Eszterháza is a Rococo palace in northwestern Hungary near the Austrian border, built by Nikolaus Esterházy in the 1760s and 70s. Its magnificence has been compared to Versailles and Schönbrunn, and like them, it played a major role in the life of a major composer, in this case Joseph Haydn.

When Nikolaus built Eszterháza, he already had a medieval palace in Eisenstadt, an Austrian regional capital city about fifty miles from Vienna, that the Esterházy family acquired in 1622. This was where Haydn and his orchestra preferred to stay, since that's where their families lived. But Nikolaus increasingly preferred staying in his new palace, a very full day's carriage ride from Eisenstadt or any other urban area, a swampy piece of land in the middle of nowhere, and by the late 1760s it was his official summer residence. It fulfilled Nikolaus's dream to live in an environment where he could enjoy listening to music far from the noise and stress of the city and his business and political concerns. That music was central to the mission and culture of Eszterháza is evident from its design elements, with images of musical instruments everywhere you look. The grounds included a 400-seat opera house, a smaller marionette theater, an ornate music room, and a picture gallery that was also used as a performance space. Every summer these spaces were filled with music, theater and scholarly lectures, many of which were open to the public; people traveled far from the city every summer to listen to beautiful music in opulent settings.

This wasn't an ideal arrangement for Haydn and the musicians of his orchestra, who had no choice but to be subject to Nikolaus's whims; every year he stayed at Eszterháza longer and longer until finally in 1772 Haydn had had enough. He composed the "Farewell" symphony, in which the musicians leave the stage one by one at the end of the work, as a hint to Nikolaus that the musicians needed to get back to their families in Eisenstadt. (He took the hint, and they left the next day.) But aside from inspiring one of Haydn's most famous works, it also inspired an institution that continues to this day: the summer music festival.

The United States, formed just a few years after this incident, turned out to be surprisingly receptive to the Eszterháza model, and every summer many Americans travel far from their homes to beautiful rural settings where they can breathe clean air and spend all day attending performances of classical music. Of course this became easier with the advent of the privately owned automobile (so much for that clean air.) One of the first car-dependent American summer music festivals that is still a thriving concern is Tanglewood, nestled among the Berkshires in western Massachusetts. It began as three concerts by the New York Philharmonic in late August 1934; by 1936 they were replaced by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Serge Koussevitsky. The new festival was considered national news, and in 1937 the NBC radio network broadcast an all-Beethoven concert from Tanglewood (with 8,000 live attendees) across the country. 1938 saw the opening of what is now known as the Koussevitsky Music Shed, which seats over 5.000 people protected from the elements but is open at the back, where thousands more can enjoy the music while picnicking on the grass.

Perhaps inhabited with the spirit of Prince Nikolaus, Koussevitsky quickly expanded his vision for Tanglewood, and by 1940 he established the Berkshire Music Center, described as an “academy for living and working in music”, intended to give conservatory students on track for a professional career an intensive experience of study and performance opportunities. By this time Tanglewood had built two other performance spaces on its grounds, then known simply as “The Theatre” and The Barn.” The faculty included Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith and the principal players of the Boston Symphony, while the students for that inaugural season included Lukas Foss, Alexander Courage (the film and television composer best known for composing the theme music for the original Star Trek series), and Leonard Bernstein.

