For more content like this, subscribe to our newsletter to have them delivered directly to your inbox!

On April 13, 1737, George Frideric Handel had a stroke.

On April 13, 1742, Handel led the world premiere of his oratorio Messiah in Dublin.

On the morning of April 13, 1759, Handel, lying on what he assumed would be his deathbed, said his final farewell to his close friends, and when they left he told his servants not to let in any more visitors as he was now "done with the world." It was his hope that he would die later that day, since it was Good Friday. (As it happened, though, he didn't die until the next day, April 14, So much for symmetry.)

So let's go back to that earlier period of exactly five years. In April 1737, Handel was 52, and the evidence suggests that he was suffering from extreme stress, exhaustion and burnout. He was still busy composing, producing and leading performances of his operas; even though attendance and support for them was starting to decline and the politics surrounding rival companies and imperious divas was accelerating their demise, he was trying to salvage them as a commercial enterprise through sheer quantity. He composed three new operas within about two months and frantically prepared them for performance, and while they contain some fine music they have a churned-out quality, betraying the fact that Handel had settled into a too-comfortable formula. He had already begun looking ahead to the transition to oratorios as his major vehicles of expression, and at the same time he was also forced to look backwards as he revived several of his older works for performance. He was living in the past, future and a very stressful present at the same time, and it was taking its toll; in March of that year his friend Ann Granville wrote in a letter that Handel seemed moody and defeated and talked of giving up music altogether. His body responded with what the London press described variously as “rheumatism”, “a Paraletick disorder”, and “the Palsy.”

It took him several months to recover, but he did, and he seemed to regain a sense of purpose and clarity as to how to proceed. His subsequent output was not only remarkable for a recovering stroke victim but, as a significant body of work produced in the space of four years, has few parallels in the history of music.

In December he emerged from his convalescence to write the incredibly moving funeral music for Queen Caroline. He then resumed writing operas, including his final masterpiece in the form, Serse, but they met with little success in the 1738 season, thus spurring his pivot to oratorio for 1739. This resulted in the powerful Old Testament dramas Saul and Israel in Egypt and a delightful setting of John Dryden’s Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day, followed in early 1740 by the colorful Milton homage L’Allegro, Il Penseroso ed Il Moderato. He also returned to instrumental music with a vengeance, producing in the fall of 1739 the twelve concerti grossi he would publish as his Opus 6, considered by many scholars and critics to be second only to Bach’s Brandenburg Concerti among the greatest sets of Baroque orchestral works. And on top of all that he also produced a few organ concertos that he played himself with great flair between the acts of his oratorios - not bad for someone whose right hand had been completely paralyzed just a couple of years earlier.

But then things seemed to slow down and regress as he navigated the ever-fickle terrain of London’s music scene. After an invigorating summer on the continent in 1740, he returned once more to the breach of Italian opera, with disastrous results. His final two operas, Imeneo and Deidamia, written that fall, were considered by contemporary critics to be his weakest major works, an opinion largely shared by today’s critics, and they also established that opera in London was officially dead.

Handel turned 56 in February 1741, a few weeks after the desultory final performances of Deidamia. He had come to London thirty years earlier, and he had conquered it - but now what? He wasn’t hurting for money, and even if he never wrote another note his legacy as one of the greatest composers of his era was already secure. But his recent operatic debacle confirmed the perception that his career was over and London had no more use for him. But he wasn’t ready to retire; he hadn’t come back from near death just for a couple of good years and a couple of disappointing ones. He needed new terrain to conquer.

He found that terrain thanks to two men: the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who invited Handel for an extended residency in Dublin; and Charles Jennens, his collaborator on Saul and L’Allegro, who gave him a radical new libretto consisting entirely of Bible verses that managed to condense the spiritual essence of the entire New Testament into a work taking less than two and a half hours to perform.

