Did a volcano erupt when he was born, what illness plagued his priesthood, and why did he write so many concertos? Join us to learn all about Vivaldi's life and appreciate the composer from a new angle.

Show Notes

Show notes

Vivaldi's Women, a BBC documentary focused on Vivaldi's time at the Ospedale della Pietà and the women who played his music

A CBC documentary looking at Vivaldi's life in music and how he was perceived by others in his time

Transcript

00:00:00

John Banther: I'm John Banther, and this is Classical Breakdown.

From WETA Classical in Washington, we are your guide to classical music. In this episode, I'm joined by WETA Classical's Evan Keely, and we are diving into the extraordinary life of Antonio Vivaldi. There is a lot to get into, like his time and circumstances teaching at an orphanage in Venice, how he helped develop the concerto, and we discuss if illness was the true reason why he stopped being a priest after just one year. Plus, stay with us to the end as we read your reviews from Apple Podcasts.

I've always enjoyed Vivaldi's music, Evan, but I think I found a whole new appreciation and respect for him after reading up more on his life and finding some great documentaries because I knew, like I think many, that he was a part of and working with this orphanage in Venice, training these young women in music. But I didn't realize just how big of an impact he had on that music program and the young women going through that orphanage as well. I mean, it became the best conservatory in Europe for a while, and then I didn't realize how far into obscurity his music fell. There's like two centuries worth of audiences that I think really didn't even know his music at all.

00:01:15

Evan Keely: And that's so true of a lot of these baroque composers, these early 18th century composers. Their music by the end of the 18th century really largely forgotten through much of the 19th century, and it's only the 20th century people are discovering, wow, look at all this amazing music. And Vivaldi too, as you were saying, John, he's... The more you learn about him as a person and the course of his career and the things he experienced, the more fascinating he becomes.

00:01:43

John Banther: So let's jump right into his early life. As you said, we don't know too much about it, but we know Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in Venice on March 4th, 1678, and he was baptized rather quickly, maybe because he was already showing signs of some kind of sickness or ill health, a weakness or something. A rumor I think we can already dispel is that it was not because this baptism... This quick baptism. It wasn't because there was a volcanic eruption nearby, scaring nurses or some kind of premonition. I've read about that even in CD liner notes. But that volcanic eruption, that took place, I think months or even a year apart.

00:02:21

Evan Keely: There's always these myths around these great composers and great geniuses of history. And it's hard to sort through the truth in the fiction.

00:02:29

John Banther: We do know though, this time and place, Venice in the 17th and 18th centuries, it was a pretty exciting place. A lot of music, a lot of festivities happening in the city on the water, music everywhere. And so it's kind of easy to see why he may have been drawn to music, especially because his father himself was a musician, right?

00:02:51

Evan Keely: Yes. And as you were saying, John, Venice was a really interesting place to be a musician and to be a music lover in the final decades of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century.

00:03:03

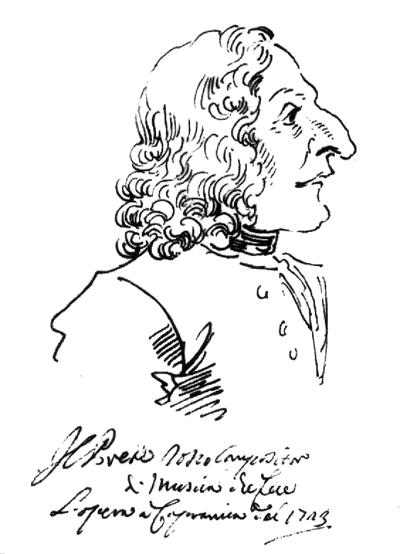

John Banther: And Vivaldi's father was a musician. He was a barber and a very well respected violinist working a lot in Venice, and he presumably gave young Antonio Vivaldi his first lessons in music, but by age 15, he starts to train to become a priest alongside his work in music. He was ordained 10 years later in 1703 at the age of 25. But after a short period of that, not even a year, I think, he vowed to never say mass again. And it seems like we have really little information to go on with this topic other than a letter he wrote 25 years later saying that he had to leave the podium or the lectern three times once during mass complaining of tightness in the chest. Asthma is something that's been thrown around a lot as an illness Vivaldi may have had. And so he stopped and he then basically, he never said mass again. But that nickname stuck, didn't it? He was nicknamed (foreign language) if I can say that right. The Red Priest.

