Music was used in World War 2 like never before, from propaganda to national pride. John Banther and Evan Keely explore Copland's musical effort to rally a defense for democracy using Abraham Lincoln's timeless words and examine why it was banned from a Presidential inauguration.

Show Notes

Gerard Schwarz conducts the Seattle Symphony with James Earl Jones

Read Belonging to the Ages: The Enduring Relevance of Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait by Karylyn Sawyer here.

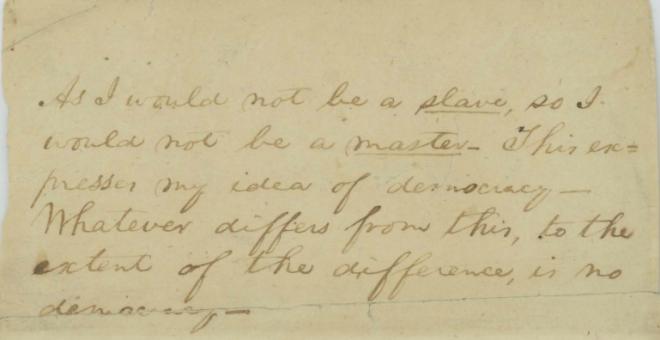

Abraham Lincoln's notecard which has come to be known as his definition of democracy

Transcript

00:00:00

John Banther: I'm John Banther, and this is Classical Breakdown. From WETA Classical in Washington, we are your guide to classical music. In this episode, I'm joined by WETA Classical's Evan Keeley, and we are exploring Aaron Copeland's timeless work, Lincoln Portrait. Looking into the music, we show you what to listen for, and find popular songs hidden within. There is also text read in the music, too. We look at what Copeland included and why, and just what kind of person is meant to be reading the part.

I think we know, Evan, that music has always been political for centuries, and we saw its use in World War II in a whole new way, I think, especially with the advent of film and radio broadcasting. And this work that we're exploring came out in 1942, so to help get us started, I think it helps to know how music was intentionally being used at this time. And so, we're actually going to be quoting from a scholarly article in this episode written by Kaylin Sawyer, it's called Belonging to the Ages: The Enduring Relevance of Aaron Copeland's Lincoln Portrait. And it's also free to read, so we'll put a link to it on the show notes page at classicalbreakdown. org. But Evan, why don't you read this quote here that I think really sets up how music was being used at this time.

00:01:20

Evan Keeley: Yeah, this article by Kaylin Sawyer, John, she's from the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, and this is a really insightful piece about this work of Aaron Copeland. Here's a quote from that article. " With Germany's invasion of Poland in 1939, the world was on a path toward global conflict. This total war would be mobilized on the battlefront and the home front, employing everything from mechanized weapons to popular music, just as Copeland had referred to music as a weapon in the class struggle. So now, 'music no less than machine guns has a part to play and can be a weapon in the battle for a free world.' The musical diplomacy of World War II aimed to rally the hearts and minds of Americans to the fight for democracy. Serious music, a reminder of civilized society, was needed to impress, to inspire, and to reinforce democratic principles. Historian Annegret Fauser contends that no event in history used music so totally, so consciously, and so unequivocally in promotion of a national cause as did World War II."

00:02:30

John Banther: That is a wonderful quote there, Evan, that I think really sets this up, because I think it's important to know this and to also understand the urgency behind it, as well.

00:02:41

Evan Keeley: And it also gives an insight into, Kaylin Sawyer writes a lot in this article about Aaron Copeland's social consciousness, especially before the war. He kind of flirts with communism and progressivism in a way that you and I talked about, John, in our episode about Aaron Copeland recently. I would say he wasn't a communist in the strict sense, but he certainly had a sensibility about class struggle, about the struggle of working people, about the struggle of everyday persons, and you see that in a work from around the same time, Fanfare for the Common Man, but you certainly see it in Lincoln Portrait.

