Editor's Note: You can enjoy Monteverdi's Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda on WETA VivaLaVoce's Opera at 8 on February 24.

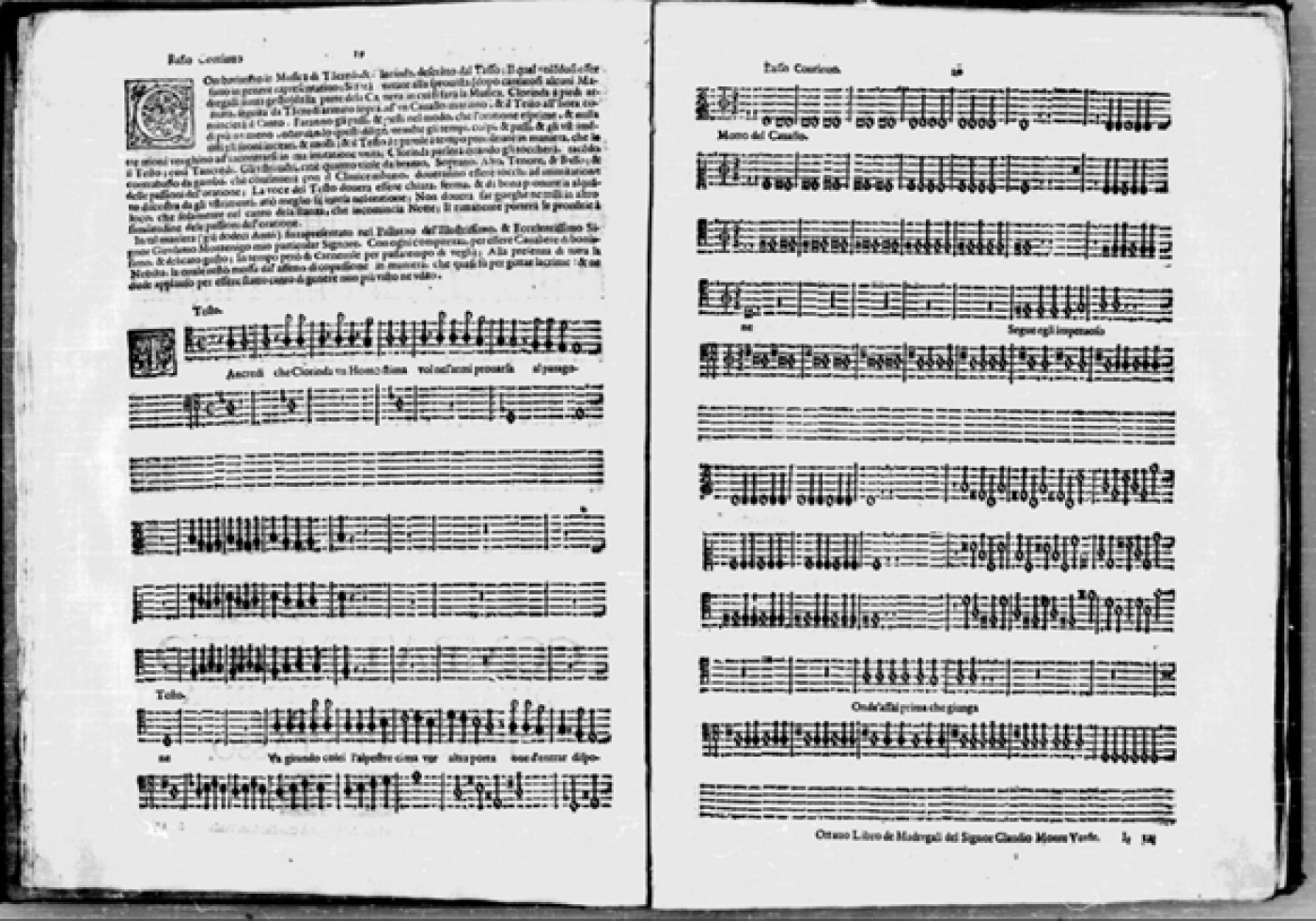

This year marks the 400th anniversary of a groundbreaking work by Claudio Monteverdi: Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. Monteverdi called this piece a madrigal, but by the time he assembled his eighth book of madrigals in which this is included, the term had been stretched to the point of no return. His earliest madrigals were brief settings of love poems for a small group of unaccompanied solo voices that were just a few minutes long. They eventually became more elaborate and diverse, employing instruments, having the voices engage in dialogue with one another, then having these voices inhabit distinct characters, and finally, in the eighth book, we have madrigals with stage directions, ballet sequences and fight scenes, essentially short operas. (The eighth book of madrigals is subtitled “Songs of War and Love,” but really they’re all love songs, since the warlike images are intended as metaphors for the struggles in romantic relationships.) Il Combattimento is not quite an opera, since the main voice we hear is that of a narrator, while the two title roles have relatively little singing and spend most of the piece pantomiming the story.

