One of the more original first symphonies from a composer, Gustav Mahler's entry into the symphonic world was initially misunderstood. John Banther and Evan Keely break down what made this symphony different, what to listen for, and why the journey is worth the test of patience!

Show Notes

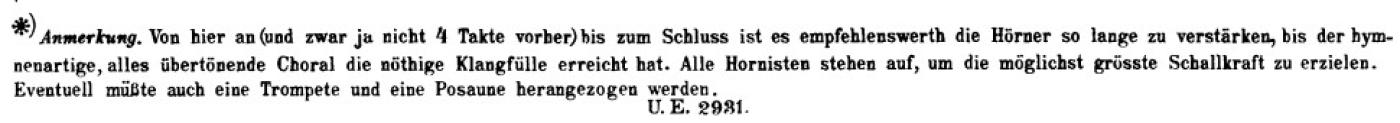

An example of Mahler's detailed direction in the score with video example!

Translation: From here to the end (and not 4 bars earlier) it is advisable to amplify the horns until the hymn-like chorale, which overwhelms everything, has reached the necessary sonority. All horn players stand up in order to achieve the greatest possible sound power. A trumpet and trombone may also have had to be used.

This moment in the music

Frankfurt Radio Symphony, conducted by Alain Altinoglu

Live (full) performance of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 1

Frankfurt Radio Symphony, conducted by Andrés Orozco-Estrada

Transcript

00:00:00

John Banther: I'm John Banther, and this is Classical Breakdown. From WETA Classical in Washington, we're your guide to classical music. In this episode, I'm joined by WETA Classical's Evan Keely, and we're exploring one of the most original first symphonies, Gustav Mowers Symphony number one. It's considered a masterpiece today, but initially it was misunderstood. We show you what sets this symphony apart, what to listen for and more. Stay with us to the end to hear some interesting quotes on Mahler, plus, we read your reviews from Apple Podcasts.

If you know Mahler, this will make sense and if not, this might help when it comes to understanding his music. You've probably heard about studies on delayed gratification, one of them being I think like when they put a kid at a table in a room and they have a big marshmallow in front of them and they say, you can eat this now or wait 15 minutes and then you'll get two. Now is 15 minutes worth waiting for two marshmallows? Probably not to be honest, but this symphony is also a test of patience in a good way. And Evan, I think it is so, so worth it.

00:01:05

Evan Keely: And that I think characterizes not only Mahler's style but the style he embodies, which is sometimes called post romantic. These very long pieces, these huge musical structures, and there really is a sense of waiting expectation that's part of that aesthetic, and Mahler really is a master of it.

00:01:26

John Banther: I like that, waiting expectation. And this symphony was quite different than other first symphonies from composers. This one might be really one of the most original firsts since Berlioz and Mahler, he was actually in his twenties when he wrote this, and we'll do an episode on his life later on, but we'll give you a little bit of a background. Now, Evan, can you give us some quick details to bring us up to his life in this first symphony?

00:01:53

Evan Keely: Gustav Mahler was born on July 7th, 1860 in Bohemia, which today is part of the Czech Republic, but in 1860 was part of the Austrian Empire. His family was German speaking and they were Jewish and he's living in Bohemia where most people speak Czech and are Roman Catholics, so you see this sense of alienation of being different somehow throughout Mahler's life, and that's a theme in his music. He also shows a very precocious talent for music from a very early age. His parents really encouraged that and he went into the Vienna Conservatory in 1875, I think he was about 15 at the time, studied piano and composition. Hugo Wolf was a fellow student there, famous for his Lieder, and Wolf and Mahler became lifelong friends. And like so many composers of his generation, especially in the German speaking world, Mahler very influenced by the music of Richard Wagner and also the music of Anton Bruckner and Bruckner was at the Vienna Conservatory at that time, and they knew each other and you see that influence throughout Mahler's life as a conductor and as a composer.

And in 1880 he completes his first big work Das klagende Lied, a work for orchestra and chorus and voices. And he also began his conducting career that year and conducting in fact would be his primary means of support throughout his life. Renowned as a conductor much more than as a composer in his lifetime, especially conducting at the Vienna Opera and the Metropolitan Opera in New York here in the United States. The symphony we'll be looking at today, the first symphony was composed between 1887 and 1888.

00:03:37

John Banther: Something very interesting here, Evan (inaudible) this symphony is so detailed, there's so much happening here, it's extraordinary that at this young age in his twenties as he's just been kind of wandering a little bit or unsure, that he has the fortitude to sit down and write something like this. So let's explore the symphony, what to listen for and everything, because there's a lot happening

Now we will try to be not so pedantic, but we already have to stop and explain the first notes. It sounds like this comes into existence from nothing. It's a very high, very airy sound, and that's because the strings are using harmonics. They are lightly pressing their finger against the string at a certain point, but they aren't pressing it down to the fingerboard. So when you use the bow, this enables the string to resonate at a much higher pitch. It also means the entrance, the articulation, the beginning of the notes aren't that precise. The sound I think is diffused, like a lampshade.

