I’ve been fortunate to travel and live in a few places, and I was surprised when I moved to the Washington area by how strong and vibrant the choruses are in the music community. I’ve also performed with several of them as an orchestra musician, and it’s not just the quality of singing but the selection of repertoire as well. That is all to say, we are fortunate to have such a high level of vocal music, and that’s in part thanks to organizations like The Washington Chorus and their Artistic Director Dr. Eugene Rogers.

Dr. Rogers has been with The Washington Chorus since 2020 and he has a list of accolades too long to list here (but they include an Emmy and a Grammy). He wrote about their upcoming concert, Free at Last: A Musical Tribute to Dr. King’s Legacy, the composers, significance, what we can look forward to, and more.

Words from Dr. Eugene Rogers

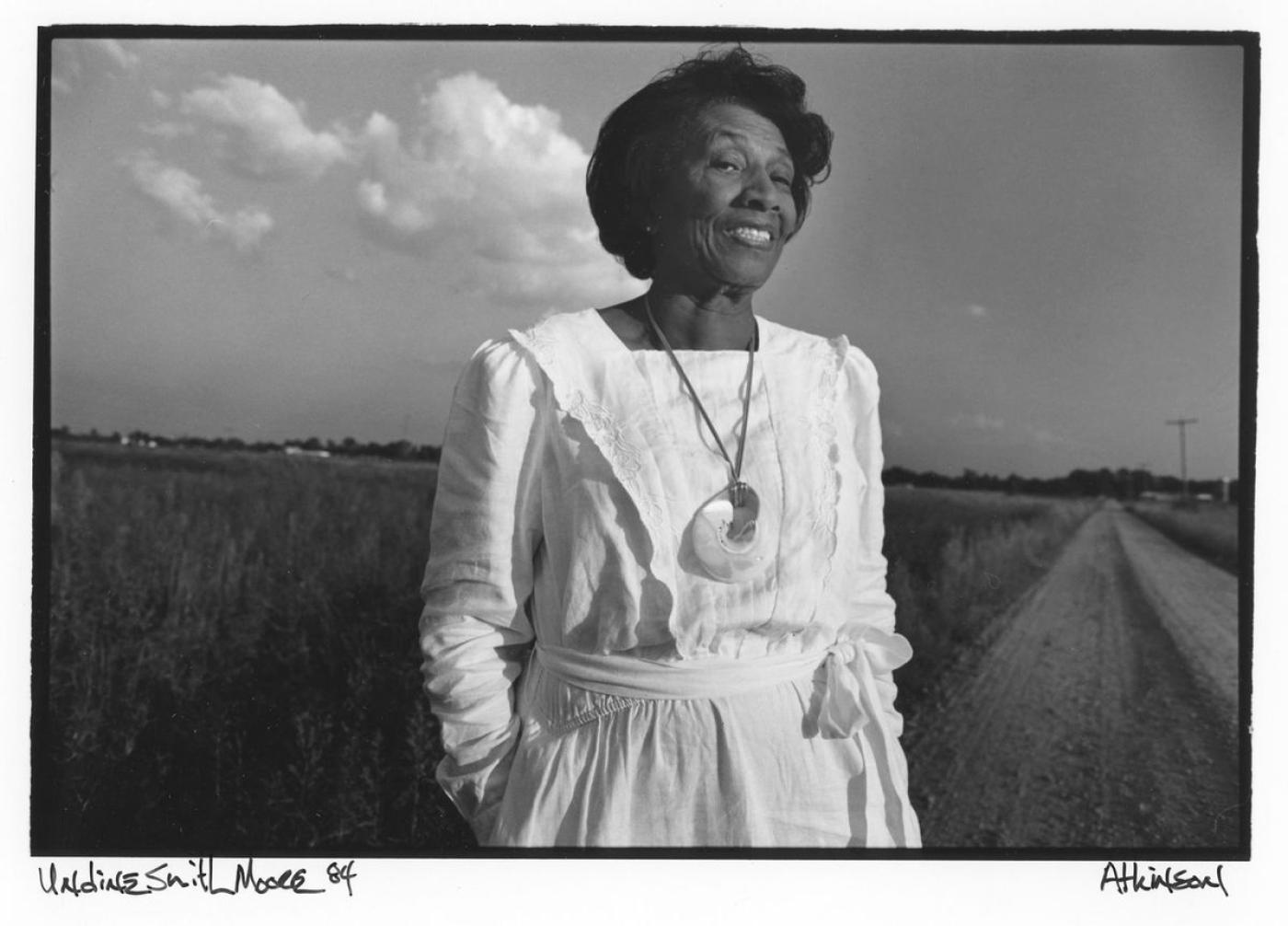

For quite some time, I have been looking for an opportunity to program Undine Smith Moore’s Scenes from the Life of a Martyr. I first learned of the work during my studies as a doctoral student at the University of Michigan and once I discovered Dr. Moore and her seminal work, I knew that I wanted to program it someday. Having been raised in rural Virginia just like her, and knowing exactly what it is like to be an African American within the world of classical music, Dr. Moore’s life and work resonated deeply with my