00:04:05

Evan Keely: (foreign language) . He was a redhead and he was known as the Red Priest through his whole life. He did give up saying mass. It's not clear that he actually left the priesthood. And it seems to me that the way to interpret that is that he saw his ministry not as delivering the sacraments, but as a music minister.

00:04:24

John Banther: Yes, I think that's accurate because I've also wondered, well, how much of this is him not wanting to be a priest or as you say, share the music? Because I feel like we would've heard of more instances of him having to leave the stage or whatever as a musician. Look at any violinist leaving the stage after playing a concerto. They're sweaty. Usually there's a reason why there's, in dressing rooms and green rooms, there's a reason why there's showers in there, but we never heard anything like that.

00:04:52

Evan Keely: And lots of bottled water. But Vivaldi, a performer his whole life, and there's no evidence, as you said, John, of him having to leave the stage during a performance. And of course he wrote very athletic violin parts for himself and for the other musicians. So clearly there's a lot of physical effort involved in making this music. So I wonder. The story is that he had (foreign language) , this tightness in the chest, and we're not really sure what that means. Asthma is a plausible explanation. I even wonder if he had some kind of anxiety while he was saying mass or something, or he just felt like his calling in life was to do something different. And as you said, the duties of the priesthood maybe were less exciting to him than being a musician. It's not really clear.

00:05:39

John Banther: No, but his calling came about the same time, 1703, when he started working as the violin instructor at the Ospedale della Pieta. Tell us a little bit about this.

00:05:51

Evan Keely: The Ospedale della Pieta in Venice was part of a network of really the hospital system. Hospital is one way to translate that word, and their focus was on caring for the people in society that nobody else wanted to take care of or pay attention to for the most part. So that includes all these thousands of orphaned and abandoned children in the city of Venice. The wider network of these institutions took care of the poor and people who had nowhere else to go. And Vivaldi through his whole professional life is connected to these institutions.

00:06:30

John Banther: Yes. For decades, he's working at Pieta, and I think this is the good and bad about Vivaldi's career because as we'll see, Pieta was really the foundation of his musical life, but Pieta's existence itself was a symptom of something else in society. I mean, as you can imagine, it really wasn't a great situation for women in Venice in the 17th and 18th centuries, many turning to sex work just to, as I saw in one court case at the time, just to not starve, just to have any kind of housing or to even feed their children.

It was a very grave situation. And that combined with the tourism aspect of Venice, people from all over Europe, especially nobles, British nobles, they flocked to the city to, from what it sounds like, just to party, take in the music. And with that sex work industry, it resulted in thousands of abandoned children, many with severe disabilities because of syphilis. The boys had to earn a trade and be out of the system by 15. The girls, they got an education a bit more, and especially in music. This music program, which Vivaldi was instrumental in making something huge that also existed in part because they loved great music in churches on Sundays, these tourists who were there to begin with.

00:07:53

Evan Keely: It's really fascinating to me to think about this creative genius, and we look at his music, it's amazing. But we're also, as we're talking about this, John, we're remembering that his entire professional life, he's creating this great art and challenging these girls. They're really girls, not adults. They're teenagers or they're children. And these are people that the society in which Vivaldi lives don't value. These are not people that are valued. They're ignored. They're invisible. And what Vivaldi does his entire life is elevate them to the status of these internationally renowned musicians. He trains them to be great players. He gives them magnificent and challenging music to play. He teaches them how to play it, and he's in his whole life in these relationships of caring and collegiality with these people who most other people in his society would rather ignore.

