Editor's Note: Tune into Front Row Washington on December 30 at 9PM ET for a performance of Rhapsody in Blue by Simone Dinnerstein and the United States Air Force Band from the Library of Congress. Read more on this program from the Library of Congress here.

This is what we can agree on: the premiere of Rhapsody in Blue took place 100 years ago on February 12, 1924, and its composer, George Gershwin, was a genius.

Geniuses can be inconvenient. They can be simultaneously avant-garde and reactionary, both in unfashionable ways. It’s not that they can’t “read the room,” so to speak, it’s that deep down they know that their relevance is rooted in their ability to stay one step ahead of the room, unafraid to be rejected or misunderstood by those who can't keep up. If it seems that they are occasionally tone deaf to prevailing trends, conventional wisdom and the burning social issues of their time, it's because on some level they know that their work will last while those seemingly urgent concerns are transitory and will eventually be shown to have little to do with the worth of their creations. And they will double down on this seeming tone-deafness if they sense that their time on this earthly plane is short.

There are several examples of this type of genius in the realm of music - J.S, Bach, Mozart and Beethoven all check off these boxes - and the one that stands out in the United States of the 20th century is George Gershwin. While Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven all generated some degree of controversy during their lifetimes, they have since been securely canonized. The debates over Gershwin's legacy, however, continue to this day. His opera Porgy and Bess generated controversy from its first performance, and its worth has been vigorously debated among both Black and white critics ever since; the response to its revivals on Broadway 2011 and at the Metropolitan Opera in 2019 showed that the arguments about it have continued unbated for over eighty years. The declaration in 1969 by the African American cultural historian Harold Cruse that the opera is "the most incongruous, contradictory cultural symbol ever created in the Western World" still resonates today, and, judging from the strong feelings it still engenders on the occasion of its centenary, it applies to Rhapsody in Blue as well. But let's stick with Porgy for a minute.

It's worth considering what its controversy is about. After all, what Gershwin did in that work was not so different from what Georges Bizet did in composing Carmen. In each case the composer based the opera on a well-researched novel that told a tragic story about a place hundreds to the miles to the south of where it was written (900 miles from Paris to Seville; 750 miles from New York to Charleston); both composers devised a unique musical vocabulary for their respective works steeped in the folk traditions of their settings; the first productions of both operas were financial flops, and both composers died in their 30s soon after these premieres thinking that the opera they considered their greatest work was a failure.

The difference was that in 1875 no one questioned the right of a Frenchman to tell a story about Spanish and Romani people. And there is no indication that Bizet ever traveled to Spain, whereas Gershwin spent a summer in South Carolina specifically to do research for his opera. But one could argue that doing so literally made him a tourist among people capable of telling their own stories - and nineteenth century France was not reeling with the recent history of slavery and present condition of oppression of the people Bizet was writing about.

Gershwin lived during the beginning of a transitional period that in many ways we still inhabit. It's easy to say that music is a universal language when you're the one making money off the idioms you borrowed from a culture that is still suffering from centuries of being exploited in every way possible. But is Gershwin, the son of Jewish immigrants who fled the pogroms in Ukraine and Lithuania and moved to the United States just a few years before his birth in New York in 1898, and whose father worked in a shoe factory, responsible for that history of exploitation? Did he have the right to follow the dictum that "good artists borrow, great artists steal"? Does anyone really have that right?

In any case, Gershwin, like countless other musicians before and since, claimed that right, and, inconveniently, turned out to be one of the handful of musical geniuses whose undisputed greatness ensures that his work and reputation survives despite the slings and arrows of its critics. After all, Gershwin did just what Antonín Dvořák advised American composers to do, and what he himself did in his New World Symphony: use the African American musical vocabulary as the basis for the composition of symphonic music. And just as Dvořák fought to have Black students admitted to the National Conservatory, Gershwin fought for the equal treatment of the Black performers he worked with, used his influence to desegregate several performance venues, and insisted that Porgy and Bess always be performed by an all-Black cast. (On the other hand, his first big hit was "Swanee," which became successful when Al Jolson performed it in blackface - another great immigrant artist claiming questionable rights.)

The debate rages on. Just a couple of weeks ago, an article in The New York Times declared Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue to be "The Worst Masterpiece." One of the more colorful phrases among its familiar arguments about cultural appropriation and its failure to be real jazz is that it "clogged the arteries of American music." This is just the latest in a century's worth of invective against the work, which has nevertheless managed to survive as the most recognizable and emblematic piece of American concert music - which, as it turns out, Gershwin had to be tricked into composing, and only had a month to do so. Any blame for the controversy surrounding the piece, it should really be laid at the feet of Paul Whiteman.