00:04:43

Evan Keely: And I love what you said John, about it's diffused like a lampshade, this whole opening to this symphony, there's this sort of weird otherworldly quality to it. What are we even hearing? Where does he get this idea, these harmonics? One of the other things you mentioned, you mentioned about harmonics and the finger lightly touching the string, which means vibrato is pretty much an impossibility too. And so there's just this sort of weird... It's like it's a computer, it's like a synthesizer, eeee, just this strange mechanical sound and this open octaves that go all the way across the span from the highest to the lowest. And it's just an incredible effect. We were talking earlier about this expectation, what's going to happen next? It catches you right away.

00:05:35

John Banther: You kind of wonder, well, what's being depicted here? We have these very soft descending fourths, this interval that gets repeated as it kind of sequences down, clarinet entrance sounds like hunting horns in the distance, followed by gentle lines and the actual horn, offstage trumpets.

Mahler was very deeply in love with nature and depicting nature and also depicting the human experience. I think you can say Mahler was quite existential. And we can even ask, well, why use clarinets to depict something like hunting horns in the distance? Why not use horns off stage? Well, maybe that's a little boring. There's more abstract art and concepts happening within music at this time compared to before. So the sounds of nature, this is growing, things are moving very, very slowly. Musical ideas are evolving longer than we have with Mozart or Beethoven, that delayed expectation you mentioned.

00:06:43

Evan Keely: Another thing that I really appreciate about this opening is there's this diffuse quality in terms of the (inaudible) , but there's also a diffuse quality in terms of the key. You don't have a lot of triads, you don't have a real clear depiction of what key we're in, you have this open octaves and the strings, and then the clarinet comes in with this perfect fourth, do do, do do, well, is this major? Is this minor? Is it... Where are we? And there's this sense of, we're sitting outside, the open sky beckons to us, maybe there's a bird in the distance. The clouds are wafting and there's this sort of timelessness about it, and we're just waiting to find out what is the composer trying to say to us? And yet we're already intrigued.

00:07:29

John Banther: Something that's very characteristic of Mahler that you don't hear in the music, but you see in the score and in your parts, he's so meticulous, as in, he writes in plain German language, in complete sentences, instructions, a lot in the conductor score and a lot in the players, in the musicians parts. I've played this and I've studied Mahler many times. Actually, this is the symphony I've played more than any other for whatever reason, nobody else writes direction for musicians like Mahler, like this. Eventually you learn all of them, but you tend to keep a guide, a glossary on hand just to be safe.

00:08:05

Evan Keely: When I was in music school all those years ago, a lot of my colleagues would joke that they wanted to take German classes at school just so they could play Mahler. Learn the language. They're almost paragraphs, these long instructions on exactly how to play things. He doesn't use Italian most of the time, he uses German and he really wants to be very clear. He has a very clear vision for what he wants and he wants to communicate that as clearly as possible.

00:08:32

John Banther: So this is a slow introduction. And as we've learned in previous episodes, that's a pretty common thing in symphonies. This is a little unusual, however, in how it is stretched out, it sets the scene and provides material for the rest of the symphony in these fragments, like those fourths.

Then we get to a moment that will come back in many ways and in so much of Mahler's music, and that is we get this kind of creeping repeating rhythm. Often starts in the low brass or the low strings specifically here, and it repeats. It's menacing, it gets higher and higher, and it's building and building, Mahler is often building up in this way. When you usually hear this, you can expect something big to kind of happen next. And then this grows into a beautiful, beautiful moment. Evan, this beautiful melody that comes from one of his songs. And again, the impact here, this is several minutes into the symphony when you sit down and listen to this, it's such a beautiful moment.

00:09:45

Evan Keely: One of the things I love about this too, John, is this building and building and building it. And I think a less creative, less ingenious composer would've been built to this huge climactic crashing, and that would've been very effective. But Mahler builds and builds and builds, were expecting this tremendous cataclysmic thing to happen and what we get instead is this folk like little melody. And this is where we need to remember that Mahler before he wrote this symphony, wrote a song cycle of four songs, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, songs of a Wayfarer. He wrote some poetry, it's his own poetry, and then he set it to music and it's just sort of a very personal journey. And as we dive deeper into this symphony, John, we'll be remembering the ways in which... This is a very autobiographical, very personal statement about his life at that time and his feelings and his experiences.