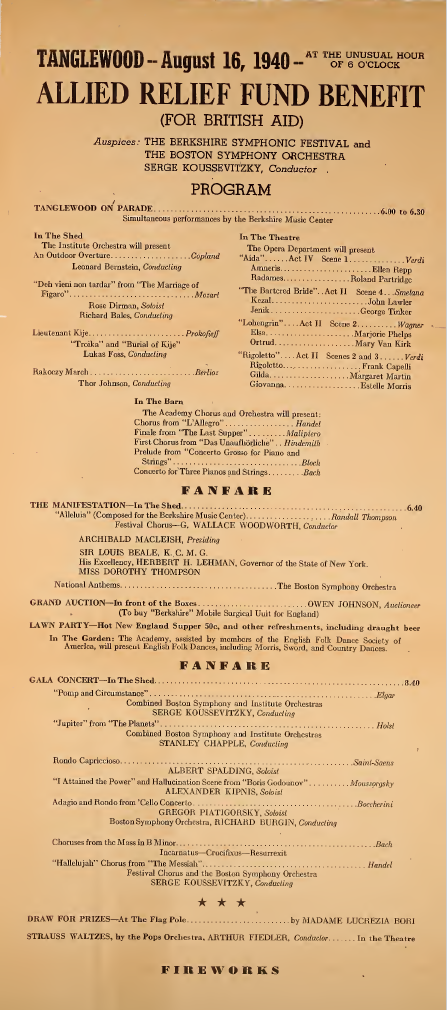

Bernstein, who was 21 that first summer (he would turn 22 a week after the final concert on August 18), was already making a special impression even among such august company. He was given the honor of conducting the first piece, Copland’s An Outdoor Overture, in the Shed in the very first edition of “Tanglewood on Parade”, a special event that was given as a benefit for the Allied Relief Fund. It began with a half hour of simultaneous performances in the three spaces, included a gala concert in the Shed that featured prominent guest performers (violinist Albert Spalding, bass-baritone Alexander Kipnis and cellist Gregor Piatigorsky), choruses from Bach’s Mass in b minor and the Hallelujah Chorus from Handel’s Messiah, and concluded with Arthur Fiedler conducting the Boston Pops in Strauss waltzes to accompany a fireworks display.

In 1948, Bernstein joined the conducting faculty alongside Copland. In 1990, fifty years to the month after his auspicious performance of his mentor’s overture, he conducted what turned out to be his final concert, less than two months before his death.

Because it played such an important role in his life, Tanglewood naturally played an important role in last year’s Bernstein sort-of biopic Maestro. Several scenes were shot there, with no modification required since it largely looks the same as it did 80 years ago! That’s a good illustration of Tanglewood’s timeless quality: the place stays the same, but its tradition has always been to foster creativity and innovation, creating a stable environment for constant change.

This year’s Tanglewood on Parade reflects this balance of the old and new and the direction of the festival as a whole. It’s now an all-day affair, beginning at 2 pm, and features several works by living composers like Caroline Shaw and Valerie Coleman alongside popular favorites like Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, and still ends with fireworks. This year’s edition is a tribute to the late Seiji Ozawa, who conducted the Boston Symphony for 29 years and whose history with Tanglewood rivals Bernstein’s for its longevity; the program will include a new piece by John Williams written for the occasion called For Seiji!

The success of Tanglewood helped inspire the development of other summer music festivals in other idyllic settings throughout the country, including Aspen, Ojai and Interlochen, and there are several other festivals in Tanglewood’s New England neighborhood; focusing on chamber music, there’s the Marlboro festival in Vermont (which also deserves the Hollywood treatment for the role it has played in the development of major classical artists), as well as Yellow Barn and Rockport; or you can enjoy innovative opera productions at Glimmerglass or take a deep dive into an individual composer’s life and work at the Bard Music Festival (this year: Berlioz.)

And there are also a number of festivals that don’t require a major excursion but manage to approximate that Eszterháza-type experience closer to where people live and work, like Chicago’s Ravinia festival and our own Wolf Trap.

Shortly after the establishment of its Music Center, Tanglewood was forced to take a three-year hiatus during WWII, and there was also some curtailment of its schedule due to COVID. But it has proven to be remarkably resilient, and indeed summer festivals in general in the U.S. have thrived even during times when traditional subscription concerts during the rest of the year suffered a decline in attendance. Perhaps Nikolaus was on to something: while music is an essential source of beauty and sanity when we incorporate it into our daily lives (like listening to WETA Classical), we can forge an even deeper connection to it in an immersive environment in which we can actually live on the plane of beauty and order to which music aspires.

I’ll never forget my first visit to Tanglewood, on assignment from WGBH. Being carless, I hiked in from the town of Lenox, allowing time to get there early for a day of interviewing artists and preparing material for that week’s broadcast. As I followed the path and approached the Shed, it seemed like I had the entire place to myself, along with hundreds of enthusiastically chirping birds. But then I turned a corner to face the Shed for the first time, and there was John Williams about to begin rehearsing the Boston Pops for their annual Film Night concert. At that very moment, they launched into the thrilling fanfares leading into the theme from Star Wars. As I was the only person in the Shed, surrounded by 5,000 empty seats, it seemed like they were playing the Star Wars theme just for me.

And that illustrates another unique aspect of the summer festival experience: the possibility of a serendipitous miracle, stumbling upon the beauty and grandeur one needed at that particular moment. When an environment is created for the express purpose of providing beauty and grandeur around every corner, such moments may be unplanned but are hardly accidental. Life is too short not to at least give yourself a taste of what it can be like to live among constant miracles.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.