The First Folio - i.e. Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies Published according to the True Originall Copies - was published 400 years ago, seven years after Shakespeare's death. It was a massive project that took nearly two years just to typeset, let alone the daunting task of identifying authoritative texts for each of the 36 plays it contains and the settling of some complicated rights issues. The earliest mention of the book appeared in 1622, but the date on the cover is 1623, its first recorded sale (two copies to the baronet Sir Edward Dering) took place on December 5, 1623, and the Bodleian Library at Oxford got their copy soon afterward. There are 235 copies of the book known to presently exist, and it's thought that represents about a third of the total copies originally printed. The owner of the largest number of these surviving First Folios - 82 - is the Folger Shakespeare Library, plus the Library of Congress has two of its own, which is just one (or 84) of the reasons why Washington, D.C. is perhaps the most significant center for Shakespeare research outside the UK.

Therefore it makes sense that this milestone should be commemorated in the nation's capital. The Folger is still in the midst of a major renovation project so its esteemed Folio exhibit isn't currently open to the public, but its Elizabethan Theatre is about to reopen after a three-year hiatus, and it will join five other esteemed local performing groups - Shakespeare Theatre Company, Studio Theatre, The Washington Ballet, Washington National Opera and IN Series - for the Shakespeare Everywhere Festival, celebrating the Bard with seven distinctly different takes on his work.

In going through the descriptions of each production, I'm struck by how much music is used to define their different approaches, and that three of them involve classical music. This is to be expected of the WNO, which is mounting Charles Gounod's Romeo et Jueliette at the Kennedy Center in November. The Washington Ballet is presenting "Such Sweet Thunder", a program of shorter works and excerpts that utilized the music of Prokofiev, Mendelssohn, Shakespeare's contemporary John Downland, and Duke Ellington. Most audaciously of all, IN Series presents "The Promised End," which promises "a unique imagining" of King Lear "alongside" Verdi's Requiem, and it sounds like we'll just have to see it to find out what they uniquely imagined - and based on their long history of inventive and spellbinding theatrical explorations, it's sure to be worth the ticket.

It’s actually not surprising that a festival devoted to Shakespeare would assign music such a prominent role. Music was a central element to the theatrical productions of his time. The actors were expected to sing and dance, musicians were occasionally given lines and were sometimes part of the action, and many different types of instruments are specified throughout the plays: violins, recorders and a variety of lutes were used to accompany dances and songs and provide a melancholy affect for the sadder scenes; trumpets for military tattoos; horns in hunting scenes; “hautboys” (i.e. shawms, the early version of the oboe) for both celebratory parades and, when played off-stage, for other-worldly effects like the appearance of ghosts and demons; and an assortment of percussion instruments used for both music and sound effects.

Dancing was an integral part of Elizabethan stage productions, and there are many references to dances of the time in Shakespeare’s plays. There are references to the galliard in Twelfth Night, Much Ado About Nothing, and even Henry V:

The Prince our master

Says that you savor too much of your youth

And bids you be advised there’s naught in France

That can be with a nimble galliard won.

The coranto is referenced in All’s Well that Ends Well and Twelfth Night:

Why dost not thou go to church in a galliard and come home in a coranto? My very walk should be a jig.