So he quotes these four songs quite a bit in this symphony, and if you listen to a performance of the song cycle and if you know the symphony, there's a lot of very familiar back and forth, it's almost like he's in conversation with himself. So where we have this buildup in this first movement of the symphony, we get to this folk like melody, and he's quoting one of the songs here. And what he's quoting is a song about walking around in the field in the morning and the birds are singing, and this young man is enjoying the beauty of nature and feeling all the joy and expectation of a beautiful day, but also this sense of foreboding that his own happiness is not really going to come to fruition. So there's a celebratory quality, there's a sense of real delight and bliss, but there's also something underneath that's much more sinister and uncertain.

00:11:35

John Banther: And we hear how that fourth motif... From the opening, it's the building block for the symphony as it starts off this beautiful melody in which the text lines up perfectly with what we hear, walking in the morning across a field, a dew still clinging to the grass. And you also hear it in non melodic ways, in very metronomic like accompaniment ways in the background, it's always very close by. This builds into something quite beautiful, a great moment, and you think there's going to be something bigger but comes back down and we repeat. He's repeating the exposition, this is the section that comes after the introduction, this was very common with composers like Mozart and Haydn, even into Beethoven's time, not always done as the 19th century progresses and we're into the late part of that, Mahler does the repeat. And actually he does it in other works too, sometimes they are very, very long repeats.

00:12:33

Evan Keely: Yes, an interesting question for conductors nowadays and over the generations, which repeats do we really want to observe? You see that with a lot of composers, but certainly with these very long pieces by Mahler. It's interesting to me the way in which he's combining some really innovative ideas into this first symphony of his, but also these very old- fashioned ideas, like repeating the exposition, going all the way back to the age of Haydn in that gesture. And yet so much of what he does in this symphony is so original and unique and unprecedented.

00:13:06

John Banther: And what Mahler is doing, he's building things up and he takes it back down, he builds it up a little more and he brings it back down. He's constantly teasing out these tension and releases, and we get to this moment again where this harmonic is being used. He distills music down into this single note or this octave of notes. The cuckoos enter the flute, comes back with this motif, it feels like we're in a different land, we're suddenly not in that field with dew in a beautiful morning, but actually we feel very alone, very lonely, it's almost not disconcerting to listen to, but there's a very real loneliness to the moment here, we're back in the forest, but really alone with just these little bits of outbursts of wildlife around us.

00:13:51

Evan Keely: And I think that's a characteristic of Mahler in general, there's this mirthfulness, but there's an edge to it, there's a sense that happiness is built on illusions and that the only thing we can really count on is our aloneness. And I think Mahler struggles with these kinds of themes, there's a despair, but there's also, as we'll see in this symphony especially, this hope that emerges toward the end, the sense of possibility that he'd never quite able to relinquish.

00:14:21

John Banther: And I love that about Mahler and that it reminds me of Tchaikovsky in some of those ways and how he depicts at times despair and other times joy, but in very different ways, but with some similarities.

00:14:33

Evan Keely: Yes.

00:14:38

John Banther: From this loneliness, we get this resolution, a real feeling of relief as the horns usher us back into this clear space, maybe a happy mental state. And from here, we start building back up to now the end of the movement. Some slight ups and downs along the way. But again, when you listen to Mahler and you start hearing a repeating line in the low brass and the strings, you know it's about to get big. The climax of this movement, and again, this is something we can't fully depict here, after you've been sitting for 15 minutes listening to it, it is so rewarding, it is so gratifying.

Mahler's use of the horns section is extraordinary, there's no real other way to put it. He is a favorite for many. I feel so sad that Beethoven didn't get to hear the horn played this way, not just as a section with these huge heroic lines, but also aggressive trills at fortissimo that add a very shiny brilliance to his music. I love the color that Mahler brings and how it's very, very bright and effervescent, but still has a lot of a low end to the sound too.

00:16:07

Evan Keely: One of the great things about Mahler we see from this very first symphony is he has such a mastery of being able to convey what's in his imagination through the palette of the orchestral colors, and to use the instruments in ways which were very often quite innovative, quite challenging for the players of his era. But players nowadays, you'd go to an audition for an orchestra, many a brass player has had to play Mahler excerpts, as you can attest, John, and he has just such an ingenious way of handling the instruments as individual instruments and in these groupings and the orchestra as a whole.

00:16:53

John Banther: And also with Mahler, reminding me again of Tchaikovsky in a similar way of how he uses contrasting motion, how some lines are going up, some are going down. With Tchaikovsky it can feel very linear, lines going up and going down, crossing like a perfect X or something. Mahler, sometimes it's like a bowl of spaghetti is thrown on the floor and things are swirling all around and passing through each other.

00:17:17

Evan Keely: And yet it's not... I think that's a great description, John, but it's not just arbitrary chaos.

00:17:23

John Banther: No, no.

