"The composer of West Side Story was 72."

I'll never forget hearing those words coming out of a television set as I was quickly passing through a hotel lobby on October 14, 1990. I wasn't shocked; a press release had come out just a few days earlier stating that he was retiring from conducting, and I had heard how much he struggled getting through what turned out to be his final concert at Tanglewood two months earlier. And considering that he was an asthmatic chainsmoker who maintained a punishing schedule all his life we should be grateful that he made it past the Biblical allotment of three score and ten.

Still, the death of Leonard Bernstein felt tragic.

Had he hung on for another decade, he would have witnessed his vindication. By the end of the century, composers had largely re-embraced tonality, the musical establishment had abandoned its litmus tests for what constituted Serious Music, stylistic eclecticism was no longer an insult as genre lines began to blur, it became increasingly acceptable for artists to voice their opinions on politics and social issues, and a new generation of conductors steeped in historical performance practice started using gestures and affects of intense physicality and expression; in other words, everything Bernstein was criticized for being during his lifetime was suddenly okay to be. And the culture understood this: his musicals were revived on Broadway, orchestras were performing and making new recordings of his concert works, and teachers started showing videotapes of his Young People's Concerts to their kids. His MASS was performed at the Vatican. And his hundreds of recordings continued to sell well as they were re-released in new formats.

Gustav Mahler said "my time will come." He was right, and Bernstein, who identified so deeply with Mahler, could have accurately said the same thing. It's too bad neither man lived to see his time arrive.

However, there might have been a downside. Bernstein might have spent that decade trying to compose his masterpiece and realizing he didn't have one, at least not in a form he would recognize as such. And that's why those words out of that television set were so lacerating; he spent the second half of his life trying not to have West Side Story be in the lead sentence of his obituary. (Perhaps he forgot that when Igor Stravinsky died in 1971, every single obituary led with either The Firebird or Le Sacre du Printemps, which were nearly sixty years old by that point, whereas WSS was only 33 in 1990.) Whether or not one would call MASS or the Norton Lectures his true "masterpieces" is irrelevant, as are the various ways West Side Story shows its age. All we need to know is: Bernstein's life mattered to the art of music and the culture at large, and continues to matter.