The world premiere of this piece took place on the last day of Carnival season in Venice on February 24, 1624, which that year fell on a Saturday just as it does this year. That performance employed not only three singers and six or seven instrumentalists, but also a live horse, and the production must have employed an equestrian trainer since the stage directions specify when the horse engages in different types of movements, which are reflected in the music. We can only imagine the effect it must have made for the audience, settled in for a concert of vocal chamber music, to have two performers come into the room in full armor, one of them on horseback.

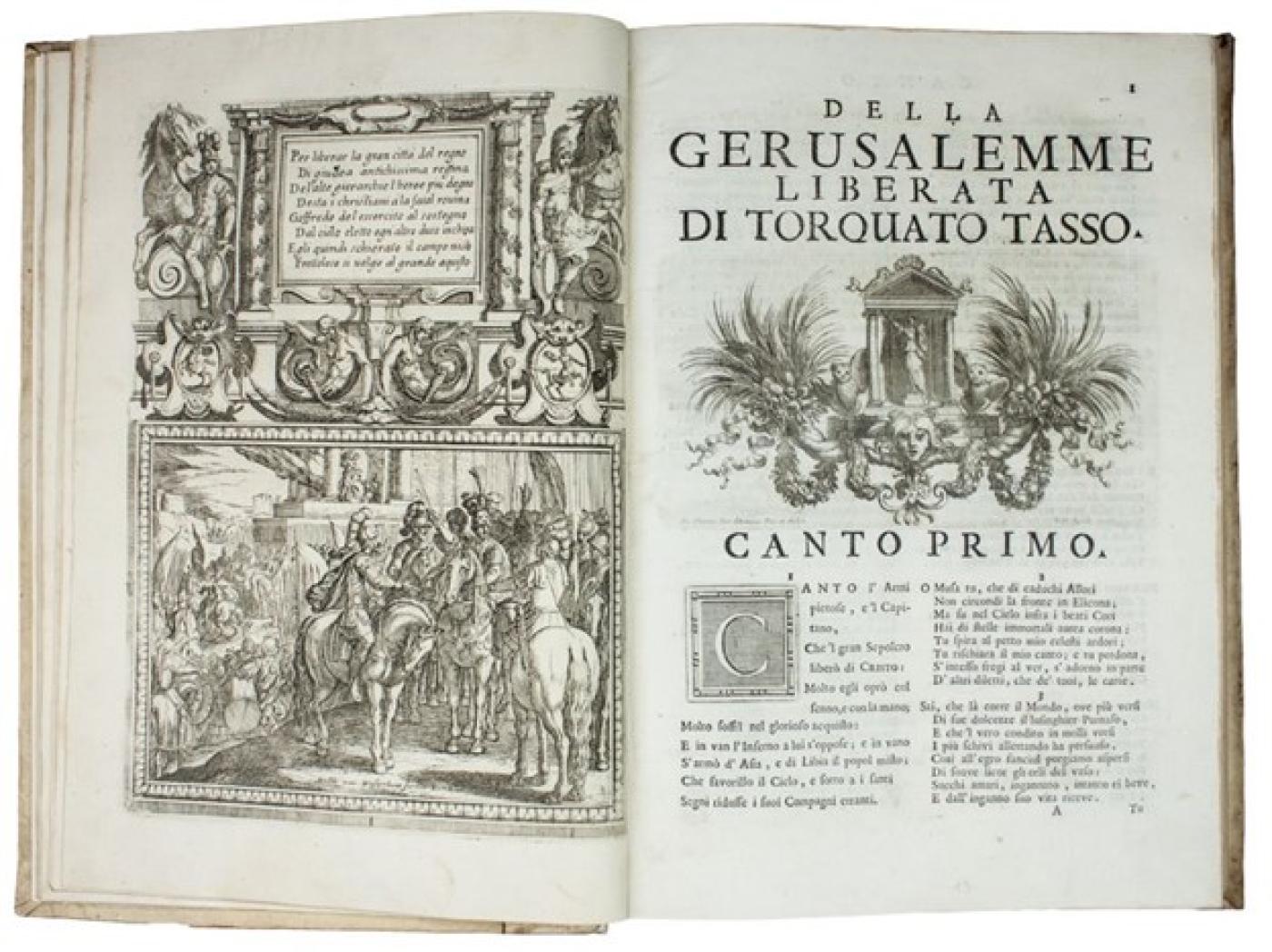

The story is taken from an epic poem called Jerusalem Delivered by the 16th century Italian poet Torquato Tasso, the source for many operas and cantatas throughout the entire history of classical music, including the various works called some variant of Armide (by, among others, Lully, Gluck, Salieri, and Dvorak), Rinaldo (Handel and Brahms) and Tancredi (the Monteverdi and Rossini works we’re playing on WETA VivaLaVoce this Saturday night.) (There are also works that dramatize the life of Tasso himself by Donizetti and Liszt.) Jerusalem Delivered tells stories about the First Crusade from the final years of the eleventh century, in which Christian knights battled Muslims for control of Jerusalem.

The story the Monteverdi work tells is about the knight Tancredi and a woman soldier from the Muslim army named Clorinda who surreptitiously met off the battlefield and fell in love with one another, but they unknowingly met in battle at night while both were in full armor and could not recognize each other. They engage in a series of duels, breathlessly described in graphic detail by the narrator, until finally Tancredi delivers the death blow and in the end discovers to his horror that he has killed his beloved. He acts according to the knight's code of honor, removing her helmet and baptizing her with water from a nearby stream, and Clorinda gets the final word, singing "Heavens open, I go in peace," in one of the most transcendent moments in all of music.

This 24-minute work is a landmark in many respects. In coming up with ways for the string ensemble to depict the violent duels, Monteverdi pioneered effects that would later become standard in the modern orchestra, such as pizzicato, in which the players pluck their strings instead of bowing them, and tremolo, in which the players move their bows rapidly back and forth on a single note. Remember that this was a full century before Vivaldi used these effects in the Four Seasons, and they continued to be used by everyone from Beethoven to Bartok; they all owe a debt to Monteverdi. As for the voices, they are called upon to express themselves in ways that wouldn't become commonplace for two centuries, having more in common with Rossini and Verdi than anything in the Baroque or Classical eras. While it could be debated whether this work can be considered an opera, it established a vocabulary for operatic expression whose influence is still felt to this day.