00:17:24

Evan Keely: There's a method to the madness. But there is madness.

00:17:27

John Banther: You might think after hearing this movement that, well, people must have loved this symphony as much as we do right at the premiere, they must have loved it. But that did not quite pan out, did it? People did not, maybe even understand this when they first heard it.

00:17:40

Evan Keely: Yeah, he's really doing something quite new here. I think part of the idea is there's some confusion about what he's trying to say both in a musical sense, but also in a literary sense. And early performances of the symphony actually had a program that Mahler shared with the audience. And John, you've been comparing this to Tchaikovsky in some ways, I find that's fascinating to compare this symphony with Tchaikovsky's sixth symphony that you and I did an episode about a while back, and Tchaikovsky had a program for the sixth symphony, but he wouldn't tell anybody what it was. Mahler had a program for this symphony, which he did share, but then as the years went by and subsequent performances, he took that away.

And I find that a really fascinating puzzle. What was he trying to reveal or change about how this work would be understood? So I suspect that was part of the confusion that audiences experienced with this work. What is this guy trying to say to us? What's this whole elaborate story that he's adding in the program notes, what did they mean? Is this just this narcissistic young man having an ego trip? And of course, the musical style and the structure and the instrumentation are all filled with these things that are novel. And I think audiences on some level weren't quite ready for this very creative way of expressing symphonic form.

00:19:02

John Banther: I think you're right about that. And we're going to put on the show notes page, some of what Mahler wrote and described it, because when you look at this and how it would've been built in a program, it's got like part one and then different points about it. Part two, there's a movement that he calls Dall'Inferno al Paradiso and... If I just looked at this, I would have never guessed this was Mahler. I would think, oh, this is some Franz Liszt piece. He also made changes not to just how he described the program or listed... In a literal program, Evan, right? He took out an entire movement itself, Blumino or Blumine, and eventually after a couple of performances, he took it right out. And I think that was a good choice.

00:19:42

Evan Keely: I agree. The five movements, it's a kind of a different thing, there's a few recordings that used that original version, just for comparison's sake, I suppose. This movement actually got lost for many years, so you really get a sense of Mahler when he took it out, really just wanted to forget the whole thing. Blumine was actually originally part of some other piece, it was for incidental music for theatrical work, most of that music is also lost. So there's a sense of Mahler really discarding this whole thing. It was rediscovered in 1966, Donald Mitchell, a musical writer who specializes in Mahler, discovered this Blumine movement. Benjamin Britten gave the first post Mahler lifetime performance of it at the Aldeburgh Festival in 1967. And it's still a wonderful piece. It's a beautiful piece by itself, and I think it actually stands alone better than it does as part of the symphony.

00:20:38

John Banther: I think so too. And that brings us to the actual second movement of the symphony. And right from the opening, again, I think we hear already another pattern, some similarity here, an interval, the fourth. So Evan, tell us about this one because it seems like it also comes from a previous composer. He did something like repeating that exposition that was more classical, and now it sounds like he's taking something from maybe Haydn.

00:21:04

Evan Keely: Yeah, so you go back to the Haydn era, usually very often the third movement, sometimes the second movement is Minuet and Trio. This goes way back to the Baroque era, Haydn adapted it for the symphony. You look at the symphonies of Beethoven and so forth, and the (inaudible) that evolved out of that, with the symphonies like Brahms or Bruckner, and Mahler is taking this really rather old- fashioned form and making it the second movement of his symphony. So the form itself is not anything particularly innovative and the melody that we hear at the beginning, these fourths, like you said, John, this triad almost like a (inaudible) , bumpa bumpa, bum, ba ba ba bum. There's this rustic quality to it, and I think what Mahler is doing here is replacing the Minuet with a Landler. And we don't often hear that term today. The Landler is kind of a rustic dance in central Europe in the late 18th, early 19th century, kind of a precursor to the waltz. And there's a waltz like quality here. So I often wonder if Mahler is replacing the very elegant Minuet with something that's a little bit more rough around the edges. And you definitely have this kind of rustic quality to this music.

00:22:17

John Banther: Rustic. That's a good descriptor I think for this, that really resonates for me. Rustic. There's also, again, points in here for the horn, Mahler loved the horn. And you may not even quite recognize the sound, they sound very nasally, very bright, very... It's just a very different sound. And what they're doing is, they're playing stopped. And that is, they aren't just... Well, when you see a horn player play, they have their right hand in the bell for various reasons, but it's not completely plugging up the bell. Here if you're stopped playing, they completely block the end of the bell with their hands so no air's really coming out, and it creates this very, very nasally sound, and it adds a very bright texture and tamper to Mahler's music. Reminds me of a certain percussion instrument, the one you, I forget what's called, you swing it around and it makes that sound.