00:03:16

John Banther: Yes, and with all of that, and with the weight of the situation that you described in that quote, you can imagine the speaker that is used in the work whenever it's performed is usually a person of prominence, a person of influence, a person of respect. And we're going to be using a recording featuring James Earl Jones, and we'll probably explain why in a little bit, but we've also seen this performed by Maya Angelou, Katharine Hepburn, and Henry Fonda, also, Coretta Scott King, and a powerful performance narrated it in February 1969, not even a year after MLK Jr. was assassinated. So the work is loosely in three sections, and the speaker is in just one of them, and stay with us to the end, as we'll also hear why and how this was scheduled for an inauguration concert, and then pulled after protests from a congressman. So Evan, it's 1942, that's when we see this piece come out, and, well, why did Copeland write this? He didn't just come up and wake up one day and say, I'm going to write Lincoln Portrait.

00:04:16

Evan Keeley: So 1942, of course, a very consequential year in American history, with the invasion of Pearl Harbor in December of the year prior. And you see, as you were saying at the beginning, John, this use of music in broadcasting and cinema, it really becomes a part of mass culture in a way that was new in that era. We take that for granted, I think, today. So during the war, music becomes one of the weapons, as we were seeing from that quote from Kaylin Sawyer, it's part of the war effort. There's the mechanized components of warfare, building weapons and ships and so forth, but also, mobilizing the populace in terms of the hearts and minds of the people, and this work of Copeland's is very much in that context.

00:05:02

John Banther: Yes, and it was conductor Andre Kostelanetz, who was moved in 1942, there's a quote that he gave in Time Magazine that's also in that article we're quoting, saying, " I want people to get the message of what democracy is, what we are fighting for." And so, after this attack, he sought out to commission three works to, quote, " represent a musical portrait gallery of Great Americans." And interestingly, I found out that Lincoln wasn't actually Copeland's first pick, I didn't know this, it was actually Walt Whitman that Copeland chose at first, but then, someone else, Jerome Kern, who was commissioned, he selected Mark Twain. So then, Kostelanetz goes to Copeland and says, hey, why don't you pick someone else, maybe a statesman?

00:05:49

Evan Keeley: Right, instead of another literary figure. And you and I talked in the Copeland episode about his enthusiasm for Emily Dickinson, so I also didn't know he was thinking about a Walt Whitman portrait, which also might've been quite interesting, a great poet, to be sure. Copeland had a great taste for poetry, I think. So Mark Twain becomes the subject of Jerome Kern's work, and Copeland is trying to find somebody else, and Lincoln becomes the figure that he turns to, to be the subject of this new work.

And Copeland explained later on, Lincoln was a favorite during the war years. Furthermore, I recalled that my old teacher, Rubin Goldmark, had composed an orchestral Threnody in 1918 entitled, Requiem Suggested by Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. So in reflecting on this commission, Copeland would go on to write, " from that moment on, the choice of Lincoln as my subject seemed inevitable." So I think that's really interesting that at first, this wasn't his first thought, but then, as he makes a commitment to it, he becomes a lot more enthusiastic. And I think that as we listen to this music, we hear a real commitment on the composer's part to the subject.

00:07:11

John Banther: So let's go to the music, this opens in a way that we also learned about in our episode on Copeland's life and his music. There is a sense of a large canvas here, there's large intervals, there's a sense of space, there's these calls in the winds, but although it feels serene, Evan, there is something different about it, there's a dignity, a larger purpose. This is a melody, this is a moment in the music, the music is not slouched over.

00:07:38

Evan Keeley: Yeah, there's that double dotted rhythm you hear a lot, dum, duh, dum, dum, duh, duh. If people aren't familiar with what that, double dotting is when you have a rhythm like that. This goes way back, in my view, to, you can think back to the 17th century, like a French opera overture, that was written to glorify Louis XIV or some stately thing. And something about that rhythm, dum, duh, duh, dum, duh, duh, to me, that just kind of speaks to, it's a musical language of human dignity. It's something that, it conveys a sense of importance and profundity. And Copeland uses that, I think, so effectively. You hear that rhythm throughout the piece, it's almost like a rhythmic leitmotif throughout the work. I don't know why it has that effect on the human brain or the human heart, but it does. We certainly experience that in Lincoln Portrait.

