English is not the only language with some puzzling inconsistencies. Italian has several diminutive suffixes, and not only is there not a clear pattern as to how they’re used, but there are some variants of those suffixes that are unique to certain words, and those studying the language have no choice but to learn those words and their quirks. So, for example, asino is donkey and asinello is little donkey, and albero means tree and alberello means small tree. All well and good; but, speaking of trees, ramo means branch while ramoscello means small branch, and orto means vegetable garden while orticello means small vegetable garden. And, to thicken the plot, sometimes these suffixes also create a word with a different (but related) meaning: mulino means mill, while mulinello means whirlpool.

Things can get even more complicated when diminutive suffixes start interacting with augmentative suffixes. The Italian word for the green citrus fruit we call a lime is spelled (but not pronounced) the same in Italian, which with its article is il lime (eel LEE-ma.) The Italian word for lemon is limone (pronounced lee-MO-nay) which literally means “large lime” (lime + the augmentative suffix -one). The word for “small lemon” is limoncello, which is also the name of a liqueur made from small lemons (and would be a delightful thing to drink in the weather we’re currently having, but I digress.) Which means that the word for small lemon is literally “small big lime.”

Which brings us to how the cello got its name. Through a similar linguistic process, the word violone, or “big viol,” denoting the predecessor to the modern double bass, acquired its own diminutive suffix to describe a smaller version, giving us the word violoncello or “small big viol.” (The final step toward the name most familiar to us happened when violoncello was frequently shortened to ‘cello and eventually lost the apostrophe.)

You may think this is weird, and you would be right to think that. It’s both more accurate and less confusing to consider the cello to be a large violin rather than a small bass, and it’s not a viol. But the nomenclature of string instruments became very messy by the late 17th century. Since the design of the lowest member of the viol family was a constant work in progress throughout the 17th and 18th centuries (and even the modern double bass isn’t completely standardized*), the word violone was used as both as the name of a specific instrument - the contrabasso viola da gamba, with six strings and frets - and as a generic term referring to any bass bowed string instrument, including the now-defunct bass violin**, the true predecessor to the cello.

*(If you look at the members of the double bass section of any orchestra, some of them will be playing four-string basses, some will have a “c extension” on the e string so it can go a few notes lower, while others will actually have five strings; some will use a German bow that resembles a viola da gamba bow and is played underhand, while others use a French bow which resembles a large cello bow and is played overhand; some of the basses will have sloped shoulders and a flat back like a viol while others will have round shoulders and a curved back like a violin; some of the players will be standing up while others will be sitting on stools. No other instrument of the orchestra has this much variance among its ranks, both in terms of the design and the playing technique.)

**(The bass violin is not the same instrument as the double bass. The double bass is also referred to as a contrabass, acoustic bass, and stand-up bass; anyone using the term “bass violin” to identify it is in error.)

The bass violin first emerged in the sixteenth century, where it was the bass instrument of violin bands, which got their start accompanying dancers and outdoor theatre productions, and then started accompanying singers; by the beginning of the 17th century the violin band was the foundation of the instrumental ensemble used to accompany operas, which is how they eventually dominated the symphony orchestra.

In these bands the dominant instrument was what we would recognize as a standard violin, and in addition to the bass violin these ensembles could also include the alto violin (which became known as the viola) and the short-lived tenor violin which pretty much disappeared by the mid-17th century (though it has had its periodic champions; also known as the “octave violin,” it’s currently gaining interest among players of jazz and bluegrass.) This is definitely an instance where size mattered. The celebrated 24 violons du roy was the orchestra of the Versailles court, founded in 1626, and it included 6 violins, 6 bass violins, and twelve violas divided into three sections of four players each; each of those sections played a different size of viola even though they all had the same tuning. The different sizes of viola created different volumes and tone colors that lent a unique richness to the ensemble’s sound. This is an important concept to remember as we trace the development of the cello.