Well, we're probably hearing it now, I'll add it in later. But I love that moment and how he uses horns. He's writing in some things into parts that you really notice when you go to see this in person, like telling instruments like clarinets or oboes to point the end of the instrument, the bell, up out towards the audience so the sound is going directly forward instead of more down or around it I guess. This is something that you'll find... It does predate Mahler, but it's in a lot of his music and it's still in use today, particularly in things like marching band, believe it or not.

00:23:44

Evan Keely: I think that Mahler would've loved today's marching bands. There's a theatrical quality to this music. And one of the things I find interesting about that, like you said, John, it's not something that originates with Mahler, but he writes, (foreign language) lift up your bells in these wind parts, puts an exclamation point in the instruction.

00:24:07

John Banther: Do it now.

00:24:07

Evan Keely: Why is there an exclamation? He really wants to make sure we know to raise those bells gosh darn it. And there's just a marvelous quality to that that I find so delightful.

00:24:16

John Banther: I can't think of anything written that I've played before 1990 that has an exclamation point in it, in the (inaudible) , that's unusual. What's also kind of confusing is that it sounds like the movement ends right in the middle of it. Before we go to a slower or a more soft section, it really sounds like the end of the movement maybe lining up in a way that he thought of with his original program.

00:24:44

Evan Keely: But this is the classic Minuet and Trio form. So you could say, this is the Trio and this is the middle section of this dance movement and suddenly much more elegant, I think John, this opening section is really kind of rough, and then this is almost smugged to me in it's refined quality and it's a little disconcerting to go from the raucous horns of the first section to this more dainty kind of musical quality. And yet it works.

00:25:16

John Banther: Yes. And this entire section, it's brought in and it's brought out by the horns. I find that interesting, maybe something more with nature. Of course, that instrument really associated with nature. And of course we know Mahler, maybe this whole trio section was a daydream itself before we get back into the dance. And one more point on this is that while this is wild and there's a lot happening, there's also a lot of stylization in Mahler's music. I think we for surely play his music better today than he was able to get from orchestras in his own time. Michael Tilson Thomas here with the San Francisco Symphony, really able to place notes, slightly adjust the tempo, moving things faster or slower. I mean, if you think of a viennese waltz, traditionally, those aren't even played in the exact strict metronomic 1, 2, 3 time. Too much to explain for now, but there's a lot of stylization and a lot of control conductors need to really, I think, make this movement and his music in general come across and it's done brilliantly here.

00:26:26

Evan Keely: Yeah, I agree with you John. This Michael Tilson Thomas San Francisco Symphony Performance is really exceptional.

00:26:33

John Banther: And we'll get into the next movement right after this.

Classical breakdown. Your guide to classical music is made possible by WETA classical. Join us for the music and insightful commentary anytime day or night. You can stream the music online at wetaclassical. org or in the WETA Classical app. It's free in the app store.

Now it's time for the third movement. Evan, one that probably upset audiences the most, one that I really, really love. It opens with the Timpani. And what are these intervals? They're fourths. The Timpani is going 5- 1, 5- 1, but it's still that interval of a fourth and possibly inspiration for this coming from this illustration or drawing from (inaudible) It's basically a funeral procession of a hunter, but all of the procession is made up of animals in the forest,

00:27:39

Evan Keely: Right, there's this very sarcastic sardonic kind of quality to this. Whether or not he was actually... Mahler was inspired by this image or something like it, it's a little hard to be sure, but this whole thing has this sort of bad dream quality about it, but it's so compelling even for, like you said, that bum bum bum, the one that (inaudible) fourth with the Timpani at the very beginning. But then we have this really remarkable solo instrument right here, don't we, John?

00:28:06

John Banther: Yes. The double bass comes in, very big audition (inaudible) bass and some of the instruments that follow, then the bassoon comes in, then the cello, then the tubo. It's Frere Jacques in a minor key, and it is very eerie as... They're passing this line off, but it's not one completely finishes and then the next, there's overlap between these and they slowly grow more and more together. Almost like the procession, if you want to think of it this way, of these animals going through the forest, carrying this hunter, whatever, funeral, there's more joining in as it goes along. And then by the end, you're seeing it go off in the distance. If I was an animal, I don't know if I would be part of that. He's a hunter, he can take himself, leave me out of this.

00:28:58

Evan Keely: Well, but there's this really edgy equality to it though, isn't there John, this song, oh, we're so glad that he's dead. Whose funeral is Mahler actually thinking about here? There's this really kind of horrifying quality to this that I find... It's a very dark joke. It's interesting too, to note in this whole section, we were talking earlier about how specific Mahler is in his verbal instructions in the score, and he's very careful at the beginning of this whole movement to write, all voices are to be pianissimo without crescendo. So there's this kind of stifled quality. We can't speak above a whisper ever for this whole section. And it's like the joke is so naughty, it's so inappropriate to make this ghastly morbid joke that we don't want to say it too loudly, but we can still hear it and he still wants us to hear it.