00:08:31

John Banther: It goes back to the trumpets announcing the king walking in, dun, duh, duh, duh, duh, duh, dum, and it's literally where we get the ta- da, from when we say ta- da. We use that a lot in music, like in brass playing in rehearsal, when you have to play these things, we talk about making it snappy, not making it kind of lazy like a triplet. And ta-da, ta- da, there's a very snappy effect to it, and it's that kind of trumpet (inaudible) calling of introducing the king. But it's not introduced with a trumpet here, it's introduced in the winds, but strings come in later, and it creates some anxiety, and it gives more ... It makes me think more, Evan, about what the purpose of this is in the music. Is it about dignity? Is it the melody? Is it the music not being slouched over? Because we get to quite a large scale several minutes into it, and we haven't really had a melody yet.

00:09:28

Evan Keeley: Yeah, you're right, there's not a clear set of melodic line, and there's a sense that I feel where there's this very dignified expression, but there's also a sense of something being ... There's a sense of unease, and there's ... Of course, the context is war and struggle and uncertainty, and the struggle to preserve democracy. We were talking about Lincoln in the early 20th century, and in the minds of Americans, and in World War II, you really see this national idea about Lincoln coalescing around this themes of patriotism. Lincoln, of course, the wartime president, democracy under threat, will the nation endure? And Lincoln becomes a kind of patron saint of freedom and American idealism during World War II, and I think the sort of the uneasiness that we hear in these opening minutes of Copeland's Lincoln Portrait are trying to reach into that and convey that sense of struggle.

00:10:25

John Banther: If I was in the concert hall, I imagine I would be sitting up in my seat.

00:10:29

Evan Keeley: Yeah, it's not relaxing music.

00:10:31

John Banther: No, no. But then we get a solo in the clarinet, and this is also a Copeland- esque thing, I think, when he's got to a moment and it starts to diffuse. And instead of going to something like a brass instrument or something else, or even like a cello growing out, he grows out with a wind instrument, and he does it on a folk tune. There's two folk tunes that he's quoting here, and the first one is, on Springfield Mountain. It's this folk tune about a young man bitten by a snake, and then dies, but it's beautifully brought out here in the clarinet in a very solemn type of way.

00:11:24

Evan Keeley: Yeah, there's that wistfulness, and of course, it evokes in my mind, as it does, I think for many of us, the opening of Appalachian Spring.

00:11:32

John Banther: Also, when I hear this music, it reminds me of the Lincoln Memorial, that's kind of an obvious thing to say, but also-

00:11:38

Evan Keeley: Sure, sure.

00:11:38

John Banther: ... the architecture at large here in Washington, the brutalist aspect of it, I find that in Copeland's music.

00:11:45

Evan Keeley: Brutalism, but also that neo- classicism that you see in a lot of the architecture in this city, that sort of larger than life grandeur. And yeah, I think Copeland is definitely ... Like we said, the Lincoln Memorial was completed in 1922. This is a pretty recent memory by 1943, and this idea of Lincoln as this, literally, a towering figure, but also figuratively, and I think the music is really reaching for that idea, and I think conveying it quite powerfully.

00:12:17

John Banther: And then, a trumpet solo appears. And it sounds like it's coming from the background or far away, it's kind of distant, and it's that On Springfield Mountain folk tune being brought in. But there's also something else here, Evan, and that is, for me, I hear him evoking Taps.

00:12:43

Evan Keeley: Yes.

00:12:44

John Banther: And Taps is something, for Americans, that's an immediately recognizable signature that we know that's used in-

00:12:51

Evan Keeley: Fallen hero, the dignity of that moment, the solemnity of it, yes, definitely, definitely hearing that, too.

00:12:57

John Banther: ... Because we all die, that's not special, and we're not going to have Taps played at my funeral or something like that, because there's something else about it, what you're talking about there, and also, the honor and the dignity and the sacrifice that we put on there. So I hear this uplifted, solemn, and also, looking forward moment here that is quite affecting. And then, Evan, we get to the second of three sections of this piece, and reminds me of something else about Copeland we learned in that episode about him, and that is, he assembled materials, that's what he said. He said-

00:13:38

Evan Keeley: That's what he said, yes.

00:13:38

John Banther: ... Yeah, not composing necessarily always linearly, but assembling, so we have this very quick transition to what sounds like another folk tune.