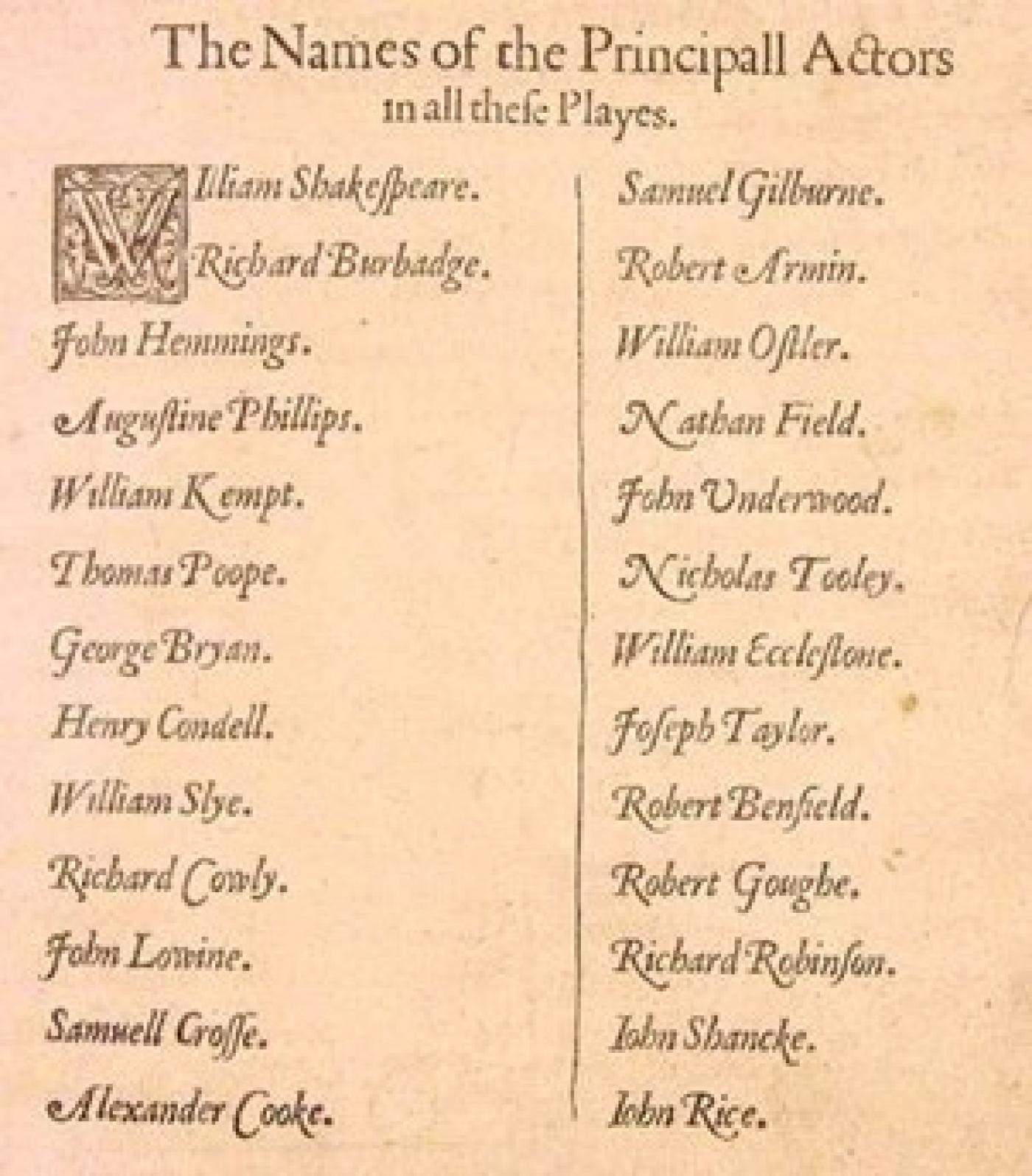

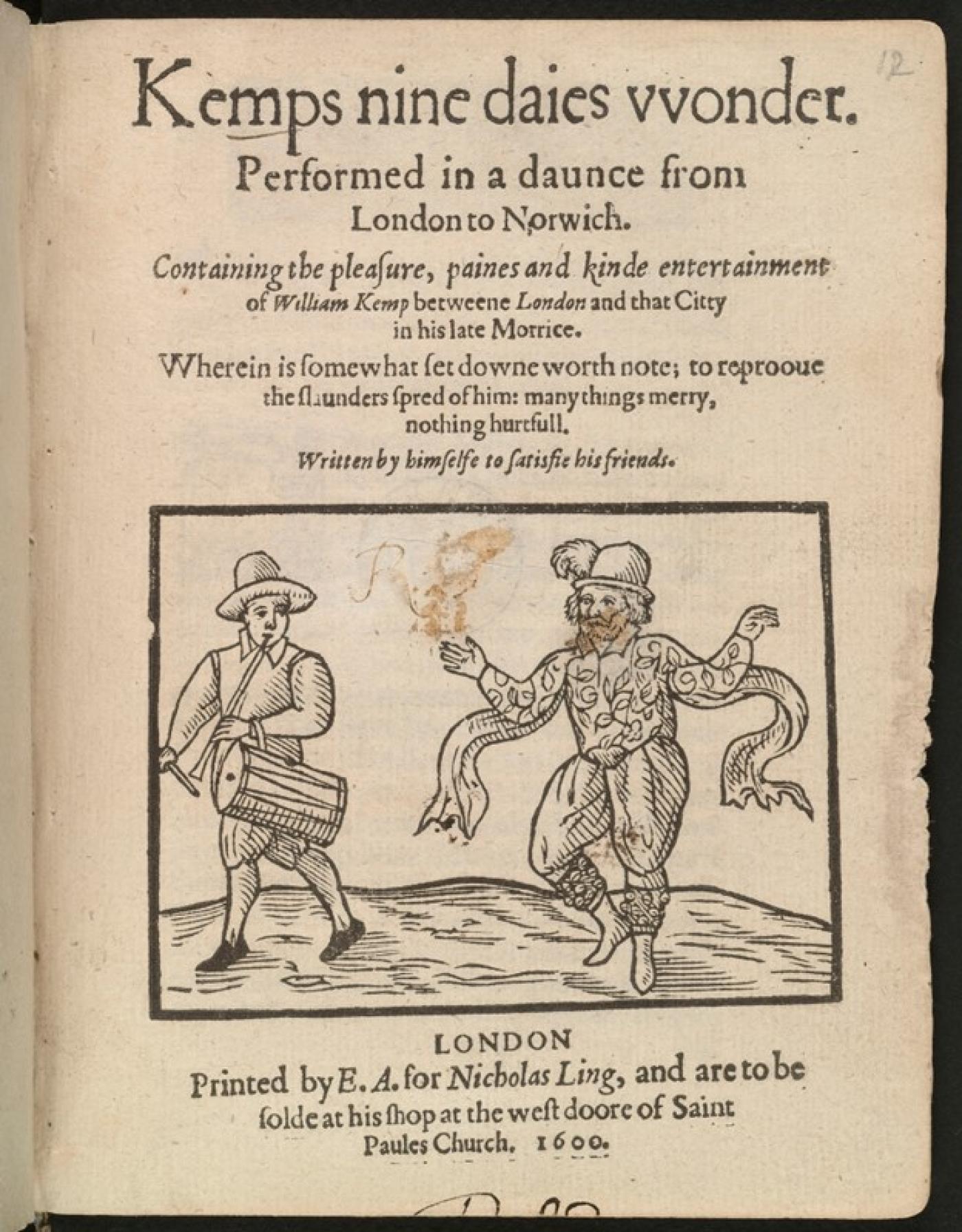

William Kemp (spelled Kempt in this list of actors in Shakespeare’s theatre troupe The King’s Men as it appears in the First Folio) was a noted dancer who played the major comic roles in Shakespeare’s plays. In 1600 he made a name for himself by dancing all the way from London to Norwich (about 120 miles) in the space of nine days. Kemp’s Jig was a morris dance tune that was composed later that year in tribute to his accomplishment.