Here is the complete text of the work, translated by M.J. Beasi:

Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda

Clorinda, armed and on foot, followed by Tancredi, armed, on a Marian horse, enter unexpectedly (after some madrigals without action have been sung) from the side of the room in which the music is performed, and the narrator will then begin the singing….They will perform steps and gestures in the way expressed by the oration….observing diligently those measures, blows and steps, and the instrumentalists; sounds, excited or soft.

NARRATOR:

Tancredi, blind to see who stands before him

Seeks to challenge Clorinda to brutal battle.

Stealthy, she creeps around the twisted mountain,

above the city, to where its gate is hidden.

His blood thirst overtakes him, so intent is his pursual

In haste, he scrapes his armor loudly, it clatters and clashes and crashes loudly

She whips around to face him

CLORINDA:

“Hold, you! What news do you bring to me?”

NARRATOR:

He answers:

TANCREDI:

“War and death, I bring you.”

CLORINDA:

“Only war and death,”

NARRATOR:

She says:

CLORINDA:

“Fear not, I won’t refuse them to you, if that’s what you seek so dearly.”

NARRATOR:

Hungry Tancredi, seeing that his foe is just as eager for battle, stands tense and ready.

Each savagely grasps hold of a sharp sword,

their eyes blazing with pride and burning fury;

Then shifting slowly...

Lingering steps between them...

Jealous bulls at the ready

ablaze and angry

Nighttime, you who envelope our dear warriors,

grasped closely, held to your breast, guarded in shadow

Worthy of brightest light, Worthy to stand on

the great stage, to be remembered in full glory.

(Sinfonia)

Please, would you let me draw forth in brightest sunlight

for our future descendants—please—their story

Long live their names in lore, in brightest glory

Your darkest splendor shines all through our mem’ry

No defense, nor retreat, no careful planning,

no clever feet, no thought of skill or training.

Both thrust wildly, full attack without relief.

Darkness trumps any art, bloodthirst is raging.

Blade upon blade sings!

Weapons horribly clashing!

Each striking hard, mid-blade, without ceasing,

Feet planted staunchly, none retreating.

Standing so strongly, a blur of arms in action

No blade descends in vain, no thrust betraying.

