Tár is a film that did its homework. Writer and director Todd Field, himself an accomplished jazz trombonist, strove for verisimilitude in this story about the abuse of power in the world of classical music. Cate Blanchett (playing the conductor Lydia Tár) really plays the piano, the celebrated German actor Nina Hoss (playing Lydia’s wife Sharon) plays the violin, cellist Sophie Kauer makes her acting debut as Olga (with a Russian accent no less!), and musicians from the Dresden Philharmonic, standing in for the Berlin Philharmonic, not only play but really respond to Blanchett’s conducting. The film is committed to every detail.

But despite their best efforts, there are a couple of inaccuracies, as well as some niche references that are obscure even for many familiar with this world, so let’s clear some things up for those planning on seeing the film (or who already did but are still a bit confused.)

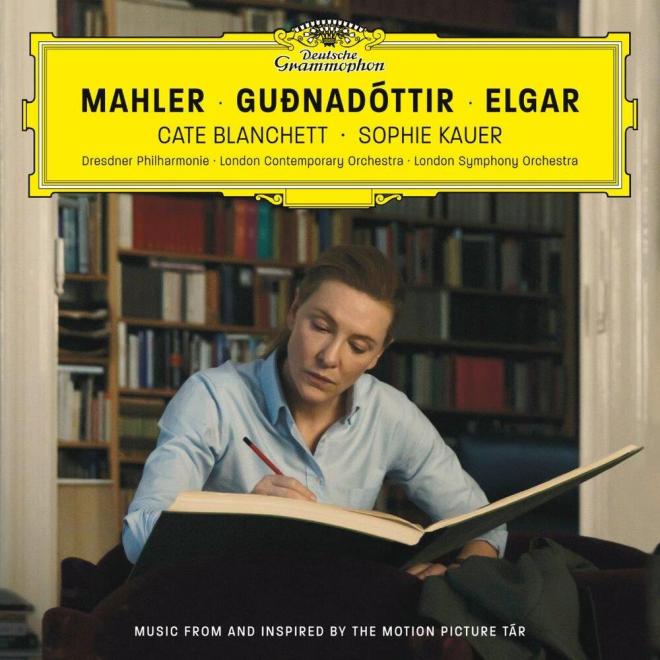

First of all: Lydia Tár is a fictional character in a fictional story that intersects with the real world. The film begins with Tár being interviewed at a New Yorker Festival by the real Adam Gopnik. We learn that Tár is a few weeks shy of her fiftieth birthday, is about to take over the directorship of the New York Philharmonic, but first has to complete recording a cycle of Mahler symphonies with the Berlin Philharmonic. She has commissioned works from real-life composers Julia Wolfe, Jennifer Higdon, Caroline Shaw, and Hildur Guðnadóttir (the actual composer of the film's soundtrack.) In discussing her place in the realm of women conductors, Tár names Marin Alsop, Joanne Falletta, Laurence Equilbey and Nathalie Stutzmann as her contemporaries. She also delivers mini-history lessons about the "women who did the real lifting", Nadia Boulanger and Antonia Brico.

In that same scene, Mahler's Symphony No. 5 is referred to as "the big one" and it’s implied that it’s the most difficult and intense of the cycle. Here is our first inaccuracy. It's certainly distinctive and well-loved; Leonard Bernstein is now in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery with the score of Mahler's Fifth lying on his chest (a fact that I'm surprised is not mentioned in this film, since Tár says Bernstein was her mentor and we see a brief glimpse of one of his Young People's Concerts.) But no one would call the Fifth (which is how it's generally referred to, not "the Five" as Tár calls it) a "bigger" symphony than the Second (aka the "Resurrection"), the Third, or the Eighth (aka "Symphony of a Thousand"). Nor does it stare into the abyss of mortality and despair as deeply as the Sixth or the Ninth. The Fifth, as befits its number, is solidly in the middle of the pack in terms of its ambitions, and it might even owe its popularity to its depiction of a human-scaled emotional landscape rather than an apocalyptic vision of the cosmos.

The Fifth also contains what is probably Mahler's most well-known individual movement, the Adagietto. As is mentioned in the film, the movement has acquired an association that is quite different from the one intended by Mahler, who wrote it as a musical love letter to the woman who would become his bride, Alma. The fault for this lies squarely with Bernstein, who introduced the piece to millions when he conducted it at the funeral for Robert Kennedy. (You can see Bernstein discussing and conducting the movement below.)

It was a beautiful gesture, but it gave rise to the idea that the piece was about grief, which was reinforced a few years later when it became even more famous for its appearance on the soundtrack to the Luchino Visconti film Death in Venice (which is why, when we see Tár rehearse this movement with the Berlin Philharmonic, she urges the musicians to "forget Visconti.")

As a result of these two intersections of this movement with the zeitgeist, a generation of conductors grew up emulating Bernstein by stretching its playing time to over twelve minutes, when according to all reports the movement came in under eight minutes when Mahler himself conducted it, as it does in the recording posted below conducted by Mahler's close pupil and assistant Bruno Walter. This is what Tár means when she says that by conducting it at a faster tempo, she is "choosing love."

One of the people who first drew attention to this tempo discrepancy was a rich businessman and amateur conductor named Gilbert Kaplan, who is the clear inspiration for a character in the film named Eliot Kaplan. The real-life Gilbert conducted the Adagietto, recording it with the London Symphony at the faster tempo at a time when the slower tempo had become the norm. The fictional Eliot is a rich dilettante conductor who partners with Lydia Tár to create a foundation that supports young women conductors. He’s scheduled to conduct Mahler’s Third Symphony and begs Tár to let him look at the notes she made in her score of the work. She refuses, but does give him one piece of advice regarding the lush and passionate last movement (subtitled What Love Tells Me, which is referenced in the film): "free bowing”, in which each string players determines their own phrasing, which can create an incredibly rich sonic tapestry (even if, as Tár admits, it's a bit disorienting to watch.)

We get a lot of glimpses into the inner workings of the Berlin Philharmonic. It’s a bit ironic that Blanchett’s character, the conductor Lydia Tár, says at one point that “an orchestra is not a democracy,” because Berlin is one of the few major orchestras in which the musicians actually can vote on various issues including who conducts them. But democracy stops once the conductor is on the podium.

This film comes out at a time when there have been significant cultural shifts in the classical music industry. While there is still a long way to go when it comes to real parity, it finally feels normalized to see non-white, non-male musicians represented both on the podium and on the concert program. As great as the movie is, it feels dispiriting that when Hollywood finally turns its attention to classical music, the issue of representation is depicted in such a cynical light. And it’s also misleading, because the sad fact is that the abuse of power that continues to exist in this field is – still - overwhelmingly committed by men.

The movie I really want to see is one that actually celebrates diversity in classical music. When is that coming out?

Learn more about what a conductor does!

More about the life of Leonard Bernstein

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.