00:29:54

John Banther: Something we also hear in his music, this (inaudible) band moment in the music, I love this and it'll come back later, but this slowly starts to deconstruct from this Frere Jacques moment in time down to a single note. Basically he's distilling it all back down and then out of that grows something new, the harp rises out of it and then we get this gorgeous melody from one of his other songs.

00:30:38

Evan Keely: This Is another quotation from the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, the songs of a Wayfarer. And in this section, he's evoking a song in which... Again, the poetry is by Mahler himself, and he's imagining sleeping under a tree and finding this... Seeking out this spirit of restfulness that's eluded him. So there's this beautiful tranquil quality to it. But again, underneath that is the sense of unfulfillment.

00:31:09

John Banther: It feels like the smallest, tiniest bird, the littlest melody you can hold in your hand, it's just for you in a little box, you can look at it whenever you want, just for you. I love these intimate moments.

00:31:21

Evan Keely: I feel the same way, John. There's this kind of fragility to these little melodic fragments or these moments of exquisite beauty that come out of this uncertainty or this despair. And then there's this something that's so precious and lovely and it's like a bird, you're afraid it's going to fly away,

00:31:39

John Banther: But almost like a Hitchcock or Poe, terror is just right around the corner, something very unsettling. This moment as the march comes down, entrance with the tamtam and the bass drum, and actually he even writes in the music, there's this long note for the tuba, if the tuba player cannot play this precisely at this dynamic, very soft, have the contrabassoon play it. So he is trying to control the sound here. We've had so many transitions where it distills down into one note, here it's just silence.

And then a horror movie where it's like Freddy Krueger or Michael or something just walking towards you with a knife, Halloween, it just comes back in and it is so terrifying.

00:32:28

Evan Keely: And the weird thing here too is he raises it a half step. So the thing starts in D minor, and then when we have return of this funeral march melody, it's an E- flat minor, very strange key-

00:32:42

John Banther: Very intentional.

00:32:42

Evan Keely: ...and a very strange tradition.... Yes, he knows exactly what he is doing. And then we have this transition from the third movement to the finale, and Mahler does something in the score here, which I find really fascinating. It's not unusual in a multi movement work for one movement to go directly into the next movement without any pause. And Mahler indicates that in the score, he says the fourth movement is to immediately follow, but he also puts a fermata, a hold sign on the double bar at the end of the third movement. So there's this long pause and he says, go on to the next movement, but he also wants a long pause there.

So what the heck is it? It's like this paradox, go on, but don't go on. What do we even do there? What is a conductor supposed to do? I think a lot of conductors probably don't lower their arms, which is a kind of a non- verbal cue to the audience that that's where they can clap or cough or whatever. And then all of a sudden, this fourth movement finally kicks in, it's the longest movement of the piece, both in terms of time and in terms of the sheer number of measures. And we have this whole long journey to go on before we can get to the end. And from this dying out at the end of the third movement to this fiery storm at the beginning of the fourth movement, it's just an incredible effect.

00:34:06

John Banther: And the effect is so striking when you think of these outer movements, the first one starting almost as diffuse as possible, this one starting with an extremely pointed articulation. And part of the stormy feel here is how Mahler is using the violins, what he's writing for them right away in the opening. He's writing rhythmically and in a (inaudible) like effect. And the tempo, the beats aren't getting faster, but the number of notes per beat is increasing, it gives us very... a wind swept sound. And this goes on, and (inaudible) tossed around. And from that emerges this extraordinary theme.

It's an incredible... Imposing, very, very direct theme, a type of theme we've really not gotten quite yet in the symphony. And there's this great quote, Evan, that I found in several program notes, I can't find the actual source for it, but I'm seeing it all over the place. So take it with a grain of salt, maybe this was from the description he had done in the paper before, I think the first premiere, but allegedly Mahler wrote this saying, the hero is exposed to the most fearful combats and to all the sorrows of the world, he and his triumphant motifs are hit on the head again and again by destiny. Only when he has triumphed over death and when all the glorious memories of youth have returned with themes from the first movement, does he get the upper hand. And there is a great victorious corral. And this lines up exactly with the music I think as we'll see.

00:35:51

Evan Keely: I couldn't find the source of that quote either, John, but boy, it's... Yeah, grain of salt I think is appropriate. But whoever said that, and it may have been Mahler himself, that does in fact give us a pretty darn good description of what's happening here.