The bass violin (sometimes referred to as Basso de braccio, or in early Italian spelling de brazzo) was considerably larger and louder than the bass viola da gamba which had a similar range, and unlike the viol it was designed like a violin, so it had four strings instead of six, rounded instead of sloped shoulders, f-holes instead of c-holes, a curved rather than a flat back, a bow played overhand, and no frets. It was played either sitting down, where it was large enough that sometimes it sat directly on the floor (supported by a small wooden protuberance from the tailpiece), or standing up with the instrument sitting on a low stool. While the instrument lacked the viol’s expressive qualities, it had a more powerful sound that proved more adaptable than the viol to different performance situations and provided valuable support to the ensemble. While the viol mainly stuck to its own kind in consorts and special appearances that highlighted its unique tone color, the bass violin became a workhorse as the sustaining instrument of the great invention of the 17th century, the continuo section.

Continuo is the foundation of Baroque music. It has been frequently compared to the rhythm section in jazz, in that it is the engine that drives the pulse and harmonic progression of the music. Generally it involved a keyboard instrument (harpsichord or organ, sometimes both), frequently in conjunction with a plucked string instrument (usually a type of lute or harp; guitar was also sometimes used) improvising a textural and harmonic framework for the solo voices or instruments. All the composer would actually notate was the bass line, occasionally supplemented with figures (numbers printed below the notes indicating the intervals above the written note the continuo players should use in their improvising) if the harmonic progression is unclear or unexpected. Scholars have been divided over whether it should be assumed that a bass melodic instrument such as viol, bass violin or bassoon would have played the sustained bass notes; the current thinking is that, at least in music of the 17th century, they should only do so only when the composer specifically asks for it.

