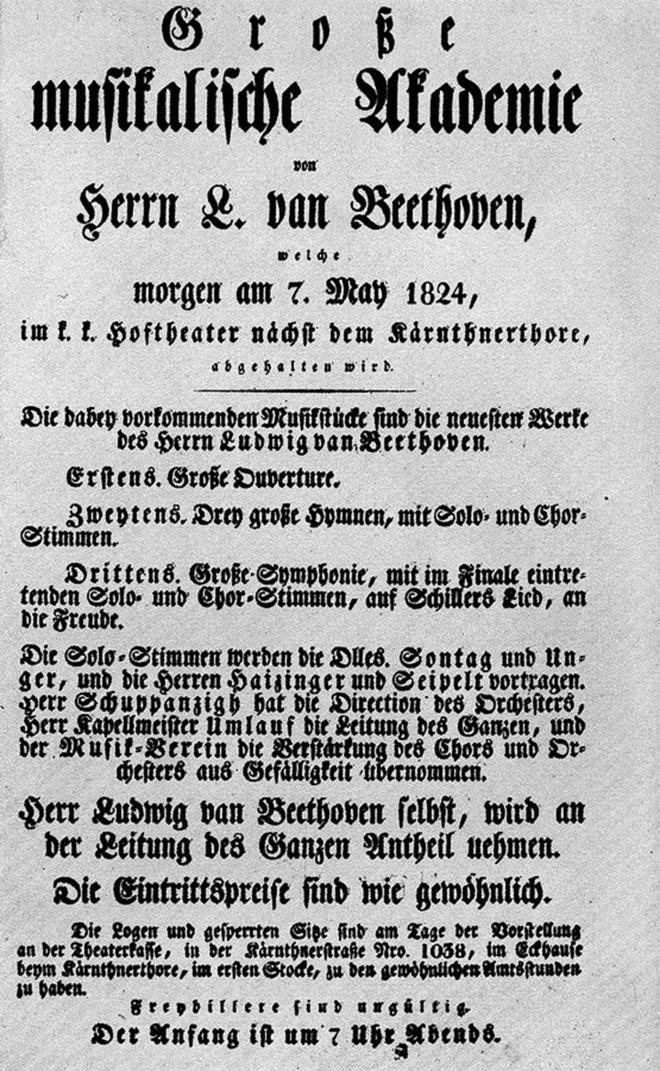

The concert (aka “Grand Musical Academy”) that included the world premiere of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony took place on Friday, May 7, 1824, at 7 pm, at the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna. (Coincidentally, this was ten years to the month after Beethoven’s Fidelio, in its final revised version as performed today, also had its world premiere in the same theater. In the 1870s the theater was razed and replaced with the Hotel Sacher, home of the Sachertorte, which some pastry chefs would claim is the Beethoven’s Ninth of desserts. Discuss.) The program began with the Consecration of the House Overture, a festive work full of neo-Baroque flourishes that Beethoven had written two years earlier for the opening of the Josefstadt theater, and continued with three sections of his Missa Solemnis (Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei) performed in German to satisfy Vienna’s ban on performing liturgical works in a public secular space.

The exact size of the orchestra is in dispute. As someone who is not a credentialed musicologist, I am amused by how those who are don’t agree on the details. A document listing the personnel mentions “twelve basses and cellos” which some scholars take to mean 6 cellos and 6 basses, while others insist that there were 12 cellos and 12 basses! The former numbers, while more plausible, seem a little skimpy in proportion to the rest of the orchestra, and while the latter seems outrageously large, Beethoven did like to use an unusually robust bass section when he could afford it, since that enabled him in his deafness to feel the vibrations. The rest of the orchestra consisted of 24 violins evenly divided into first and seconds, ten violas, winds mostly two to a part for a total of 4 flutes, piccolo, 4 oboes, 4 clarinets, 4 bassoons, contrabassoon, 8 horns, four trumpets, alto, tenor and bass trombones, timpani, triangle, cymbals and bass drum. The chorus seems to have numbered about 80, and there were four vocal soloists.

One of those soloists was the 20-year-old contralto Caroline Unger. She was one of those historical figures who crossed paths with many other historical figures: her first voice teacher was Aloysia Weber, Mozart’s sister-in-law and first love; she made her stage debut in 1821 playing Dorabella in Così fan tutte, in preparation for which Franz Schubert served as her accompanist and vocal coach; upon hearing her sing in Paris in 1833, Rossini declared that she possessed “the ardour of the South, the energy of the north, brazen lungs, a silver voice and a golden talent”; and that ardour apparently extended to her personal life as well, as evidenced by her steamy affair with the writer Alexandre Dumas on a boat in Italy in 1835. Bellini and Donizetti both wrote roles for her. She retired in 1843 after an extraordinarily successful career for the time, and died in 1877.

But as it turns out, what she is best remembered for has nothing to do with her talent or her glamor.

Three people presided over the performance on May 7: the concertmaster (i.e. the principal violinist who in those days took a much more active leadership role than is the case today) was frequent Beethoven collaborator Ignaz Schuppanzigh; the conductor was Michael Umlauf (who had also conducted that Fidelio premiere a decade prior); and Beethoven himself. Umlauf had discreetly warned the musicians not to follow the composer. Beethoven insisted on conducting as well, which perhaps served as a kind of interpretive dance to transmit the music’s meaning from its creator, but the musicians probably ignored him as they buried their heads in their difficult parts and looked to Umlauf to keep them together. Whatever they did worked, and the performance was a triumph. At the end of the final movement, Beethoven was still furiously conducting, not having been able to hear that it was over. Caroline Unger gently turned him around so he could see the enthusiastic standing ovation.

And with that simple, humane gesture, she demonstrated the symphony’s legacy on a number of levels: a show of affection and respect toward the composer, who had endured a half century of being abused, ridiculed and misunderstood just to finally experience the public acceptance and adoration of one of his most challenging works, and a public embrace of someone whose physical challenges effectively excluded him from society. Indeed, that gesture was more inclusive than the Ode to Joy itself; it should be admitted that Schiller probably wasn’t thinking of women or deaf people when he wrote “Alle Menschen Werden Brüder” or his second verse:

If ever you have known a loyal friend

To whom you have repaid your truest faith,

If ever you have found a loving spouse,

Come sing with us and share your jubilation!

All who with a kindred soul have forged a bond

That no impediment can break, come sing!

Those who will not share their lives with others

Must turn away while weeping lonely tears.

For two centuries we have turned to this work to remind ourselves what it is we really want from civilization, from art, and from ourselves. The sentiment of the poem and Beethoven’s treatment of it simultaneously feels like a utopian aspiration, a bitter rebuke to our failure to stop violence and war, and a challenge that inspires us to action. It has been co-opted by various regimes, democracies and dictatorships alike, and is currently the anthem of the European Union, but it has outlasted any political use to which it has been put. What endures is an hour-long journey from terrifying depths to euphoric heights that speaks to all of us as we all struggle and strive towards joy.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.