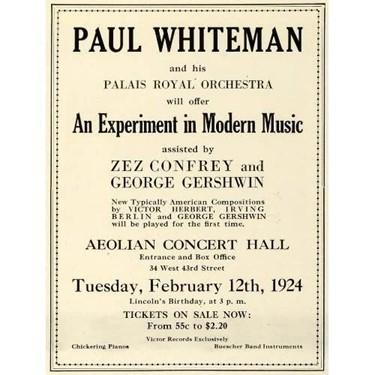

Whiteman was the foremost bandleader of his time, and became known as the King of Jazz, even though he began his career as a classical viola player and led tightly controlled performances that rarely incorporated improvisation. It was his idea to mount a concert billed as “An Experiment in Modern Music” on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, a date specifically chosen to highlight the connection between the Emancipation Proclamation and the advent of America’s preeminent native art form. The concert consisted of pieces that combined elements of classical music and a mannered stylization of “jazz” that bore little resemblance to the wild counterpoint of the New Orleans Dixieland bands that started it all. It was also not a particularly original idea, or a necessary one: by 1924 Milhaud had composed his groundbreaking jazz-tinged ballet La Création du monde and Stravinsky had subjected jazz to his own form of musical cubism in L’Histoire du Soldat. The secret of jazz had long been out, and the European musical establishment was already far more impressed by it than by the Americans like George Chadwick and Arthur Foote who still dutifully wrote Brahmsian symphonies. For that matter, the kind of cultural symbiosis he envisioned by an American composer had actually already manifested a full half century before jazz even existed in the person of Louis Gottschalk, a Creole composer and virtuoso pianist who incorporated the music of African slaves and the dance forms of Cuba and Puerto Rico into music for piano and orchestra.

So there was no real reason for Whiteman to conduct this “experiment”; by this time, jazz didn’t need anyone’s stamp of approval. The concert was more a promotional vehicle for Whiteman than anything else, which is probably why Gershwin politely declined when he was asked to write a concerto-like work for the concert with himself as soloist. It was only when Whiteman, refusing to take no for an answer, advertised the concert as containing a new work by Gershwin that he realized he had no choice but to take this opportunity, leaving him only five weeks to compose the work.

The initial ideas for the piece came to Gershwin while he was on a train to Boston, which might explain the work’s slow churning start, its propulsive rhythms, its sense of traveling through different landscapes, and its grand feeling of arrival at the end. While it’s clear that Gershwin helped himself to African American jazz idioms, he also stole from music he did have a birthright to, Klezmer (the unmistakable influence for the iconic clarinet glissando that begins the work) and the Russian orchestral tradition of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff.*

Which is not to say that a crime wasn’t committed, because it was - not by Gershwin himself, but by the musical establishment (beginning with Whiteman) who treated the work as the culmination of a cross-cultural conversation instead of the beginning of one. It wasn’t Gershwin who declared that a piece he dashed off in a month, didn’t orchestrate himself, and for which there is no definitive version, should be regarded as the ultimate statement of American music. But the problem was that Gershwin made continuing that conversation difficult because even this sloppy, disjointed work from the beginning of his career was simply too good and became too popular for another composer to answer or engage with, and many tried to do so.

The most successful subsequent attempts to marry jazz with symphonic music took a different approach. Duke Ellington created big band arrangements of classical music (like his justly famous version of the Nutcracker Suite), and eventually wrote his own symphonic masterwork, Black, Brown and Beige, which might be the greatest fulfillment of Dvořák’s assignment to date. Miles Davis recorded a selection of songs from Porgy and Bess that reclaims the real jazz at the root of Gershwin, producing one of his greatest albums. Charles Mingus produced a work over two hours long called Epitaph in which the synthesis of styles reaches its full maturity; the novelty is beside the point as it explores emotional depths.

The legacy of Gershwin and Rhapsody in Blue continues to be complicated. The fact that it’s still raising hackles should not be seen as a condemnation of Gershwin but of the fact that racial issues are still a painful open wound over a century and a half after the Emancipation Proclamation. Let’s all hope that when the piece celebrates its two hundredth anniversary, which it surely will if there is still a civilization with symphony orchestras, people of all backgrounds can set aside their long-forgotten conflicts and enjoy this delightful work by an inconvenient genius.

*This aspect of Gershwin’s work was explored by DC’s own Post-Classical Ensemble in their 2010 program Russian Gershwin. On Monday night following the PBS NewsHour, David Martosko will be airing their extraordinary interpretation of Rhapsody in Blue from that performance, featuring Russian pianist Genadi Zagor performing his own improvisations on Gershwin’s solos along with the original Ferde Grofé orchestrations used in Paul Whiteman’s 1924 concert.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.