00:08:53

John Banther: And all of this for me has really humanized Vivaldi because I think we all might have that person in our lives who was that familiar face, someone who was at your school or institution or family or whatever for decades as Vivaldi was. That familiar face that helped grow a program. I can imagine maybe the daily interactions he would have with these girls and students passing through the halls or whatever that looked like at Pieta. So it really humanized him for me, in thinking of Vivaldi more... And maybe through their eyes.

00:09:29

Evan Keely: Yeah, you wonder if he's a kind of a father figure to a lot of these girls and the way in which he's creating this great art for them and challenging them to create something that's so special and liberating and he does it for his whole life, or for decades.

00:09:47

John Banther: Maybe people caught a little bit go where we said he was hired as a violin teacher at Pieta. Today we know him, of course, as one of the great composers of this century, but he was known as one of the great violinists. Oh, and a great composer too. He was well sought after. His playing was described as astounding. He was a great teacher. He helped developed technique for the instrument. He really pushed that forward in addition to as we'll find out, him pushing forward the concerto form within the school.

So what was his first composition then, if he was busy with the violin the first part of his life? Of course, we don't know his first composition, but we have his first publication, his Opus One from 1705, two years after he started working at Pieta. It's a set of trio sonatas for violins and accompaniment.

So that was an example from one of those trios, Evan. Already for me, I don't know, maybe I'm biased or whatever. It's so fantastical. It's so simple. It's two violins and some accompaniment or basso continuo, but even there in his Opus One, I do hear a kind of fantastical, bright effervescent nature in the sound.

00:11:07

Evan Keely: He's able to compose works that are technically very intricate, and yet they have this wonderfully appealing style to them that even if you don't know anything about music, it's just so delightful and charming to listen to. But Vivaldi is not just a scribbler of pretty tunes. He's really writing in intricate and wonderful and marvelous music from the very beginning.

00:11:33

John Banther: And years later, he had a pretty big breakthrough, I think, in 1711. It was his Opus Three that was published, I think in Amsterdam. What was his? L'estro Harmonico.

00:11:43

Evan Keely: L'estro Harmonico, Opus Three.

00:11:52

John Banther: The first two publications he had were for a couple of instruments, these trio sonatas, but Vivaldi starts branching out more. We have more instruments, it's more involved. There's presumably more going on in the music.

00:12:04

Evan Keely: And this is really the second decade of the 18th century, the form that we think of as the concerto, which is we generally think of as a piece that's written for a large ensemble with one or maybe two or three solo instruments that are featured prominently. This is still a pretty new genre of music in the year 1711. And Vivaldi is among those who are actually developing this form through their compositions and through their playing.

00:12:32

John Banther: And by the time he is in his thirties, his publications, his music, it was found all over Europe. If you can get Johann Sebastian Bach interested in arranging your own music for whatever he was doing, that's quite an endorsement, I think.

00:12:49

Evan Keely: Yes. And Bach actually arranged a number of Vivaldi pieces, which gives us an indication that Bach Vivaldi's music in high regard.

00:12:58

John Banther: I also wonder how much of his writing here reflects also the space that he's in, because there's this big church or cathedral where they are playing these services or whatever, from Pieta on these Sundays. And some of the music, it sounds like you want to hear this in a place with very, very high ceilings where you hear the music directly, but then in the background above you and around you, it's kind of sparkling.

00:13:23

Evan Keely: And as you said, people came from all over Europe to hear this music that Vivaldi and his students at the Pieta were creating.

00:13:30

John Banther: He really built up that program. He gained more and more recognition and became, from what I understand, one of the greatest conservatories in Europe. Some of the best orchestras or ensembles. People, as you said, were flocking there to hear these girls play. And he wasn't writing easy music, was he? These weren't student concerts or music that was written at a more amateur level. Because for myself, even I thought for a long time, this Pieta program that Vivaldi was with, it's... Yeah, it's a great, really, really advanced kind of high school program that we know today. But no, it was a full fledged conservatory, and he was writing very difficult music and there were players there that could do it.

00:14:13

Evan Keely: And vocalists as well. And he challenged all of them to be their best.

00:14:18

John Banther: Hundreds of concertos, I think around 500 in total.

