No one would call Romeo and Juliet Shakespeare's greatest play. Its emotional tone is wildly inconsistent; it has much more in common with his comedies and even some histories than it does with any of his other tragedies. Its textual problems are legion; many passages require a lot of detective work, deducing which word from which of its various sources makes the most sense (or is the least improbable) just to produce a coherent speech. Doing that work pays off in revealing some soaring poetry and powerful prose, but the characterizations are crude by Shakespearean standards, requiring extraordinary acting and shrewd casting to make them believable - though even the best efforts will not produce a credible Romeo, a role that is more challenging than Hamlet. The play is full of long expository speeches that stop everything dead in its tracks, that whole business with the sleeping potion is like bad science fiction - I could criticize R&J for days, but it doesn’t matter, because there's something about the passion of it all that overrides its sloppiness. It’s a hot mess, as the kids say, and that adds to its power, because it captures the messiness and the danger of adolescence in a way no other work of art does quite as well. Shakespeare managed to convey how it must feel to meet someone and live out your whole life with them in three days, which is a powerful metaphor for that dangerous and exciting time when you’re suddenly as tall as your parents and you have just enough life skills to function independently but without any wisdom or experience and with a lot of hormones and peer pressure. This is when you’re a danger to yourself and others and every action you take and decision you make has the potential to alter the course of your life.

There is an analogous place in the development of an artist. It's not when they're a teenager but when they've been active for a few years and need to feel that what they do matters and to show that to the world. It could happen as early as one’s 20s or as late as one’s 40s when the need arises to make that big messy statement that breaks all the rules - and in fact Shakespeare wrote this play in his early 30s. Tchaikovsky wrote the first version of his Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture when he was 29 but then revised it throughout his thirties; Leonard Bernstein wrote West Side Story, his version of the play, in his 30s; Prokofiev wrote his ballet Romeo and Juliet in his early 40s. And for that matter Beethoven was 29 when he wrote his first string quartet; he said the slow movement was inspired by the tomb scene in Romeo and Juliet. Each of these works represents a rite of passage in that composers’ development analogous to the position the play holds among Shakespeare’s own works.

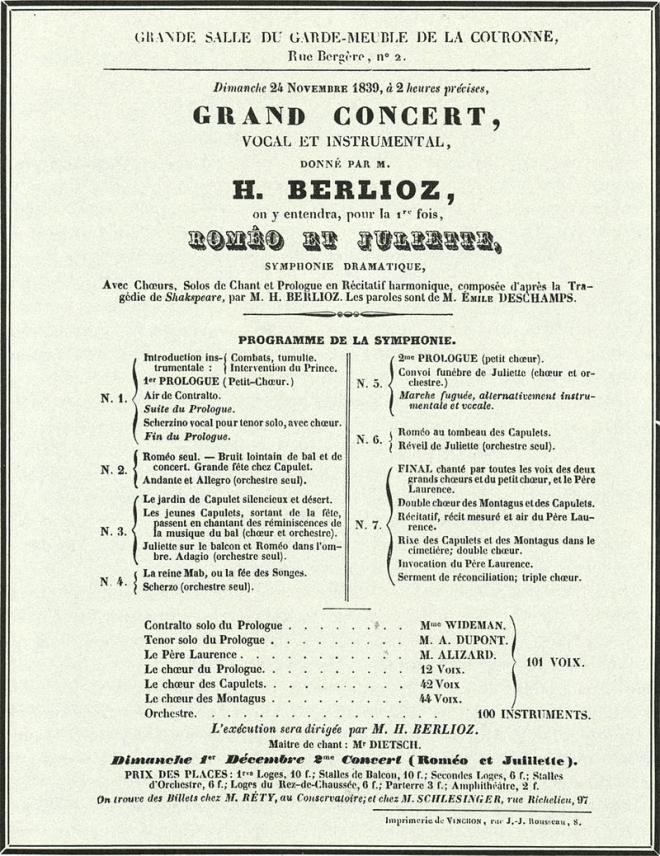

Hector Berlioz began his journey with the play when he was 23, the age at which he saw it staged in Paris starring his future wife Harriet Smithson. In his Memoirs, he described the effect the play had on him: “… to witness the drama of that passion swift as thought, burning as lava, radiantly pure as an angel's glance, imperious, irresistible, the raging vendettas, the desperate kisses, the frantic strife of love and death, was more than I could bear.” He immediately started planning his symphonic treatment of the work, collaborating with his librettist Emile Deschamps to work out its structure just a few months after that performance that left Berlioz shattered.

But then he set it aside; while the R&J project was never far from his thoughts, he realized he needed to work his way up to it, both to develop his skills as a composer and to gain the reputation and resources required to do justice to his vision for the work. (There was also an important negative influence: seeing Bellini’s operatic version of the story, I Capuleti e i Montecchi, served to clarify for Berlioz what he did NOT want his own version to be.) So that initial rush of delirious passion he described so fervently after seeing Romeo and Juliet was actually channeled into Symphonie Fantastique; it would be another decade before he finally decided he was ready for his R&J, made possible by a generous gift from Niccolò Paganini, who upon hearing a performance of Harold in Italy (a work he rejected as a vehicle for his own playing), gave him 20,000 francs and called him the next Beethoven. Berlioz had just turned 35, and he spent the next nine months composing the piece. It received its premiere, a series of three performances that utilized over 200 musicians, around the time of his 36th birthday. It was an immediate success, but he nevertheless made extensive revisions to the work for another eight years before allowing the score to be published.

And what IS this piece? He called it a “Symphonie Dramatique”. At this point, in 1839, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was fifteen years old and was still unsurpassed in pushing the boundaries for what a symphony could be. Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette is as long as Beethoven’s Seventh and Ninth Symphonies combined, and requires voices not just for its finale but also in its extended Prologue. It remains a unique work that defies easy categorization, but its structure that looks so disjointed on paper finds its own thrilling logic in performance - not unlike Shakespeare’s original play.

The symphony is divided into three parts, each containing multiple sections or movements. (Mahler later borrowed this structural concept for his own Fifth Symphony.) The first and third sections depict the action of the opening and closing scenes of the play in a way reminiscent of an oratorio, using voices and Deschamps’ words to convey the narrative of the street brawl of the two warring families and the Prince’s intervention in the beginning, and the funeral for the merely sleeping Juliet, the tragic tomb scene, and the final plea for reconciliation by Friar Lawrence at the end. The second part, depicting Romeo’s loneliness, his crashing of the Capulet’s ball with his friends, meeting Juliet there, abandoning his friends to discover Juliet on her balcony and exchanging vows of love with her, and a Scherzo based on Mercutio’s Queen Mab speech - is almost all instrumental, save for a brief depiction of revelers singing snatches of songs as they leave the ball.

It is the second part that we will be hearing tonight; it’s forty minutes of music, and had Berlioz been slightly less ambitious he could have just presented this as a symphony in itself. The quasi-cinematic specificity of his tone painting makes words unnecessary. We go through the journey of this magical summer night, a moment in time like that one night we all had in our teens when we finally got a taste of the realization of our dreams, while the scherzo reminds us that, just as in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, fairies symbolize the ways in which we are steered by forces beyond our control, whether it’s our hormones, peer pressure from our buddies that leads us into uncharted territory, or the tribal conflicts that pre-ordain our doom, creating walls that not even love’s light wings can o’erperch.

Near the end of his life, Berlioz said that the second movement of this section of the symphony, Scène d'amour, was his favorite among all his works. Wagner cited it as a major influence for his own Tristan und Isolde. But Arturo Toscanini did them both one better, calling it simply “the most beautiful music in the world.”

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.