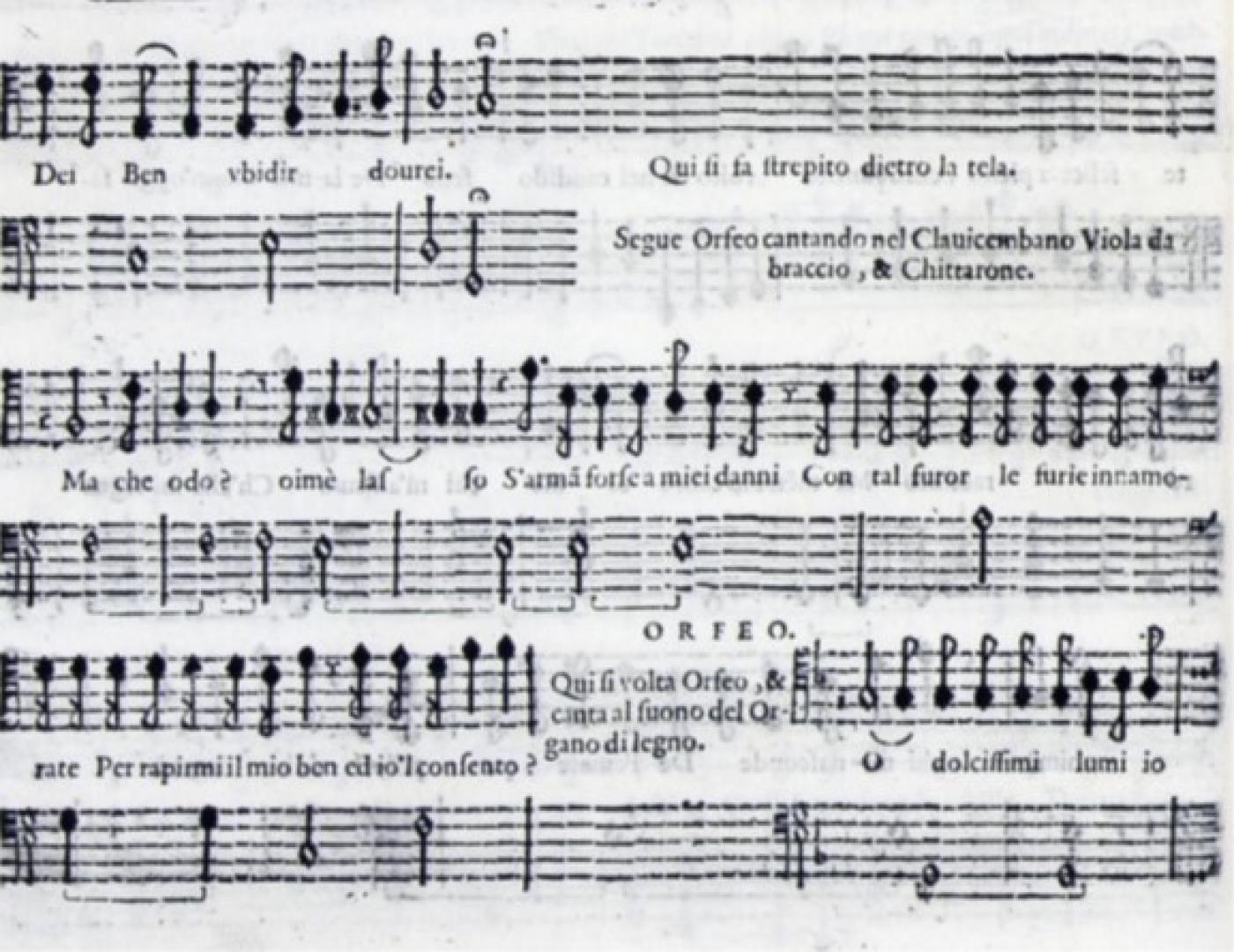

This excerpt from the fourth act of Claudio Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo shows the moment when Orpheus, who had been joyfully marching through Hades up to the earth confident that his beloved Euridice was following him, heard a strange noise and began his fateful spiral into doubt that led to his turning around in reckless defiance of the gods. The rubrics state that the instruments needed for that moment were “Clauicembano” (harpsichord), “Viola da braccio” (meaning bass violin, since that’s the only member of the viola da braccio family that could play the notes that are written), and Chittarone (a large lute commonly used by Monteverdi to accompany singers). Since the only notes of the accompaniment given are those of the bass line, we can assume that that the bass violin played the sustained written notes along with the left hand of the harpsichord while the right hand and the lute improvised an accompaniment that conforms to the implied harmony while providing the emotional atmosphere appropriate to this moment. Monteverdi was the first composer to specifically call for a bowed string instrument to be part of a continuo section, an effect he only used in certain dramatic moments; by the 18th century, the cello, the heir to the bass violin, was used as a full-time continuo instrument.

Earlier in the opera, in the third act, is an even more significant watershed moment for the bass violin: the first time it’s specifically called for by name in a score instead of implied. Here it’s referred to as “Basso da brazzo” at the beginning of the third line of the score (brazzo being an alternative spelling for “braccio”.) The violin parts are notated in soprano clef, which is why the notes appear to be a third higher than they would be in treble clef (the first note of the first violin part is F#.) There is actually only one vocal line; the lower line is meant to be an elaborately ornamented alternative version of the upper line. At the beginning of this section Monteverdi indicated that the continuo line, seen at the bottom, would have been played by “organo di legno” (a chamber organ with wooden pipes) and chittarone, without any melodic sustaining instrument.

The bass viola da braccio (aka bass violin, basso da brazzo etc.) went on to find employment in the numerous opera houses that started to spring up all over Europe, and as I mentioned earlier, it was kept busy in the royal court of France as well.

Sometime around the 1660s, bass violin players started to get some ideas. Now that it was possible to make a living playing the instrument, they wanted to play more melodic material and even start amassing a solo repertoire. However, the instrument was designed to deliver a big bass sound to serve as the foundation for ensemble playing, and its size made it difficult to play virtuosic music in upper registers, so the idea was to make the instrument smaller while retaining the same tuning. They were willing to sacrifice some of its deep resonance for greater agility and versatility. As I mentioned earlier, by this time the term violone was commonly used to refer to the bass violin, so the new smaller, lighter, more agile violone would be called the violoncello.

