How Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture came to be associated with the Fourth of July isn't exactly a mystery - the blame/credit clearly goes to Arthur Fiedler, the longtime conductor of the Boston Pops - but it has come to feel like one of those cultural oddities that one just accepts without question, like the mixture of ethnic borrowings that resulted in Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny and Valentine's Day and Halloween and the Thanksgiving menu. ("Mommy, did the Wampanoag really put marshmallows on their sweet potatoes and did either of those foods exist in Plymouth in 1621?") But, at a time when Americans are thinking more deeply about issues pertaining to culture and identity, and when Russia's invasion of Ukraine casts a dark shadow over a seemingly innocent use of music composed to celebrate Russian military might for a celebration of American freedom and independence, it seems like an apt time to question this particular tradition and contemplate what music we could use in its place.

But before we go forward, let's go back, as we who love classical music like to do. First of all, we should acknowledge Tchaikovsky's place in American culture. One of his most famous works, Piano Concerto no. 1, received its world premiere in Boston in 1875, where it achieved instant success (unlike the more problematic reception that would greet it in Russia a few months later). In 1891, Tchaikovsky conducted the concert that opened Carnegie Hall, of which he said "I had a royal welcome...America knows me better than Europe." And it was the ballet companies of San Francisco and New York City that established The Nutcracker as a holiday staple (not long after Walt Disney introduced generations of children to its suite in the movie Fantasia.)

And it was in Tanglewood where it became a summer tradition to perform the 1812 Overture with fireworks - not for the Fourth of July, but for its annual celebration of itself in the first week of August, "Tanglewood on Parade." Arthur Fiedler conducted the 1973 Tanglewood performance, which inspired him to include it in the program of the 1974 July 4th Pops concert on the Esplanade in Boston (the same month in which the melody of the slow movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony reached #1 on the American pop music charts in the form of John Denver’s “Annie’s Song”.) This is turn inspired a prominent Boston millionaire to offer to bankroll a spectacular performance of the 1812 for the 1976 Bicentennial Esplanade concert that would include the cannons and artillery included in the original score (which, due to changing circumstances soon after its commission, Tchaikovsky himself omitted in his own performances of the work.) Fiedler instructed the military personnel operating them to ignore Tchaikovsky's rhythmic indications and just "let all hell break loose." It was such a hit that it has been repeated in Boston every year since and was quickly adapted as a July 4 tradition by many other American orchestras. As I said, it's not a mystery how this all got started, and we even have the receipts.

So this "tradition" is only 48 years old. It shouldn't feel blasphemous to suggest changing it, and with the country's 250th birthday coming up in two years we have the perfect occasion to do so and just enough time to plan for making this change. (That's assuming we can agree on what to call it: Semiquincentennial? Bisesquincentennial? Sestercentennial?) With all due respect to Tchaikovsky, he will have had his half century of scoring the United States’ birthday celebration, and it’s time to pass the torch.

Before I get to my choice for the new July 4 fireworks music, I should mention that there’s another work by a 19th century Russian composer that would fit the bill surprisingly well. Alexander Glazunov, who was 25 years younger than Tchaikovsky and developed a mutually respectful relationship with the older composer that has been compared to Mozart’s relationship with Haydn (and who went on to take the Haydn role with his student Dmitri Shostakovich), was commissioned to write a work for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, tp which he responded with the Triumphal March - which essentially does for the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” what the 1812 Overture did for “God Save the Tsar”. The work’s final two minutes are just as bombastic as the corresponding passage in the 1812, and it’s in the service of a melody that all Americans know and love even today – in fact it’s probably the only American patriotic song that truly transcends ideological boundaries and is embraced by all. And you could certainly add a bunch of cannons without doing any aesthetic damage to the music. It would, in many ways, be the perfect replacement for the 1812 Overture.

But maybe that “perfect replacement” is not what’s called for. Maybe what we want is a piece by an American that was composed in the wake of our own wars and national traumas, one that acknowledges the struggle while also celebrating our values. It should embrace hope not as an excuse for empty displays of sentiment but as a brave stance of commitment to the future regardless of the obstacles.

And it should also have a familiar American tune with a big loud extended ending that you can hear through the fireworks.

To that end I humbly submit my proposal for the new orchestral piece to serve as the climax to our July 4 celebrations:

The finale to Symphony No. 3 by Aaron Copland.