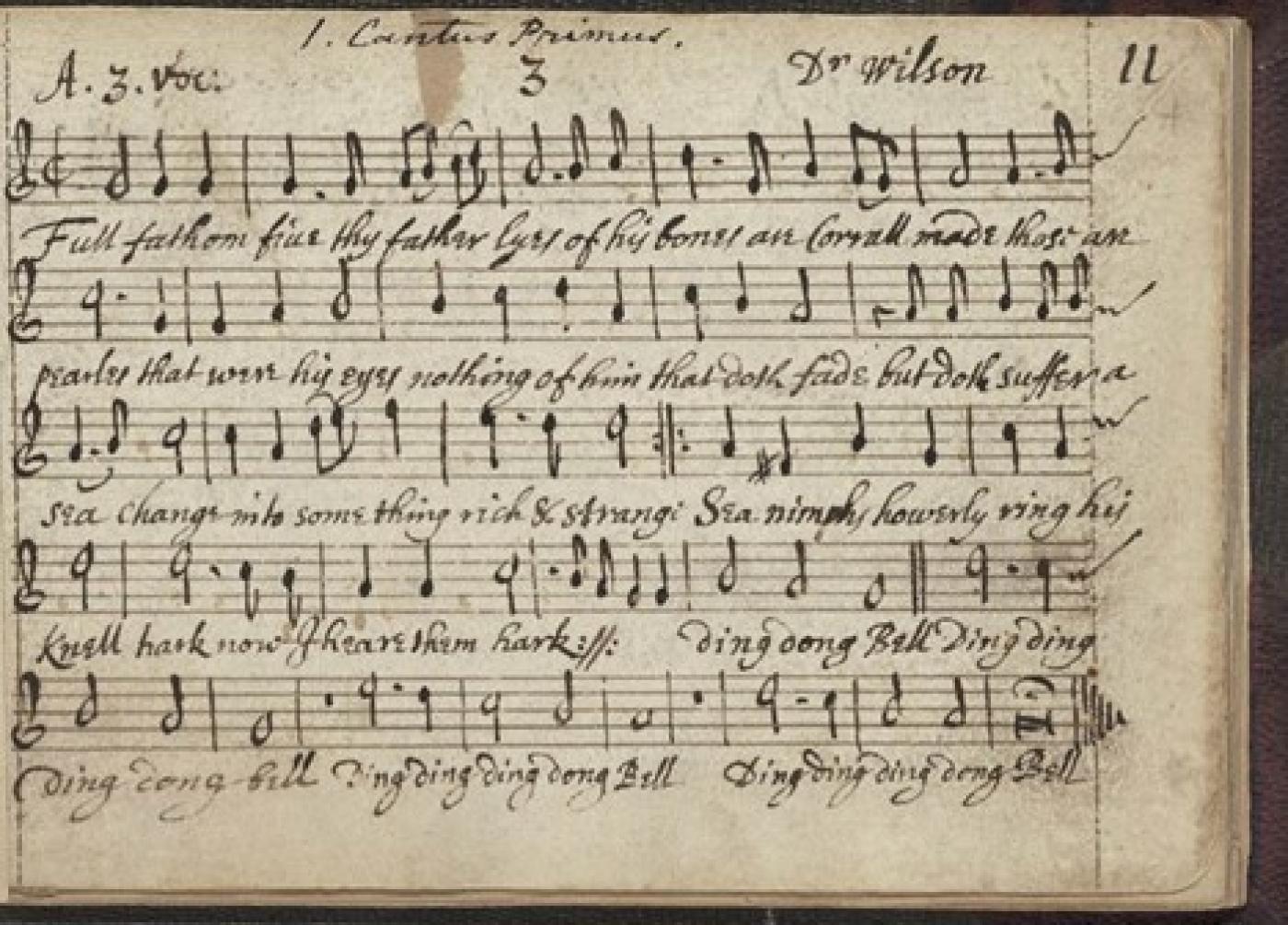

The only composer whose association with Shakespeare can be confirmed is the lutenist Robert Johnson, who wrote the original settings of two songs in The Tempest. It’s also highly likely that he worked with Thomas Morley, the most successful composer of secular music in the Elizabethan era, who lived in the same parish as Shakespeare and to whom is attributed at least one setting of his texts. He was also was doubtless familiar with the work and reputation of Anthony Holborne and John Dowland.

Tonight’s playlist:

Holborne: Noel's Galliard/Coranto: Heigh-Ho Holiday

Kemp's Jig

Dowland: Queen Elizabeth Her Galliard

Playford: Nobody's Jig

Johnson: Full Fathom Five

But Shakespeare’s association with great musicians did not end with his death in 1616. In fact, with his death, his musical journey was just beginning.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.