00:14:22

Evan Keely: 400 or some stupendous number. We're even possibly discovering new ones as the years unfold. But it was a... It's a vast output of music.

00:14:31

John Banther: That's something we should mention real quick is we're still finding music. I didn't realize this. In the 2000s, we're finding compositions of Vivaldi, either because they were written later in life when he was writing for private donors or patrons or just discovered in some other way. And so we have hundreds of concertos for various instruments. Most are for the violin, kind of understandable. That's really the big solo instrument of the time. But he wrote many others as well. The oboe concertos, Evan, I love these. They are so difficult, aren't they?

00:15:04

Evan Keely: He really wrote virtuosic music for pretty much any instrument you can name. And yet, as I said, as we were saying, it's technically very complex, and yet as you listen to it's just so charming and sparkling and wonderful to listen to.

00:15:21

John Banther: We did an episode on the oboe, it's number 65, and it's with principal oboe of the NSO, Nicholas Stoval. And in that episode, he's telling us how about how primitive the oboe is at this time in the 1700s. And these oboe concertos that Vivaldi was writing were so difficult. It was a couple of decades before other composers were writing at a similar level of difficulty. Players today will acknowledge that these are, they're quite difficult. So it was always kind of an enigma or wonder who was playing these concertos. But there certainly was a few girls and young women at Pieta who could pull it off.

00:16:00

Evan Keely: Surely there were some really, really gifted players under his tutelage at the Pieta. And the oboe is certainly one we've been talking about. But also the bassoon, he wrote a number of concertos with a solo bassoon, which was a pretty unusual thing even then.

So you have these very, very demanding parts for double reed instruments, which are hard enough to play. And as you mentioned, John, in the early 18th century, not as complex as they've become in modern times, so even harder to play probably back then than they are now. But clearly the girls and young women at the Pieta were able to do it.

00:16:46

John Banther: And speaking of sparkly effervescent sounds, I love his writing for the recorder or the sopranino recorder. A very, very high instrument. Takes a lot of control to play this instrument. Very unwieldy. It's almost like you're just playing a straw. For me, this is some of his most sparkly effervescent.

And of course he wrote hundreds for the violin. And this is another one of those moments, I think, with a student, that humanizes Vivaldi. Anna Maria Della Pieta was a student.... And you can imagine Della Pieta was a name shared by many of these orphans. Vivaldi was her violin teacher, mentored her. He even spent several months' salary just getting her a suitable violin. Today that's kind of a bargain, just three months of your salary for an amazing instrument. But clearly he believed in her and she was fantastic.

Eventually, she took over the roles that he was doing in charge of teaching violin as well. And he wrote several concertos for her like one we're hearing now. I mean, it shows really, I think for the violin especially, he was not... He was okay with just writing very, very difficult music because the students could do it. This one's the RV 363 that we're listening to, and we are... You might hear us say RV and then a number quite a lot. And that's because we're referring to a catalog of Vivaldi's music, right, Evan? Because I think there's got to be at least 50 concertos that are just Concerto in C.

00:18:11

Evan Keely: Right. So how do you keep track of all these things, especially if Vivaldi didn't publish so much of his music? Danish musicologist, Peter Ryom, who was born in 1937, did an enormous... Made an enormous contribution to the understanding of Vivaldi by cataloging huge numbers of his work. So when we say RV, we're referring to the Ryom Catalog or Ryom (foreign language) , in the German language. Another thing to bear in mind with these Ryom Catalog numbers is that they're not chronological. So unlike say, the Kochel numbers that we associate with the music of Mozart, if it has a 600 number, that's probably a piece Mozart wrote late in life.

With Vivaldi's, with the Ryom catalog, we don't see that. It's just as they discover and catalog works, they'll just add another number. So it can be a little confusing when you hear the numbers trying to sort out where they fit in Vivaldi's lifespan. And then we have to find out through further research and exploration where that might actually be.