However, the concept of the violoncello preceded the execution of it. The term first appeared in the 1660s; the first music specifically written for the violoncello appeared in the 1680s; and the major luthiers didn’t start making true violoncellos with their more compact dimensions until the 1700s. Several of Stradivari’s most celebrated “cellos” are actually bass violins that were severely altered and reduced in size in the 19th century. About halfway through his career Stradivarius helped design the new smaller cello, but even those were large by today’s standards, and most of them, too, were forced under the ruthless knives of 19th-century luthiers.

Click here to view the Batta-Piatigorsky Stradivarius Violoncello.

Before we go any further it should be mentioned that there was a faction of string instrument players and builders who fervently believed that all members of the violin family should indeed be played da braccio, supported by the left arm instead of propped up by the legs. Thus there were many champions of an instrument that came to be known as the violoncello da spalla. Spalla means shoulder; the instrument is too large to be held under the chin, but truth be told the shoulder doesn’t have much to do with playing the instrument either. It’s held with the aid of a strap that goes around the player’s neck and is looped around the top and bottom of the instrument in a way reminiscent of the hurdy-gurdy. It has five strings, giving it the combined ranges of the violoncello and the now-defunct tenor violin. The loss of bass resonance is palpable, but the gain of fluency is undeniable. Some scholars think it might the answer to the riddles posed by Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cello Suite no. 6, which is written for a five-string cello, and several cantata movements that call for a “violoncello piccolo”. All that we know for certain is that luthiers kept experimenting with new instruments, and composers kept writing pieces for those experiments.

In any case, with the Bach Suites we come to the true arrival of the cello. There were more changes to come, of course: the baroque bow morphed into the Tourte bow, with a corresponding change in articulation that was discussed in The Story of the Bow; metals were introduced to supplement and even replace the sheep gut used for the strings; responsibility for holding the cello up eventually transferred from the player’s shins to a long sharp metal endpin. With that last innovation the cello went full circle to the oldest surviving string instrument of any kind, the rebab, which was also held upright, played with a bow on strings tuned in intervals of a fifth, and held in place by a spike reaching to the ground.

The Bach Suites have a somewhat rebab-like quality that isn’t shared by his solo works for violin. Since the cello isn’t capable of playing actual counterpoint like the violin can but must instead imply it, Bach wields the essential loneliness of the cello’s sound as a superpower. Throughout the suites the cello has a long conversation with itself that covers the gamut of music and human experience but never lets you forget that you’re listening to one person playing four strings; it’s about the infinite possibilities of the individual. When Bach does occasionally dare to let the cello sound lonely, as it does in the Fifth suite, we can feel the void it’s crying into, and recognize it as the same one we face.

All composers used the cello as a way of projecting their own personalities and brought something new out of it. Bach’s son Carl Philip Emanuel wrote three wonderful cello concertos that are in no way inferior to the two excellent concertos by Joseph Haydn, and all five seem to be craning forward to the Romantic era from the perspective of the Rococo. Boccherini’s concertos and sonatas for the instrument are endlessly imaginative, impossibly virtuosic and constantly entertaining, much how I imagine the composer himself to have been. Beethoven turns the cello into a heroic figure; he was the first to write works for cello and piano as two equal partners, and while he never wrote a solo cello concerto he let it be the dominant soloist in the Triple Concerto, the voice of sanity in many of his chamber works, and he also wrote a concerto-like passage in the ballet The Creatures of Prometheus that deserves to be better known. Schumann wrote both his Five Pieces in Folk Style and his cello concerto late in his life and you can hear in those works both his unique sense of beauty and structure and a heartbreaking representation of his dissociation and mental anguish. And so it goes through Chopin, Saint-Saens, Brahms, Dvorak, Bloch, Elgar, Kodaly, Rachmaninoff, Strauss, Shostakovich, Bernstein – all of whom found something singular to say through the cello that revealed something essential about the composer that couldn’t be said on any other instrument. (Particularly surprising about Chopin, who in his late Cello Sonata finally had something to say that couldn’t be said at the piano.)

Whether or not it’s true that, as has been often said, the cello’s sound is the closest of any instrument to the human voice, it’s certainly true that it’s the instrument that has inspired the most humanity.

Love the cello? Learn more its repertoire and artists from Classical Breakdown!

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.