Editor's Note: Critically-acclaimed violin soloist Rachel Barton Pine writes this guest blog, speaking about her foundation's initiative, Music By Black Composers.

In 1997, I was invited to record my first concerto album. As I was quite young, I decided to wait a little longer before doing major concertos like Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Beethoven (all of which I’ve since recorded). Instead, the plan was to find some overlooked but wonderful repertoire for violin and orchestra. Thanks to the African-American conductors active in my hometown of Chicago when I was a teenager – Michael Morgan, Paul Freeman, and Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson – I was aware that there were numerous fantastic works by composers of African descent going all the way back to the 1700s. As a fan of the violin, I was really excited by the idea of introducing violin repertoire to the public which would be new discoveries for almost everyone.

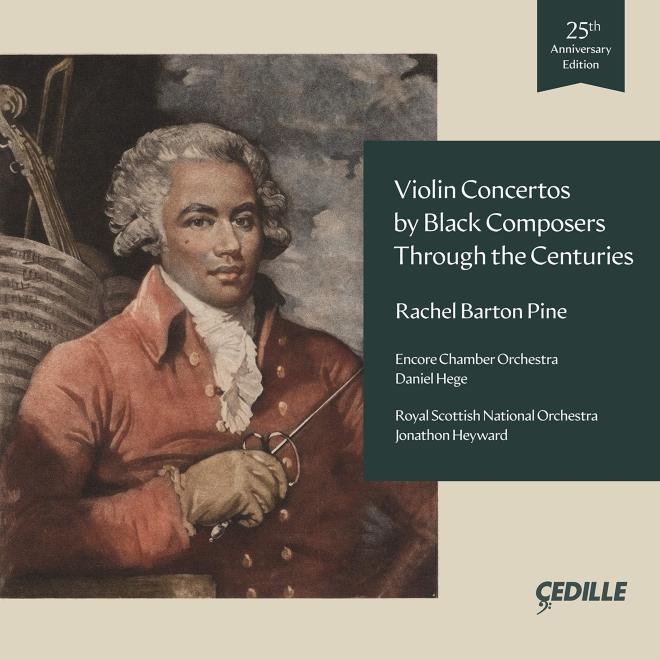

During one of my excursions to a library archive, I saw a huge replica of an historic painting on the wall – a Black man in an 18th-Century wig with a sword and a violin. Whoa! Awesome album cover alert! Of course, it was Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, and I fell in love with his music. I included his Violin Concerto in A Major on my album, Violin Concertos by Black Composers Through the Centuries, alongside works by José White and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (and now Florence Price, in the 25th anniversary re-release).

When I released this record, I was just thinking, this is gorgeous violin music that should have been part of our canon all along, and I’m excited to share it! Almost immediately, I started receiving numerous requestions from students, parents, and teachers, asking for more of this repertoire.

There have been so many phenomenal Black music researchers throughout the decades, but most of what they’ve done has been within academia. For a long time, this music and history just didn’t filter down to the average student in the average American town. African-American children didn’t have access to any student-level works by Black composers, nor did they know that there were all-Black orchestras in America in the 1800s, or that Frederick Douglass and Coretta Scott King were serious violinists. The perception from many families was that classical was someone else’s music.

So in 2001, my not-for-profit Rachel Barton Pine Foundation started its Music by Black Composers (MBC) initiative. Gathering the sheet music was quite an adventure, including visiting libraries in different countries, contacting composers’ descendants, and digging through unsorted boxes of manuscripts at HBCUs. We ended up collecting and evaluating more than 900 pieces by more than 450 women and men from the 1700s-2000s, from Africa, Europe, North and South America, and the Caribbean.

MBC’s first efforts were focused solely on providing resources for students, with our first releases occurring in 2018 – curricular volumes for individual instruments, starting with the violin, a coloring book that features 40 of the most important Black composers from the 18th-21st centuries, and a timeline poster that features more than 300 Black composers from around the world. It has been really inspiring to witness the excitement from students and teachers of many different races and ethnicities as they discover these composers and their beautiful pieces, many of which have quickly become favorites. Many further volumes are planned, including music for ensembles.

Thanks to suggestions and requests from colleagues, we have vastly expanded the free resources on our musicbyblackcomposers.org website. Many of these pages are useful to performers but also relevant for music lovers. They include repertoire directories, a living composers directory (350+), an historic composers directory (150+), a list of children’s books about Black classical music-making, a bibliography of reference books on Black classical composers, a discography of works by Black classical composers, a list of podcasts and radio programs that celebrate Black classical composers, downloadable presentation materials to aid interactive performances, and even links to articles and videos about music theory as it pertains to Black music history. Please check out the MBC Projects Timeline in the “About” tab on our website for more details about all of our plans.

The omission of the composition of Black composers from our curricula and concert halls silences a rich vein of musical creation from global cultural consciousness. The effects of this erasure are most serious for aspiring Black classical musicians. Without access to the historic narratives of Black composers, these young musicians struggle to become part of an art form in which they do not appear to belong. The ultimate result is a lack of diversity in our concert halls, both on stage as well as in the audience.

By changing the story about the music of Black composers, we want to help children be able to dream their dreams in the first place, and for those dreams to resonate throughout our communities and beyond.

For many years, efforts to gain greater recognition for this repertoire by the classical music world in general were somewhat ignored and dismissed. But recently, there has been a sea change in the industry. From the biggest orchestras to the smallest presenting series, decision makers are finally eager to share programs that feature greater diversity and inclusion. Schools and teachers everywhere are revising their curriculums to better reflect their values.

It's an exciting time to be a classical music fan! We’re being introduced to fascinating new discoveries every day. I firmly believe that, had they been given a fair chance, many of these great works would have been among the most popular all along. Celebrating this music is not only about justice, inclusion, and representation. Classical music is one of the greatest expressions of our shared humanity, and our art form can only continue to thrive and grow if all of our voices are heard.

I’m thrilled to be returning to D.C. on April 19 for a performance at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater as a part of Washington Performing Arts’s season. I’ll be playing some of my favorite music: masterpieces by African-American composers Dolores White, Billy Childs, and William Grant Still, alongside Beethoven’s Sonata No. 9, written for the legendary Afro-European violinist George Bridgetower, and Dvorak’s Sonatina, inspired by his encounters with African-American spirituals. See you at the concert!

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.