own. In the work itself, I greatly admired the way that Dr. Moore reckoned with the figure of Dr. King: remembering his legacy and acknowledging the grief of his murder, but also not allowing that grief to keep us standing still. I simply needed to bring the work to life.

Knowing that 2023 was the 60th Anniversary of the “I Have a Dream” Speech and the March on Washington, it was finally time for me to bring the work to The Washington Chorus. Having the DC premiere of Scenes from the Life of a Martyr just down the street from where Dr. King gave the speech feels like some small form of justice. It closes a loop for me, and I wish that Dr. Moore herself was alive to see it.

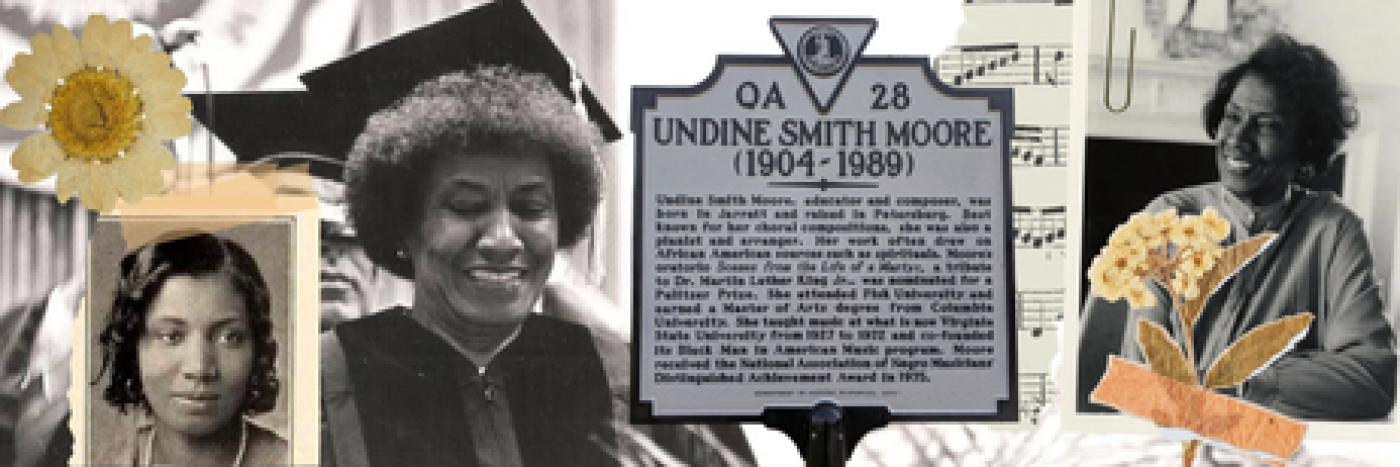

To give a little background (because not nearly enough people know Undine Smith Moore!) Dr. Moore was a prolific composer and steadfast music educator. She has been called the "The Dean of Black Women Composers," and she described herself as “a teacher who composes, rather than a composer who teaches." In her early years, she did not think herself capable of becoming a composer, commenting on one occasion that “one of the most evil effects of racism in my time was the limits it placed upon the aspirations of blacks, so that though I have been ‘making up’ and creating music all my life, in my childhood or even in college I would not have thought of calling myself a composer or aspiring to be one.”