00:13:48

Evan Keeley: Yes, it sounds like Camptown Races, which we think of as folk music, it's actually Stephen Foster who, how much of that was original music and how much of that was with him drawing on a folk idiom is a fascinating question to musicology. But Camptown Races, (inaudible) , we kind of have an echo of that. It's not quite that tune, but very, very similar to it, and you can't help but be sure that that's very deliberate on Copeland's part. And of course, the history of Camptown Races, published in 1850, is so complex and so indicative of the contradictions and ironies and struggles of American life, this very sort of innocuous sounding thing, and yet, there's this undercurrent of racism and inequality and injustice that's embedded in that music. And of course, Copeland, who's so conscious of social issues, is surely aware of that, and is he challenging us to think about that in an unconscious way? I'm not really sure, but it's a very loaded moment that could sound, to the untrained ear, rather innocuous, but I don't think that it is at all.

00:15:03

John Banther: I think so, too, it's a minstrel song, and one that has remained acceptable within culture, one of the most popular tunes from this of that time period, but this does become a bit ironic when we get to the text later in the music. So what are we thinking here, Evan, with these two sections? There's probably several ways to think about this and listen to this. Is Lincoln charting off in life? Is it rural, and then, city Lincoln? Is he arriving in New York, getting off the bus, going to Broadway?

00:15:39

Evan Keeley: Yeah, I mean, there's a sense of (inaudible) energy in the music, is it portraying Lincoln as this decisive man of action, the young lawyer who goes to Springfield to start his career in law and in politics, and he's struggling and renting out these cheap rooms and eating bad food in order to move forward his career and live the American dream? I don't know, but there's this energetic phase of the music here that, I'm not sure what exactly it's trying to say. But again, as you were saying earlier, John, it makes you want to sit up in your seat.

00:16:13

John Banther: And part of the energy, I think comes from a bunch of fragments that get brought out in the music by several different sections. And we have solos everywhere, from oboe to trombone, and then we get a mixture of those two tunes, the Springfield Mountain, and then, Camptown Races. And it feels like we get to a point that is very American within music, with the xylophone, the whipping strings, it sounds frenetic, but it still sounds very heroic at the same time.

00:16:55

Evan Keeley: And that Copeland optimism that you and I talked about, John, in that episode about Aaron Copeland, you really see that in this music, even though there's also the undertone of struggle and uncertainty in the war, but that sense of the possible, that sense of optimism, and how that must have sounded to the audiences that first heard this music, that sense of, we can do it. There's that image of the woman riveter with the bandana on her head and flexing her arm, we can do it. And I'm really hearing that spirit in this part of the piece.

00:17:31

John Banther: Yes, the optimism, I think is key here, all the struggles and things you're talking about, but still, Copeland believes that there is a path forward. So this goes on for just a minute, and then it slowly coalesces into some of the low instruments, like string bass and contrabassoon. And then, we get to our third section where the speaker now joins in, this is the third section, and let's just listen to how this starts.

00:17:58

James Earl Jones: " Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history." That is what he said. That is what Abraham Lincoln said.

00:18:19

John Banther: The way that Copeland introduces us to the speaker and introduces us to Lincoln is quite specific, and it sounds like it's intentional and related to his Jewish identity. The way this is framed is found in Hebrew (inaudible) in the Scriptures, and he spoke saying, and there is a great quote from Kaylin Sawyer again in that article that explains this. She writes, " Copeland connected the Lincoln quotations with 'narrative passages' simple enough to mirror the dignity of Lincoln's words."

She continues, " the simple narration added by Copeland employs the redundancy of Hebrew syntax. Copeland's phrasing, this is what Abe Lincoln said, he said, echoes the repeated emphasis on speaking found in the Hebrew Bible, and God spoke, saying. Using simple ritualistic syntax to frame Lincoln's words is further evidence of Copeland's imposed simplicity in Lincoln Portrait. This phrasing would be appreciated by a wide audience as a reflection of their common religious language. At the very least, this syntax suggests that Copeland may have viewed Lincoln in biblical or godlike ways. Through these words, Copeland hoped to inspire Americans to face the moral and political challenges of their time." This is such a simple thing, I mean, he's using, Copeland, that is, text and quotes of Lincoln, but how you set that up really changes how the impact is made.