It has been pointed out that to the extent that the work can be said to have a narrative, it covers the largest time span of any oratorio or dramatic work, beginning with prophecies from the Old Testament and ending with the ending of time itself. It inspired Handel's imagination and creativity, and he immediately went to work in the summer of 1741, completing the original manuscript in 24 days. While he liked the libretto, however, it's evident that Handel's conception of what it was about differed greatly from its author's. Jennens expected that Handel would deploy the kind of heightened drama and rich orchestration that he used in their two previous collaborations. But Handel saw something in the libretto that its own author (or really a compiler, since the words are all taken directly from scripture) did not see: an oratorio for the people. Handel deliberately composed it so that it could be performed in a variety of ways by both amateurs and professionals, suitable for both small theaters and large cathedrals, in a direct musical language that facilitated the message of the words. Handel could be said to be anticipating 20th century works that blur the line between liturgical and theatrical, sacred and secular, like the gospel tunes that have climbed the pop charts or Broadway musicals about Biblical figures. While Handel made a couple of changes to the score at Jennens’ insistence, they never really did reconcile their basic conceptions about the piece,

Jennens was also upset that Handel decided to premiere the work in Dublin. But doing so would test Handel's proof of concept: he had no idea what to expect in Dublin in terms of their musical resources, He even shipped his own organ to Dublin, and arranged for some of his favorite vocal soloists from London to join him there. He assumed correctly that there would be some sort of choir and string section he could work with, and that he could find two trumpeters and a pair of timpani to play the four sections of the score that employ them. This way those three musicians wouldn't have to come to any rehearsals: they could just come in earlier on the day of performance to rehearse the three choruses in which they participate: "Glory to God", "Hallelujah" and the final chorus "Worthy is the Lamb". Also, one of the trumpeters is needed for the aria "The Trumpet Shall Sound." The rest of the piece is just strings and singers, with the composer conducting from his organ. This economy of means stands in stark contrast to Saul, which also required woodwinds, trombones, a harp and a carillon! But, as Handel demonstrated in his Opus 6 concertos, limiting one's palette to strings need not limit one's expressive possibilities.

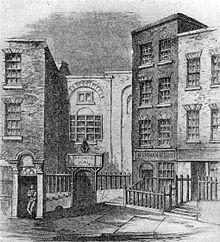

Handel set out for Dublin on November 4, 1741, arriving there two weeks later. He found a warm and enthusiastic reception, a far cry from the studied jadedness of the London audience. The trip succeeded in rejuvenating him and reviving his spirit. He began performing concerts in December at a venue, the Great Music Hall on Fishamble Street, built specifically to present benefit concerts for the release of imprisoned debtors.

At this point, it's easy to imagine that Handel had an epiphany: this is why he had the impulse to keep Messiah's performance requirements modest and flexible - so it could be easily adapted for use in benefit concerts. In this way, the work would not only be about Christianity, but be Christianity in action. (It's telling that the ostentatious Jennens, who wore his supposed devoutness on his sleeve and considered himself a theologian, never understood this aspect of Handel's interpretation of his work, and kept pushing the composer to make the music more elaborate.)

And so it happened that on April 13, 1742, Messiah was performed for the first time to a packed house of 700 people on Fishamble Steet, so crowded that the men were asked not to wear their swords and the women asked not to wear hoops in their dresses. The performance raised about 400 pounds (a little over $60,000 in today's money), which secured the release of 142 prisoners and also provided substantial contributions to two local hospitals.

Messiah's premiere in London the following year was clouded by the controversy over performing a sacred work in a secular space, a public theater. Its name couldn't be used in advertising or on the program, so it was presented as "A New Sacred Oratorio." It received three performances that year, and two more in 1745; the work did not generate enthusiasm at first. Its proper title was restored for a performance in 1749, and the following year Handel started the tradition of giving annual performances of the work to benefit Foundling Hospital, which continued for the rest of Handel's life. Starting in 1755 he had to have one of his pupils direct the performance due to his failing eyesight.

Handel was in the audience for the benefit performance on April 6, 1759, which turned out to be the last time he left his house. He died eight days later, not seven as he would have preferred. He had good reason to attach significance to April 13, but he had a little too much life in him to stick to the calendar.

Handel's Messiah on NSO Showcase

The National Symphony Orchestra performs Messiah with Fabio Biondi and the Choral Arts Society of Washington.

Sign up for the WETA Classical Newsletter

Did you enjoy this blog? Sign up for our newsletter here and have content like this delivered right to your inbox.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.