00:36:06

John Banther: Another thing you can listen for in Mahler's writing, towards the end of this opening section, again, it's so fast and it seems inconsequential, but it really isn't, he writes swelling lines in the brass lines where they just just amp up really quick. It sounds deceptively easy and simple, but it takes an inordinate amount of time to actually get this under control and really play this correctly when you're studying your instrument, it takes years to fully master and control the instrument just as you can easily, I don't know, put butter on toast or something.

00:36:41

Evan Keely: Mahler really demands precision from individual players and from whole ensembles. And yeah, I think in the 1880s when musicians were not used to these kinds of demands being placed upon them, the sound may not have been the most satisfying. But fortunately, orchestras today are steeped in this, and as you were saying, John, you really have to spend years developing these kinds of techniques to play this music the way Mahler meant to for it to be played, and we can enjoy that today.

00:37:12

John Banther: And we know Mahler takes a long time to develop things. He does a lot of tension building and then a little bit of release and the intention and then release. So it's not too surprising that from this huge storm, we actually go back down and we get this eerie, rather long tense section that is very delicate and it's very beautiful. Again, I think we're seeing a pattern here with how Mahler brings these kinds of things in.

So as this section builds and there starts to be tension, he builds it up, it reaches this dynamic and the actual release, the resolution here, it's not quite complete, it leaves us wanting, it reaches the climax actually before that resolution. And this is just more of, we got to wait for our second marshmallow. And then what's next, Evan, but a beautiful moment for the horn, one of Mahler's favorite instruments.

And then from here, something we've seen several times, what happens when we have someone coming in with this slow repeated line again and again building up, it just builds up to something quite cataclysmic in the music. But even this is short lived, followed by another theme that's introduced quietly, and this is very different I think, it brings us to the end, it's heroic and it gets huge, but he introduces it in a very... It's just interesting, it's quiet, it's very delicate. I feel like so many composers would just come out and scream it.

00:39:44

Evan Keely: Here is my theme, okay, this is the moment you've been waiting for, this is the second marshmallow, but Mahler kind of slips it around the corner almost.

00:39:53

John Banther: Yeah, I think of, you see this huge shadow coming from around the corner that looks like a lion, but it's a little mouse with a toothpick. And I want everyone to just listen to this next moment for a second because it actually comes back later a little bit differently. And although this passes by quickly, it really shows how Mahler is very clever in setting up these resolutions or climaxes, this moment builds up, then the tempo is pulled back and a little space is added in the music and it delays this expected climax.

So where do we go from here? Does it build all the way to the end at this point? No, it comes back down and it actually brings back the beginning of the symphony. We have the nature, we have bird calls, again, he's distilling it down and then he builds it back up. And for a while we get just this extraordinary moment, which I have to say Evan, is so great to see this in person, I've been so lucky to see two big orchestras do Mahler cycles and seeing this in person, I mean, it's cheesy to say it's life changing or something, but it can be quite existential being in a room with 2000 people experiencing this moment all at the same time.

00:41:20

Evan Keely: Mahler writes in the score here (foreign language) very tender and expressively sung. So we have this slow building backup, but even that is just momentary.

00:41:33

John Banther: Yeah, we talk a lot about timing or rhythm with composers and across a symphony, just like in a movie, how things are spread out across an act. And Mahler is a genius with that, as you can tell. And things are starting to build up and come back down maybe a little quicker as things are starting to amp up, although it might still be a soft dynamic, like this moment here, this moment for the oboe that is just beautiful and just hanging out there.

00:42:02

Evan Keely: And I really hear in this particular moment the influence of Anton Bruckner. I don't know if I'm right to say that, but there's this sense... Bruckner is such a master of this building and building over long phrases and long sections of music and I think Mahler is evoking that spirit so marvelously here.

00:42:21

John Banther: A lot of these moments may start to sound familiar as we're describing them, kind of in the same way at different points. And it shows Mahler's thinking as well at this point because he's able to construct and deconstruct themes from a small motif like the fourth. And then he also treats everything, maybe those little toy blocks for kids. He's able to take things down and then rebuild them. Now remember earlier Evan, when Mahler delayed that big resolution by a beat or two, giving us this suspense, this delayed gratification, listen for the change here.

I think this is so intentional, and I think it's also sneaky, you don't quite realize it even, actually, I hadn't really even thought about it too much until we started working on this episode. This is very intentional and it creates this jump of forward motion that I don't think you would quite get if we didn't have that contrast before. Now we get to a section, Evan, that I think you really only see with Mahler, and that is where he tells the horn section to literally get out of their chairs to stand up.

00:43:45

Evan Keely: He's really... There's a theatrical quality to so much of this music, we mentioned earlier that discarded second movement that was part of a theater piece or raising the woodwind players, raising their bells, Mahler doesn't fail to think about the visual aspects. You were talking earlier, John, about being present for a performance of one of these pieces, of what it's like to actually be in the room. It's great that we have these wonderful recordings to listen to, that's that's wonderful. But I think Mahler is really thinking about the physical experience of being present and having something like the horn players stand up, I think his creativity is really focused on the actual experience of being in the room when the music is being played and what that's like.