00:19:14

John Banther: Because if you discover a new work and it's in the middle, what? Now, we reorder half the catalog. You can't do that. But it's really handy in that a lot of the works that I think of Vivaldi, I just remember them by the number. And it's great because when you're listening to the radio or whatever and you hear someone say, " Concerto," a bunch of different words and then RV and a number, that's all you need. When I look up Vivaldi's music and I know the number, I just type in RV 589, for example, for a work we'll talk about in just a moment. It makes it very handy.

00:19:45

Evan Keely: And you mentioned 589 and a famous Gloria, which we'll talk about momentarily, but there's also RV 588, which is a less famous setting of the same liturgical text. And when we play that on, for example, our vocal music station, Viva La Voce, I will often say, this is the less famous Gloria of Vivaldi, Ryom 588, not to be confused with 589. And as you get to know Vivaldi's music, some of these numbers as you mentioned, John, actually stay in your mind.

00:20:16

John Banther: And speaking of that, Gloria RV 589, this has become one of the most popular choral works of Vivaldi. And it asks a question. Well wait a second, we have a chorus here. There's soprano parts, alto parts, tenor parts, and bass parts in the music. This was written for the girls at Pieta. So who's singing these lower parts? Well, it was thought for a long time, kind of naturally that they were sung by male faculty members. They would just come in, sing the parts for whatever on a Sunday, and that was kind of it. But through research and everything, we found out, no, they were all sung by women. There were women bass and baritone singers.

They're not as common, but of course they do exist just as there are male sopranos. Not as common, but they do exist. So I thought that was also fascinating, and I'll put a link to that documentary on the show notes page, of performance at the school... Actually, I think, of all women singing these parts.

00:21:19

Evan Keely: That documentary is really fascinating. This is one of the more intriguing puzzles in musicology with regard to the music of Vivaldi. And for years, I was skeptical. How could women sing those low parts? But I'm convinced. It's a difficult thing to understand, but it's the most plausible explanation. There's no evidence that men were involved in these performances. There are paintings. Like you said, John, people would visit from all over Europe, some people who drew pictures or made paintings, and you see in these images nothing but girls and women performing this music. So clearly this is yet another example of Antonio Vivaldi challenging these girls and women to stretch the boundaries of their creativity and their capability as musicians. And if you think about these scores and the bass parts, which are by the way, always doubled by the instruments anyway, they are in fact by some very extraordinary women possible for them to sing those pitches. And they did.

00:22:19

John Banther: And we'll get into the next chapter of Vivaldi's life right after this.

There's another side of Vivaldi's life that takes place while he's at Pieta, and that is he gets involved in opera. This was the most lucrative, most popular form of entertainment in early 18th century Venice. It was opera. It was also considered a bit indecent, I think, or maybe risque. Something that a priest, former or not, or whatever, it's something that they probably wouldn't... Shouldn't be associated with, but he became involved and extremely successful.

00:22:52

Evan Keely: Sure. Well, that's true today too. If you're a composer and you really want to make a lot of money and be really famous, you want to have a big hit on Broadway or you want to write the score for a hit movie. And that's analogous to what opera was in the early 18th century, really throughout Europe, certainly in a city like Venice where opera is a burgeoning industry. And at the age of 35, Vivaldi tries to get in on the game, not without some success.

00:23:25

John Banther: The first one, I think Ottone in Villa, that was a rounding success, I think for his first opera. And he's 35 years old too. That's not a young age to be writing opera compared to everyone else like Mozart and Rossini.

00:23:38

Evan Keely: He's not a novice. He's got many years experience as a performer, as a musician. He's well known. He's publishing music. He's a known quantity throughout Europe, as we were saying. So yeah, this is a new venture for him. And if it's very competitive, lots of other composers are writing opera. In many cases, Vivaldi through his career is actually collaborating with these other composers. There's the tradition of the pasticcio, where multiple composers would write pieces for one operatic performance, but Vivaldi wrote quite a lot of operas through the course of his career.

00:24:13

John Banther: I think this is also another place where we can kind of humanize him a bit, just thinking about being at age 35, he's already very successful, wildly successful, you could say, as a violinist, as a composer in all these other forms. Now, there was probably a lot of expectations, I don't know, maybe pressure or something. I'm sure he had some nights where he was kind of pacing around, " Oh my gosh, what if this opera fails? Will they kick me out of this school? Will they do this or that?"