00:19:49

Evan Keeley: Yeah, he could've just had Lincoln quotes, rather than saying to us, having the narrator say to the audience, this is what Abraham Lincoln said. But Copeland inserts that. That's Copeland's work, those are Copeland's words. And they're very simple, like Kaylin Sawyer is writing in that article, and I think the recognition of how that echoes the syntax, the idiomatic language of Hebrew Scripture, and he said, saying. You see that all the time in that language, you see that all the time, you look at a translation like the King James Bible, that Americans would know, sitting in the concert hall in 1942. And again, it gives it this sense of this sort of biblical proportionality, the sense of eternity, the sense of something that is of everlasting import that's being expressed in this very simple, linguistic manner.

00:20:42

John Banther: So now we'll continue with the actual quote that Copeland uses, and this is from a annual message to Congress, December 1, 1862. It's like what we call our State of the Union today.

00:20:57

James Earl Jones: Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance or insignificance can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation. We, even we here, hold the power and bear the responsibility.

00:21:44

John Banther: The words combined with the music have such an impact. The fiery trial through which we pass, also noting that, it's the trial through which we pass. We're not choosing to pass through this, this is what we're going through, either in honor or in dishonor. We here, also thinking as he's talking to Congress, but also, we here in the concert hall, hold the power and bear the responsibility. I feel like he's specific with these words, too.

00:22:11

Evan Keeley: And there's a real powerful political statement in all of this, which is assuming that both the Civil War and World War II were struggles to preserve democracy. Now, I would agree with that personally, and a lot of us would, and that's not a universal or inevitable conclusion. And this is very much in line with Copeland's perspective on American life and the role of the composer in public life, and he is very conscious of what he is saying in this opportunity to express himself to the nation in the midst of this existential crisis.

00:22:53

John Banther: And there are a couple of ironic things to this piece. One, using a minstrel song in this way, but also, the lines, we cannot escape history, also because there's people sitting in the concert hall listening in 1942 while there are soldiers off fighting for them for the preservation of democracy, as they're saying. But when they come home, they will be met with, of course, segregation, they will be left out of the GI Bill, black soldiers were not pushed up into the middle class like so many were.

00:23:22

Evan Keeley: Right, the GI Bill and the New Deal and segregated units, this is before Truman desegregated the troops. So yeah, ironies abound, and we cannot escape history has a very powerful meaning in that context.

00:23:38

John Banther: And after each quotation of something, like of that address that Lincoln gave, there's a kind of musical response within the music, like reflecting on what we just heard, letting it absorb, also, response to it, before we go to the next quotation. And so, the next one also begins with a little bit about Lincoln. And that's how each one starts, the first one was just introducing Lincoln, and now, we have this.

00:24:08

James Earl Jones: He was born in Kentucky, raised in Indiana, and lived in Illinois.

00:24:19

John Banther: So before the next quote, he learned where he was born, raised, and lived, and there is a type of mood being portrayed in the music, too.

00:24:30

Evan Keeley: Yeah, the strings in the solo oboe, I think create this sort of nostalgic mood, but also, a spirit of reverence.

00:24:37

John Banther: And we'll go to now, the main quote, this is also from that December 1, 1862, addressed to Congress.

00:24:47

James Earl Jones: The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion, as our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then, we shall save our country.

00:25:19

John Banther: Although this is from the same annual address, Evan, musically, this is more fiery than the opening quote we had, which I think had more of a droning accompaniment. Now, that double dotted dum, duh, dum, duh, dum, that is growing. It's filled with purpose, the words, our case is new, we must think anew, we must act anew. It's this call to action, literally to Congress, and then, it feels like for us listening, it's directed at us, too.

00:25:46

Evan Keeley: Yes, very much so.

00:25:48

John Banther: The third time the speaker comes back in, they describe Lincoln as he was physically.

00:25:55

James Earl Jones: When standing erect, he was 6'4 tall, and this is what he said.

00:26:03

John Banther: And Evan, of course, it's still important, before each quote, we're still getting, and this is what he said, really framing, again, that whole biblical or godlike way that Copeland's elevating Lincoln to. Something to listen for through all of these are how the musical accompaniment changes, or how it compares. I think we hear the timpani come in with this next bit, which is actually from the last joint debate with Stephen Douglas. This was in October of 1858.