00:44:32

John Banther: Yes, it's so striking because they also stand up together with intention. It's not just like meandering like, oh I'm going to go get a drink or something. They all stand up together. You can also see in your part, bells up, which is where they literally kind of pivot and their horns kind of go in the air. The visual effect is striking as you just described. There is a sonic or an audible difference as well. One, when the bells are pointed up, they're now not pointed maybe towards the ground, into the percussion section, into other people, but now higher up directly into a wall which bounces back into the audience. So it's also really dependent on the space, how much... sonically it makes a difference. But he's also writing for the horns, that they are basically to dominate, to soar through the orchestra. And that's part of the effect here as well.

This is why people love Mahler, myself included. And that's because you sit, you listen and he brings you at the end, everything and the kitchen sink, but it's also very, very, very balanced. And the color palette for me is just out of this world.

00:45:45

Evan Keely: I completely agree. And I would add that this is a very, as we were saying, a very personal statement on the part of the composer. And one way to look at that is to say that he's depicting his experience as a young man who is trying to find his place in the world. One of the things he's struggling with is this very bitter disappointment in love. He's in love with someone and it doesn't work out, and he's heartbroken and this symphony is an expression of that.

It's very easy for those kinds of things to be mundane. These are pretty typical experiences that a lot of people have. And this could be filled with very trite, very uninteresting expressions of, oh, I'm a young man trying to figure out who I am, and it could be quite boring. And Mahler, because he is so creative, so original, so steeped in this tradition of Wagner and Bruckner, of being able to take these grand, gigantic ideas and these timeless themes, and he's able to express them in a way that's so compelling and powerful to us even today through the course of his development of ideas, the way he extends and makes us wait and makes the wait worthwhile. The extraordinary use of different colors and (inaudible) and sounds, the hinting at thematic material and then finally giving it to us in a full form at the end, it's just a very satisfying and well constructed work that it doesn't surprise me this continues to be one of Mahler's best loved works and one of the best loved works in the repertoire.

00:47:24

John Banther: And for all the reasons you described, that's why I think so many people have a hard time falling asleep after a concert of Mahler one at night with a big orchestra. It's so electric, I'm awake for a long time after a concert, I remember those nights.

Now at the end of such a long and interesting journey, sometimes it's worth looking back to where we started, the opening of the first movement, a single note played in different octaves with this harmonic technique, motifs growing from it, I think you get the idea of how everything we've been describing fits directly into this right at the opening of the symphony and how Mahler's approaching the entire thing. It's the whole world evolving from this tiny high- pitched almost squeal of a computer.

And before we finish, let's take a look at a couple of quotes that I think are better mentioned now at the end. One critic said, I think even a close friend, Victor von Herzfeld said, all of our great conductors have themselves eventually recognized or proved that they were not composers, this is true of Mahler also. Another critic said, we will always be delighted to see him, Mahler that is, on the podium as long as he does not direct his own compositions. In his time, he was known as a conductor, this music was bewildering to people, but here's a quote that I think maybe matters the most. Mahler himself said, my time will yet come, humanly I make every concession, artistically none.

00:48:59

Evan Keely: And he was right. He is certainly remembered as a great conductor, but all over the world, people love Mahler as a composer.

00:49:07

John Banther: Now it's time to get to your reviews from Apple Podcasts, what do we have, Evan?

00:49:12

Evan Keely: We got a five star review from Yemeksepeti on April two. This is somebody who was writing to us from Turkey, if I'm not mistaken. And this reviewer gave us five stars and said, just listened to Rachmaninoff and I was looking for a good informative podcast about his life and influences, found your podcast, and it's deliciously informative and interesting and entertaining. Looking forward to listening to the other episodes, thank you very much. Well, thank you very much Yemeksepeti, I'm sorry if I'm not pronouncing your name correctly, but we do appreciate your feedback and we'll do the best we can to keep them coming.

00:49:51

John Banther: And actually, Evan, it's funny, I looked up because it sounded a little familiar. Yemeksepeti (inaudible) , I believe that's actually the Uber Eats of Turkey, so that's also interesting. Hopefully you can order something nice to eat while you listen to Mahlers first symphony.

Thanks for listening to Classical Breakdown, your guide to classical music. For more information on this episode, visit the show notes page at classicalbreakdown. org. You can send me comments and episode ideas to classicalbreakdown@weta. org. And if you enjoyed this episode, leave a review in your podcast app. I'm John Banther. Thanks for listening to Classical Breakdown from WETA Classical.