I don't know. But I think that still took a bit of bravery for him to take that on. Of course, while he's writing for opera, and he actually became an impresario, a director at Teatro San Angelo, an opera house. He continues to do that, but of course, he's also working with Pieta. He's still writing the music all the time. And it seems like maybe some of the opera characteristics bled over into his sacred music. Juditha triumphans, this oratorial he wrote in 1716 after he shortly got into opera, has some very opera like qualities to me.

The way the singer and the orchestra are working together, the sudden really short jumping out notes from the orchestra and the intensity of the voice seems a little operatic.

00:25:32

Evan Keely: Yes, oratorio of course, a dramatic form not usually staged. And it's yet another indication to me of the peculiar and fascinating ambivalence that you find in European culture in the early 18th century about opera, which as you were saying earlier, John, some people viewed it as kind of indecent or risque. You have a lot of these passionate love stories in opera, for example, and Vivaldi being a priest, well, maybe this is inappropriate, some people might have felt. And yet you have these operatic forms coming into liturgical music or in the music that you would hear in a religious setting like the Pieta, because people loved it. Everybody loves drama. Everybody loves excitement, whether or not they want to admit it. And of course, in 1716, he's writing this oratorio. This is a few decades before Handel makes the English oratorio into this huge form. But in both cases and in the cases of many of these composers of this era, you have these very operatic qualities informing the style of oratorio writing. Vivaldi was one of the first, I think, to really explore those possibilities.

00:26:45

John Banther: In a letter he claimed to write, to have written over 90 operas, only about 50 have survived. And then there's also fragments of others and stuff like that. A lot was either lost or maybe he was embellishing a little bit. I think he probably reused some stuff, but at least 50.

00:27:02

Evan Keely: Yes. Like you said, when he says 90 operas, does that mean... Does that include multiple revisions of one opera? Does it include a pasticcio with other composers? I don't know. But he did obviously compose a huge number of operas, exactly what that number is, who knows? But you discover these works. A lot of them have never been heard. We're still discovering and exploring these scores. Many of them performed in the late 20th century for the first time in more than 200 years. And so many of them are so amazing.

00:27:36

John Banther: I love that we're still discovering. I can only imagine being in the orchestra playing it for the first time, reading through it for the first time, knowing that these musicians or these instruments together have not created this piece or this music in centuries. That must be quite an experience.

00:27:51

Evan Keely: And as with his instrumental writing, Vivaldi is able to compose music for the voice that's virtuosic without sounding technical or just empty pyrotechnics. He's able to create things that are very difficult to perform, but they're incredibly exciting to listen to.

00:28:12

John Banther: Around 1718, Vivaldi takes what is apparently a prestigious position at the court of governor of Mantua. This is Maestro di Capella, and he's now, as we can see, he's spending more time outside of Venice. He's traveling, but he still maintains that relationship with them. He was paid, I couldn't find out what it was in today's dollars, but he was paid like two gold coins a month to continue writing larger works and concertos for the school as well. He did this, I guess, for many years before returning full- time, and he was visiting at times. He would come in and he would have to play and rehearse with the school, but it was 1725 before he came back.

00:28:55

Evan Keely: And he's really maintaining his relationship with other European musical centers and continuing to bolster his reputation throughout Europe as a composer to be reckoned with it. It's possible that when he was in Mantua during that time, he first became acquainted with Anna Tessieri Giro, a woman with whom he would collaborate for the remainder of his life. And she was, from what we know about her, a very capable singer, maybe not the most virtuosic, most technically skilled singer. And he wrote a lot of music for her to perform in his operas.