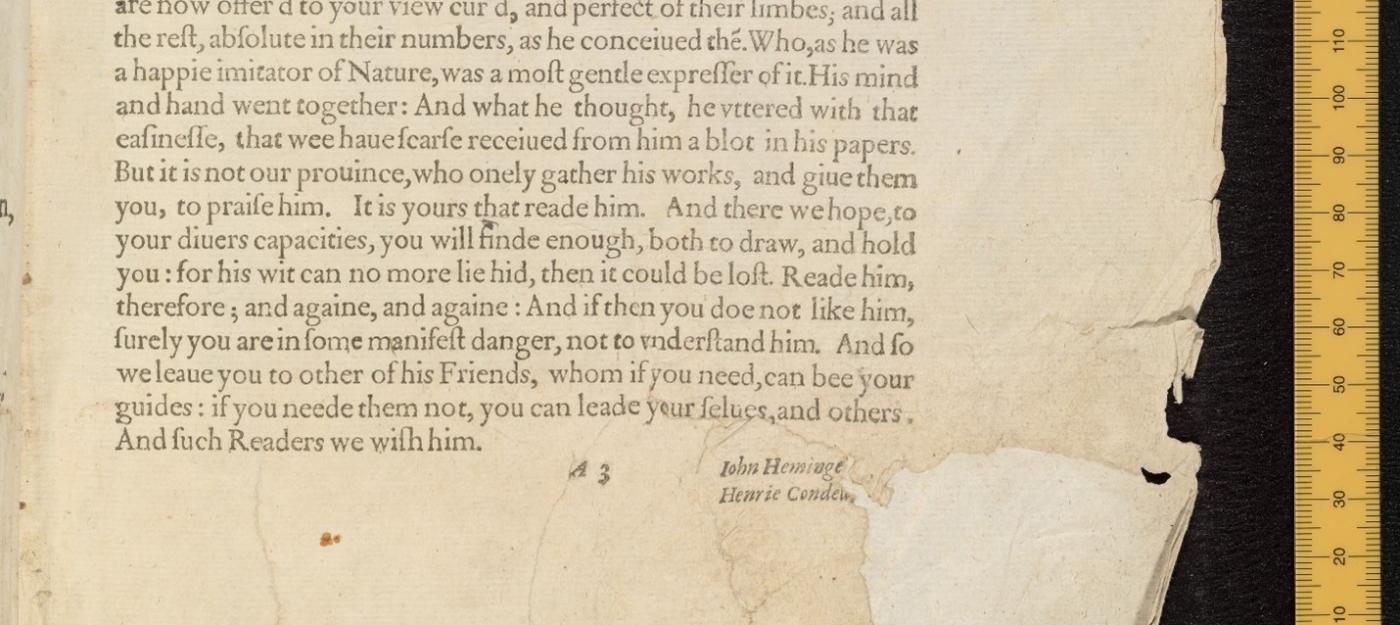

In fact, it's easier to talk about Bernstein in the context of an article supposedly about Shakespeare than it is to talk about one of the great composers usually compared to him (Monteverdi, Beethoven, Verdi, Bob Dylan, etc.) Shakespeare was not a typical producer of groundbreaking masterpieces. He was not, judging by the way his friends and colleagues wrote about him in the dedicatory pages of the First Folio, an eccentric recluse for whom the rules don't apply, who would retreat to his cave and emerge victorious after a hard won battle with a perfect work that's too great for his mediocre contemporaries to understand. No, Shakespeare was a man who put on shows with his friends who all had the common goal of making a living and being liked and respected enough by powerful aristocrats that they could avoid trouble in what was, in the waning years of Elizabeth's reign, virtually a police state. Shakespeare succeeded by creating theater that spoke to everyone and tapped into primal truths about what it means to be human. To quote John Heminges and Henry Condell, his fellow actors in the King's Men who came up with the crazy notion to preserve their friend's work for all time in the First Folio: "...as he was a happie imitator of Nature, was a most gentle expresser of it. His mind and hand went together: And what he thought, he uttered with that easiness, that we have scarce received from him a blot in his papers."

You certainly can't say that about Beethoven.

To be sure, Beethoven is a compelling and inspiring figure and his personal story is heroic. Which is why he's iconic and his music will always speak to us; even those who don't know his biography will hear it in his music. But Shakespeare was a different kind of genius. Our limited knowledge of his life is immaterial to our appreciation of his work.

And, conversely, our massive knowledge of Bernstein's life is ultimately immaterial to his work. When the new film Maestro comes out we will all be steeped in the story of his life, but it won't affect how we listen to his recordings of Brahms symphonies or even his own music. In the case of both Shakespeare and Bernstein, one the creator of masterpieces and the other the conduit for our enjoyment of them, it's all about inviting us to get excited about the same things they're excited about. When you talk about either of these men, you end up talking about everything.

Tonight's featured work is the Symphonic Dances from West Side Story. The work has become so well known that it's easy to forget how intense it is, and how it's atypical of orchestral medleys of Broadway shows. There's no trace of most of the musical's most famous tunes like America or I Feel Pretty. In fact, it's perhaps closest in spirit to the Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev works we heard last week: it has a kinesthetic sensibility – we can feel bodies moving as we hear it – as we make our way through the story, punctuated by violence and soaring melodies.

Come to think of it, perhaps Bernstein's personal story is relevant. There was certainly something star-crossed about his marriage, a hint of Romeo and Juliet, two people who had a feeling that being together wasn't the best idea but did it anyway. And Shakespeare's marriage to Anne Hathaway, eight years his senior whom he married when he was 18, may also have been a version of that story.

My own parents had a Romeo and Juliet-type story, with a sad ending, and I can't imagine the number of Romeos and Juliets there are at this very moment in war zones across the world.

Shakespeare will always be relevant because he writes about all of us.

The Life and Music of Leonard Bernstein

Learn more about Bernstein's West Side Story!

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.