00:26:36

James Earl Jones: He said, " It is the eternal struggle between two principles, right and wrong, throughout the world. It is the same spirit that says, you toil and work and earn bread, and I'll eat it, no matter in what shape it comes. Whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle."

00:27:18

John Banther: I think this is the only one, Evan, that has kind of a stormy timpani introduce it as it literally opens with the eternal struggle.

00:27:27

Evan Keeley: Yeah, the timpani kind of has a bookend quality with this section. The timpani begins it, there's a kind of ominous quality to that, and then, concluding the section, you hear, again, this very percussive rumbling, and it gives a sense of the gravity of what's being said.

00:27:46

John Banther: And what's being said is quite strong, you will work, you will toil, you will earn the bread, I will take it, I will eat it. It's the same tyrannical principle. And in the music, that rhythmic motif that you mentioned was a leitmotif, it really is, it's slightly changed, isn't it? It's no longer ta- da, like landing on that downbeat, now, it's like Taps.

00:28:09

James Earl Jones: It is the same spirit that says-

00:28:11

Evan Keeley: Yeah, it becomes even more emphatic.

00:28:15

John Banther: It's like also an exclamation point after each sentence or statement.

00:28:20

Evan Keeley: And again, Copeland choosing the words, why did he choose this particular passage? Is he suggesting that the fascists, the axis powers, have the same kind of quality of thievery about them, the tyrants of old, and that, in every generation, there's this struggle against those who would take from others. I think it's a very evocative choice on Copeland's part to use those words there.

00:28:49

John Banther: And quite a different quote, I think, than what we're used to with debates from the last couple of decades. You don't really get something quite poignant or really well said like this. And we'll get into the premiere of this work right after this. So let's talk about the premiere for a second, because of course, that also happened within 1942, and there's some context around that, as well.

00:29:14

Evan Keeley: So yeah, the first performance was on the 14th day of May in 1942, in Cincinnati, with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and William Adams, radio actor in that era, was the narrator. And so, in the context of that time period that was happening in that moment, Andre Kostelanetz, the conductor who commissioned the work, noted that the premiere occurred right after the Allied victory in the battle of the Coral Sea. So it's hard for us to remember, 1942, we know, of course, with the wisdom of hindsight, that war would go on for three more years, but of course, nobody knows in that moment, how much longer this struggle is going to go on.

So with the shock of Pearl Harbor and the many victories in Europe, with the Third Reich and their Italian allies, this sense of, maybe the war will conclude soon with an allied victory is a looming possibility. And there's a sense that perhaps in May of 1942, which is when Lincoln Portrait has its first performance, that the context, the mood of the nation in that particular moment might've caused this work to land in a particularly optimistic way, which, in the coming months and years, becomes quite a different set of experiences.

00:30:36

John Banther: It sounds like it was quite electric to have been there in the audience amidst that victory in the Coral Sea, and yeah, you don't know how much longer it's going to go for. And people, audiences, that is, would've been, some of them, a bit familiar with Lincoln being used in music. There were something like 17 or 20 large- scale works written with Lincoln as a subject from the last 20 years before this, and Copeland would've known that, too.

00:31:03

Evan Keeley: Copeland would've known that, and he referred to that in a quote we read earlier about his teacher, Rubin Goldmark. This is one of a number of works ... Again, we were talking about this Lincoln hagiography in the first half of the 20th century, and music is certainly one of the ways in which we see that. So Lincoln Portrait by Aaron Copeland, which is one of the few works from this era that we still remember today, is one of the many works that are musically celebrating Abraham Lincoln's legacy in some powerful way.

00:31:36

John Banther: And there are two more speaking portions left in the work, and this one feels like it's also the softest, most intimate and introspective portion, but then it changes a little bit. So we'll hear that quote that describes Lincoln a little bit, and then we're going to hear a shorter quote than the several other ones we've heard before right after that.

00:31:56

James Earl Jones: ... Lincoln was a quiet man. Abe Lincoln was a quiet and a melancholy man, but when he spoke of democracy, this is what he said. He said, " as I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this to the extent of the difference is no democracy."