Apparently she was a very gifted actor. Audiences loved her. She had a marvelous, dramatic flair, many opera roles written for her. She and her sister lived with Vivaldi for many years. She traveled with him a great deal, and it's apparent that she was enormously supportive of him as a composer and as a performer. Now you can imagine, here's this priest living with these two women, and some people maybe had some doubts about whether or not this was appropriate. However, I guess, John, we have to be honest that us menfolk don't always deserve the benefit of the doubt. But that being said, there's no evidence that this priest, Antonio Vivaldi had any kind of relationship with this woman other than one of collaboration and professional mutual respect and friendship.

00:30:24

John Banther: I think all of your points there are absolutely right, and I think maybe to also bring Anna Tessieri Giro into a familiar frame today, I think it's like she was probably maybe a Broadway star. She had some kind of it factor, where she grabbed you and she had your attention the entire time she was on stage. Maybe not, like you said, not the technically most proficient, but she had something else.

00:30:49

Evan Keely: And clearly a very shrewd businesswoman and a very dedicated musician and who really understood the industry, I think in a very sophisticated way.

00:31:00

John Banther: I think some people might be listening and wondering, well, wait a second, what about the Four Seasons? What about that? How does that fit into all this? Wasn't that his most famous piece? And actually it was part of a collection of other concertos, wasn't it?

00:31:13

Evan Keely: 1725 was the year they were published. They were published as part of his Opus Eight, which is a collection of 12 concertos. The title of that whole collection is (foreign language) , the Contest of Harmony and Invention. So it's a rather poetic title for this collection of concertos. They were published in Amsterdam, and the first four of those 12 concertos are (foreign language) , the Four Seasons. I think it was the first season of Classical Breakdown, episode three. You and James Jacobs had a wonderful conversation about the Four Seasons, and one of the things you guys point out in that episode is that there are these sonnets that are meant to accompany the music.

It's possible Vivaldi is the author of these poems, one about each season, and it's a wonderful way of exploring this incredibly descriptive music that he composes. And it's not surprising to me these works are so famous because the more you listen to them and think about them so imaginative and thrilling and wonderful and beautiful.

00:32:23

John Banther: They're really quite astounding. I mean, when you really get into it, there's nothing like this. It's almost like... Maybe it's too bold to say, it's almost like a Berlioz Symphony Fantastique moment. It's like, what is this? Where did this come from? And then there's nothing quite like it for a while. So much detail in the music, a lot of detail that's lost on listeners because it's stuff that's just written in the score or clever things. And the sonnets that he wrote, it probably is played too much in all forms everywhere. But I think people often hear just the kind of romanticized version, the maybe slower, sappier... That's maybe a little harsh, but some, it's a little too sappy. When you listen to how it was performed originally in that this baroque practice, in this early 18th century style of music. When you hear it that way, it's extraordinary. It blows me away every single time.

00:33:13

Evan Keely: And I really appreciated your comparison to Berlioz. I think that's an apt analogy to draw. Both cases, Berlioz and Vivaldi are telling a story with music and doing it in a way that nobody before them had thought to do, and just shocking some audiences and thrilling many others. Vivaldi, he's painting these pictures in these concertos, and you hear dogs barking and bugs buzzing and lightning flashing. And who was doing this before Vivaldi? Not a lot of composers. He really had a way of conceiving of music in ways that were fresh and new, and they continue to be exciting to us today.

00:33:57

John Banther: So Vivaldi's lived this life of just great music, composing hundreds of concertos, all kinds of choral and sacred works for Pieta, in that institution. Opera, great success there in the later part of his life. The Four Seasons. I mean, he's just a force to be reckoned with, but like all things, there has to be an end. And this started for Vivaldi in the later part of the 1730s. Now in his late fifties, his music is no longer that fresh, that exciting. He's been there for decades. He's starting to fall off in popularity.

Instead of writing concertos for these performances, he's writing them for private donors, selling off other or older manuscripts for some money. And in 1740, he leaves Pieta, he leaves Venice for Vienna, for reasons we're not a hundred percent sure about. May have been to stage opera, probably likely because of that. I think he wanted to stage opera in Vienna after meeting Charles VI, the emperor at the time, I guess. Unfortunately, they died shortly after Vivaldi's arrival in October of 1740. And then less than a year later, that next July in 1741, Vivaldi himself would die in Vienna, in poverty. And allegedly, Evan, this is hard to believe, no music played at his burial.