Shame turns to anger, and anger into vengeance,

Vengeance taken gives way to a new cause for shame.

Each blow feeds upon the last in a never-ending fury,

Ev’ry strike a new wound so filled with hatred.

Moving in ever closer, closing in, further closing in,

’til their blades are clearly useless,

Hitting, and butting, roughly they scrapple,

So crudely, shoulder hitting shoulder, crushing each other.

Three times he squeezed her tightly,

squeezing, crushing, and still three times he lost her,

each time she breaks his hold,

twisting and then pushing back fiercely, she spurns his embraces,

knots of hate, so unlike those of a lover.

Swords again clashing, steel blades are crashing,

each whet with blood, furiously stabbing,

once and again they’re wounding.

exhausted, breathless and panting

each must finally retreat into the shadows

to gasp for air and to receive some respite

They eye each other, resting their broken bodies,

so weakened from the loss of blood, swords yet gleaming.

Now the last light of nighttime’s dimming stars

makes way for dawn, breaking with sunlight.

By this light, Tancredi beholds Clorinda’s brightly streaming blood,

while his own is fairly drying. So proudly,

how this does please him, Oh!

Oh, how vain our hearts and how foolish is our pride, fanned by fortune.

Misero, wretched hero, Oh sorrow is the only prize

that this triumph can ever bring you.

Should you leave here alive,

Your eyes will pay for every drop of blood you have spilled with sea of tears.

These tired warriors, so brave and bloodied,

standing still and silent, their battle thus deferring.

Finally, it was Tancredi broke the silence,

seeking to name the blade that so defied him.

TANCREDI:

Sure, it is misfortune that such valor should hide in silence,

under cover of darkness.

But since unlucky fate dares to deny us the praise

and the glory that so befits our deeds

Then if words have a place in warfare,

would you tell me your home, your allegiance, and your name,

that I may know, should I die, or should I triumph,

whom I have conquered, or who will honor my death?

NARRATOR:

Ferociously she answered:

CLORINDA:

In vain you ask me for that which I will surely never tell you.

But, whatever my name, you see before you

one of those who has burned your tower.

NARRATOR:

Tancredi heard these words and blazed with raging:

TANCREDI:

You’ll be sorry you spoke such!

Both your silence and your outrageous words incite me.

Vengeance on such a beast will so delight me!

NARRATOR:

Anger now in their hearts serves to renew them

Weakened now, yet into their fiercest battle

all skill and strength are long departed,

only fury remains now to refuel them.

Oh, what a wide and bloody opening

are each of their blades revealing,

here, and then there, as they are swiping

And if their lives fail to leave them,

’tis only anger gripping tightly.

Ah! But alas, now is the fatal hour

that life must leave the breast of dear Clorinda.

He drives his sword into her precious chest,

the blade plunges deep, quenching its thirst with her warm blood.

Her garment, made with golden embroidery,

that confined her tender heart within its folds,

now with red is flooded.

Ah, yes, she feel’s she’s dying,

Her weakened body and weary feet will fail.

He pounces on his vict’ry,

threatening further now, he tightens his hold upon the maiden.

She, now while slowly falling, voice full of such sorrow,

speaks weakly, her final wishes,

such wishes, such wishes, now born of a new and tender hope.

Hope of a generous and faithful spirit,

hope God bestows upon her,

for if in life her heart did rebel,

she will have faith in heaven.

CLORINDA:

Amico, I’m beaten. Forgive me now, as I have forgiven,

No, not this shell, which knows no torment,

Forgive my soul. Please, pray for me now,

And please wash away my wrongs, with the purest water.

NARRATOR:

Resounding in this languid song, such soft words,

such a sad and tearful pleading,

Ah, but his heart has nearly broken apart, relenting.

His anger flown away, tears of pity flow.

Ears now drawn to a murmur from the mountain,

for it seems there a small stream softly tumbles.

There, he runs forth with his helmet, to fill it.

Then he returns, now prepared to do his duty,

and then with trembling hands, he slowly lifted

the cover from the face beneath, yet unknown to him.

But what is this, then? This face familiar?\

He, in that moment, struck speechless and frozen.

Ahi vista! Ah! What unhappy sight!

He did not die, but gathered up his last strength,

and held it tightly to guard his broken heartstrings

Torn with grief, he pushed back all his anguish

to tend to his beloved, the one who, by his sword, was killed.

And as the knight recites the words so holy

She is transfigured by such joy, her face shining.

As her life wastes away, her joy increases,

softly singing:

CLORINDA:

Heav’n awaits, I go now in peace.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.