00:32:30

John Banther: This is quite a quote of Lincoln, Evan, and one that we didn't know in his lifetime, and we actually don't even know when he would've of thought of that, what we just heard. It was written on a note, and I'll put a link, too, because it's quite legible, I'll put that on the show notes page. But this came from a whole collection of notes, like flashcards, almost, that Lincoln had, and was just writing down, and he was using them as a way to kind of think through things, little mental or philosophical exercises. And some of them, they have like, reasons, oh, yeah, he was writing or thinking about this at this time. We don't have anything about that specifically with this, but we've come to know this note card as definition of democracy.

00:33:21

Evan Keeley: Yeah, this is analogous to the sketchbooks that Beethoven used to write, jot down musical ideas. So yeah, we don't know a date that Lincoln wrote these words, but they've often been referred to since as a powerful definition of democracy,

00:33:38

John Banther: And the music reflects that, as well, in its response. Now we get to the last speaking portion of the work, and it's actually the only time that Lincoln is mentioned as President. Copeland introduces him as President.

00:34:04

James Earl Jones: Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of these United States, is everlasting in the memory of his countrymen.

00:34:18

John Banther: Now we're going to hear the full quote that Copeland includes, which comes from the November 19, 1863 Gettysburg Address of Abe Lincoln, and listen to what's happening underneath musically, and which instrument is being brought out, and maybe what they are conveying.

00:34:43

James Earl Jones: He said that from these honored dead, we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion, that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, and that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.

00:35:30

John Banther: I think a lot of people already have in mind, Evan, this feels like, with the trumpet underneath, playing Taps. But of course, it's not Taps, it's that quotation of On Springfield Mountain, and it carries that optimism that I think you mentioned earlier, and that looking forward, regardless of the tragic and horrors of the past, this moving forward in the music.

00:35:54

Evan Keeley: I quite agree, John, at the same time, the invocation of the last full measure of devotion in that era of terrible war surely struck a very powerful chord with the audience at the time.

00:36:08

John Banther: And the rhythmic motif, that leitmotif, is changed now, isn't it? It almost feels like maybe this is the answer, the resolution. We no longer have just ta- da, but just big, resolute-

00:36:20

Evan Keeley: And it's smoothed out in a way that conveys a sense of finality.

00:36:22

John Banther: ... And it ends quite heroically. So this is quite a work, Evan, and one that includes a speaker is something that doesn't happen all that often in music. And sometimes, a speaker is on stage because they're narrating like a kid's concert or something for Halloween, but this is different because of the weight and the seriousness that we've mentioned. I like using this recording for this because James Earl Jones felt like, and maybe still does, it feels like the official voice of the country every kid, I think, has imitated.

00:37:07

Evan Keeley: Everyone knows that voice.

00:37:11

Speaker 4: Luke, I am your father.

00:37:14

Evan Keeley: Yes, everyone knows that voice, it's a very distinct voice. And I agree with you, John, there's a distinctly American quality to that voice, he's like the voice of our nation in a way. Of course, he just died last year at the age of 93. It's so boring, it's so tedious to use a word like iconic to describe him, but he certainly is that. Everybody knows Darth Vader, of course, but he was in so many films, so many stage productions. I remember, I saw a video years after he did it in the late '70s, he portrayed another great American voice, another great American, Paul Robeson, and you really see him embodying the spirit of that great American, and in many ways, through the very distinctive voice that Paul Robeson had.

So yeah, I think that the choice of James Earl Jones, as you were saying at the beginning of the episode, John, when this work is performed, it's very often by someone of stature. Even in its day, Carl Sandburg was one of the narrators in early performances, and many other very prominent voices were used to convey this message. James Earl Jones is a particularly meaningful choice to hear this work.

00:38:31

John Banther: Yes, but it's not all without some caution, trepidation, or something when it comes to the speaker. James Earl Jones, well, first off, I thought of this as I was writing this, he's not James, he's not Jones, it's James Earl Jones, you put some respect on the name. So there is that aspect of it, yeah, it's someone of importance, and James Earl Jones does just enough, I think, with the acting and the inflection, and he is who he is, that it just works.