00:35:17

Evan Keely: Yeah, it's a sad end to an otherwise stellar career in many ways. Vienna was just really becoming... Beginning to be a great musical center of Europe in the 1740s. And the years prior to that. You mentioned the Emperor Charles VI, the Holy Roman emperor was very enthusiastic about music. Apparently he had met Vivaldi sometime before that, and it hinted that he would be welcome in Vienna. So we maybe Vivaldi went to Vienna for that reason. We're not really sure. But as you said, the emperor died shortly after Vivaldi got there, and the hopes that he had brought to his migration to Vienna never materialized, and he died in poverty and obscurity.

00:36:01

John Banther: One more way I think we can kind of humanize him, I think in a kind of more humor way here, is that when he left in 1740, it sounds like he left rather quickly. He didn't run out of the city at night with his pajamas on or something, but he left pretty quickly. And it's seems to be not because there was some bad situation with Pieta, that's... I've read pushback against that. But what's funny to me is that apparently he just left town and didn't even take care of the lease on the home or place that he was staying. He just got up and left. And I think we've all been there in some way where it's just like, " I just got to get out of here. I don't want to be here anymore." But he just got up and left and didn't take care of the lease on his house.

00:36:40

Evan Keely: Clearly, his affairs were not in order in the final years of his life for reasons that are not entirely clear to us today.

00:36:48

John Banther: And unfortunately, from there, with his death, his music quickly fell into obscurity after 1741. A lot of his music has survived. It was preserved in some way, but many compositions, many concertos, many other things, they're lost. Of course, after 200 years, serious research wouldn't begin on Vivaldi and his music until round World War I and then getting popular in the 1940s. It makes you wonder, Evan, what composer right now is in the middle of their 200 year obscurity?

00:37:19

Evan Keely: Right. We're still discovering music all the time. It may be in an archive somewhere or... There's that, Florence Price's music was discovered in an abandoned house maybe 15 or so years ago. There's manuscripts floating around somewhere. And certainly if they go back to, say, the 18th century, there's still more for us to explore. But even in the music that we have, somebody has to perform it. We want to hear it. And there's so much music by Vivaldi and other composers of this era that we're still just really beginning to rediscover. And I think the more that we can do that, the more we can look into the past as well as encourage living composers and hear their music as well. They're not mutually exclusive and we'll be thrilled by what we can find out.

00:38:09

John Banther: Beautiful. Well, with that comes the end of our story on Vivaldi, and it's time now to read your reviews from Apple Podcasts.

D Bev 79 Left a review, gave us five stars and said, " Love it. This is a fun version of classical light, unpretentious and informative, and a nice way to get access to music composers and musicians, of which I would have never otherwise been aware."

Well, thank you so much, D Bev 79. We all appreciate it. And Evan, do you have anything else for Vivaldi?

00:38:41

Evan Keely: Antoni Vivaldi. You can't turn on the radio on a classical station like WETA Classical and listen for several hours without hearing at least one piece by Vivaldi. He's enormously popular. His music is played all over the world, and some people maybe turn their noses up at Vivaldi and think of him as just writing sort of light frivolous music. And I think we need to challenge that view and to recognize this was a really creative and ingenious composer and a really marvelous and complex human being who left an extraordinary legacy of creativity to the world that we should continue to explore and rediscover.

00:39:22

John Banther: Well said, Evan. I know when I hear Vivaldi next on the radio, I'll definitely take a second, listen and absorb and just remember and think about those times, him walking through Pieta, all those performances and all... Everything he did there, and maybe listen to it from that aspect.

Thanks for listening to Classical Breakdown, your guide to classical music. For more information on this episode, visit the show notes page at classicalbreakdown. org. And if you have any comments or episode ideas, send me an email at classicalbreakdown@WETA.org. If you enjoyed this episode, please leave a five star review in your podcast app and tell a friend. I'm John Banther. Thanks for listening to Classical Breakdown from WETA Classical.