sirmen’s G major trio or the unison octave leap of Luduc’s F minor trio). This also establishes the home key called the tonic. The main melodies and themes of the story are then presented and take us eventually to a new related key, a 5th above the tonic, called the dominant. We have traveled away from home to a higher place with new vistas. This whole section is called the Exposition.

Then comes the part of the story where the plot thickens, also known as the Development section. Here’s where the real drama happens, where ideas from the Exposition are turned inside out and upside down and wander into strange and unexpected harmonies. The composer then begins to pull the plot back together, to resolve tensions and find one's way home to the original tonic key and its familiar themes. This arrival is called the Recapitulation. Sometimes the composer will trick the listener with a false recapitulation, presenting the familiar tune but in the wrong key. (You thought home was just around the corner, but the landmarks misled you.) The whole Exposition is then repeated. Except this time, all of the themes are recalled in the home key. Often a composer will throw in some new ideas and elements and even harmonies (rather than repeating the Exposition verbatim) perhaps to make sure you’re still paying attention or to comment upon what has been learned along the sonata form journey.

JJ: Having produced such a comprehensive survey of this repertoire, what's next for The Vivaldi Project?

SV: Classical string trios are just the tip of the iceberg for chamber music of the period. Recently we put together a program of rare clarinet quartets (clarinet plus string trio). We would also very much like to take the trios on tour to Europe, where we feel the repertoire would receive a warm reception. We also continue to enjoy music from the Baroque period and working with a slightly larger scale ensemble. In the Spring we will be playing Schubert and Boccherini for the North Carolina HIP festival. New music for period instruments? Why not!

JJ: Just because a group is named for a particular composer doesn't indicate any sort of exclusivity: The Monteverdi Choir sings Brahms, the Alban Berg Quartet plays Mozart, etc. But I do sense in the name "Vivaldi Project" a sense that you are continuing Vivaldi's project. He was such a pioneer in showing what string instruments are capable of and the many ways they can interact with one another.

SV: The Vivaldi Project is in a way a name that happened to us. It was the name of the file folder on Liz’s computer for the first project she organized involving Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. But it is an apt name, acknowledging one of history’s most important string players and his pivotal role between earlier Baroque and later Classical composers. Some presenters expressly ask us to program Vivaldi, which we are happy to do, and some audience members will come expecting Vivaldi (no matter how the concert was advertised), but find themselves content when they hear something else instead. Every so often a real Vivaldi enthusiast will say they wished we had played more Vivaldi. One individual wrote to us about our inclusion of a Vivaldi trio sonata (without harpsichord) at the end of CD Vol. 2, saying that it was not appropriate and he hoped we never did that again. Another reviewer of the same CD loved the inclusion and the way it connected the string trio to the trio sonata, remarking that one did not miss the harpsichord at all. As an ensemble we enjoy the fluidity between time periods and genres, and discovering how individual works and composers defy their categorizations.

We are an early music ensemble in that we play on period instruments and use historical information as part of our performance process. But whatever we do has to be relevant to an audience sitting in front of us today and in that sense we are not really different from any other kind of chamber group. Our goal is always to communicate with the audience, to invite them into our conversation, and to share all the joy and passion we feel. The last thing we want is for them to walk away saying, “Yes, that was very good historical performance practice.”

A few years ago I had a conversation with the wonderful flutist Bart Kuijken, who said he thought we all needed to go back and reread and relearn all the things we think we know. For me, the exciting part about HIP is the process of learning new tools and parameters that unlock new ideas about expression. And thank goodness we can go on doing this forever.

WETA Classical is proud to present the broadcast premiere of The Vivaldi Project’s latest recording, The Classical String Trio Volume 4, during the week of April 8.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.