But some speakers have gone too far, I want to read a little bit from that article again from Sawyer. She writes, " in an April 1943 letter to Kostelanetz, Copeland remarked, from what I can gather, Will Gere must have been rather on the hammy side." She continues, " a note for the speaker was then added to the score cautioning against undue emphasis in the delivery of Lincoln's words, and instead relying on sincerity of manner. This caution was apparently disregarded in the first recording of Lincoln Portrait by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, directed by Serge Koussevitzky, with the narration by Melvin Douglas, described by critics as perhaps too passionate." And I'll put a link to that performance on the show notes page.

00:39:47

Evan Keeley: Yeah, I found that on the internet, also, John, it is a very heartfelt recitation. Who am I to criticize? One thing I'll say on a technical level is, when you're speaking and there's this huge symphony orchestra playing right behind you, there's a need to inflect very strongly, and maybe some speakers have a hard time balancing that in a way that's aesthetically pleasing. James Earl Jones, of course, being the truly great actor, obviously his voice is very beautiful, but truly a great actor, a great humanitarian, embodies that spirit so well. But we can think of many other narrators in many performances of this piece who were also very effective in the role.

00:40:28

John Banther: And another point on this, Evan, is that it wasn't always this piece viewed the same way even 10 years later, as we learned in our episode on Copeland's life, he was questioned in a Senate subcommittee hearing four hours because of his leftist views. And it was ... I'm trying to remember, who was it? It was a congressman that protested on the House floor in 1953 saying Copeland's work cannot be played at the inauguration.

00:40:54

Evan Keeley: Copeland was associated in the minds of some with communism. And as I've said, I don't think he was technically a communist, he never joined an organization that I'm aware of. He certainly seems to have leaned in that direction in the 1930s maybe, he certainly had some sympathy with some of that ideology. I would laugh at anyone who suggests that he was some kind of threat to national security.

But this was an era in which that was a real powerful controversy, and there were those who were of a certain turn of mind, we can remember some of their names today, who had an attitude that anyone who was associated with that in any way should be shunned or condemned, and their contributions to American life should be silenced, and so, in this particular occasion, Copeland's work was not chosen to be part of the program. And later on, of course, we look back with the wisdom of hindsight and recognize that that was not a wise or just decision, but we also recognized that the shortcomings of that era were not irrelevant to performance decisions and the kinds of music that would get performed or not performed.

00:42:08

John Banther: Yeah, it's a way of banning something without technically banning it. I think we'll probably do an episode in the future on Sergei Prokofiev, because that also outlines very clearly during this exact same time, how that's done. So that's Lincoln Portrait, what a work. I've never seen it live, unfortunately, I hope I get to experience that once. And if you've seen this live and you have a particular experience or thought about it, please let us know, you can send us an email at classicalbreakdown@ weta. org. But Evan, let's end with a review here from Apple Podcasts.

00:42:44

Evan Keeley: This podcast review came from DC Wright, and this person says, " John and the various co- hosts do a great job introducing and presenting music in a way that is completely accessible to newcomers, while still providing analytical nuance, nuggets of information, and introductions to less well- known composers and works that keep even lifelong fans of classical music like me engaged and entertained. Perfect balance of entertainment and education with the music of the centuries serving as the soundtrack." Well, thank you very much, DC Wright, for your review, and we always appreciate hearing from listeners.

00:43:26

John Banther: Yes, thank you, DC Wright, thank you for the five stars, that's our favorite amount of stars. And yes, thank you, and keep listening. And thank you, Evan, for, again, talking with me about Copeland's Lincoln Portrait.

00:43:38

Evan Keeley: Thank you, John. I haven't thought about this piece in a while, when you invited me onto the show to talk about it, I had an opportunity to look at it, listen to it again, and I'm reminded that Aaron Copeland was a composer who had, I think, a very sophisticated and humane understanding of how music and public life and politics are and should be inseparable.

00:44:00

John Banther: Beautiful. Thanks for listening to Classical Breakdown, your guide to classical music. For more information on this episode, visit the show notes page at classicalbreakdown. org. You can send me comments and episode ideas to classicalbreakdown@ weta. org, and if you enjoyed this episode, leave a review in your podcast app. I'm John Banther, thanks for listening to Classical Breakdown from WETA Classical.