After a childhood full of music in her hometown of Petersburg, VA, not dissimilar from my own, Dr. Moore’s post-secondary education began at Fisk University where she studied piano, organ, and music theory, earning her Bachelor of Arts degree in 1926. From there, she obtained her Master of Arts at Columbia University Teachers College in 1931. Additionally, Dr. Moore studied at the Juilliard, Manhattan, and Eastman Schools of Music, and was notably the first Fisk graduate to receive a scholarship to Juilliard. She joined the faculty at Virginia State College (now Virginia State University) in 1929 and remained there until her retirement in 1972. After her retirement, she continued teaching and lecturing across the country.

Dr. Moore’s compositional style combined elements from the classical tradition as well as her African American spiritual heritage, particularly as she developed that style over the course of her life. She drew upon that same influence in her teaching, championing the inclusion of African American music in the schools and universities through Virginia State’s Black Music Center that she co-founded in 1969. When asked about what made her music uniquely Black, she responded, “I have often been concerned with aspiration, the emotional intensity associated with the life of black people…[and] the capacity and desire for abundant, full expression as one might anticipate or expect from an oppressed people determined to survive.” It is likely for this reason that she wrote so prolifically for voice and chorus, as it allowed her to put that struggle to words as well as to music.

Dr. Moore composed Scenes from the Life of a Martyr, her self-described "most significant work," between 1978 and 1981—earning her a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1982. I should also note that she was the first African American woman to be nominated for that award, an award that an African American woman would not win until 2019—nearly 40 years later. It has only been performed a handful of times, and we are still working with a handwritten score. In fact, we are working with the publishers to create a newly engraved version so that it is more accessible to even more choirs and orchestras.

Much like Seven Last Words of the Unarmed by Joel Thompson that we performed in January, Dr. Moore did not write Scenes from the Life of a Martyr with the original intention to publish it. When interviewed about it in 1989, just a few short months before her death, she said, “I did not write it on commission, or under any pressure, and I worked on it for quite some time before I even thought about publication or performance. I wrote it as a way to make tangible my feelings about Dr. King.'' She did this by intentionally using multiple compositional styles throughout the oratorio to honor a "man of all the people; who had a dream for all men, of all times, everywhere." The piece is in four sections, each covering different periods in Dr. King's life: 1) childhood, 2) young adulthood and marriage to Coretta Scott King, 3) rising notoriety and activism, and 4) his death and legacy. It does not shy away from the overwhelming distress that Dr. King’s death brought about, but it does not conclude in the thick of that anger. Instead, it shifts and builds to a glorious Alleluia, triumphant and radiating with hope. To Dr. Moore, it wasn’t about what had happened, but what Dr. King deserved.

I had long known that I wanted to pair Dr. Moore’s work with a Requiem, not as a funerary work, but to reinforce Dr. King’s own enduring faith and the hopeful tone found throughout Scenes from the Life of a Martyr. Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem quickly became the clear choice.

As most know, Duruflé only published a handful of works (he was notoriously self-critical and fiendishly busy), but this Requiem has become a choral staple several dozen times over since it premiered in 1947. In Duruflé’s own words, his Requiem is "not an ethereal work which sings of detachment from earthly worries," but it is also not the fire-and-brimstone Requiems crafted by many other composers. Perhaps more than all the others, Duruflé's Requiem speaks to an individual’s hopes and fears as they contemplate the fullness of their life and the mystery of the future, making it the true complement to Scenes from the Life of a Martyr. In many ways, the two works are identical in how they do not ignore fear and sorrow, but do not languish in them either.

I want audiences to come away from this concert with a sense of hope, and the Duruflé Requiem carries that thread from the finale of Scenes from the Life of a Martyr—“Tell All My Father's People Don't You Grieve for Me”—all the way through to the final reverberations of “In Paradisum.” Dr. King was a human just like all of us, who grew to mean so much to so many by doing the work as fervently and as righteously as he could, even if he had to leave it unfinished. As Dr. Moore herself said, “All of us can feel a certain kinship with Dr. King, because like him, even humble, ordinary people have dreams and goals that have been unfulfilled. I hope the work emphasizes that the failure to achieve a certain goal does not make lives lack meaning.”

I can only hope that this concert is a worthy tribute to him and the work he left behind for us to do.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.