As it happens, this piece, like the 1812, opens with a quiet hymn-like statement of the main theme we all recognize, but after a minute we get the full statement of the theme in its original scoring for brass and percussion.

That theme? Fanfare for the Common Man.

The Fanfare was written in 1942 in response to a commission from the Cincinnati Symphony for a series of short works by American composers to begin each of its concert programs, a musical acknowledgement of - and spiritual contribution to - the war effort. Both the title and the music were inspired by a speech given by Vice President Henry A. Wallace called “Century of the Common Man” which began:

This is a fight between a slave world and a free world. Just as the United States in 1862 could not remain half slave and half free, so in 1942 the world must make its decision for a complete victory one way or the other.

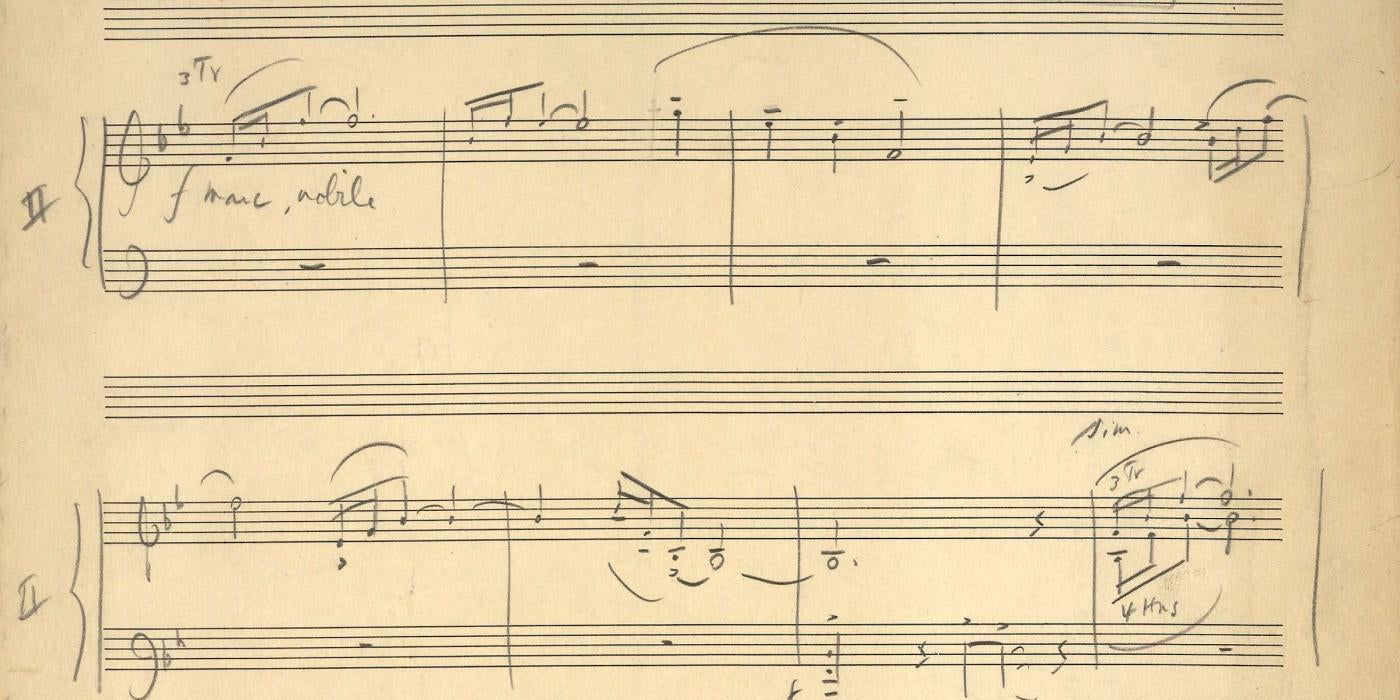

Copland wrote his Symphony No. 3 in the years 1944-46, and he acknowledged that it was influenced by the war’s dark and terrifying final months as well as the relief and pride following the Allied victory. It also feels like a kind of sequel to the work that immediately preceded it in Copland’s oeuvre, Appalachian Spring. Both works celebrate the American spirit in different realms – the individual, the family, the community, the army, the nation – and makes clear connections among them.

In using the Fanfare as a unifying theme throughout its four movements, the symphony seems to suggest how the values and commitment it symbolized can be woven into the fabric of our lives. While the theme is only hinted at in the first three movements, it is fully stated and developed in the finale, which could be called Fantasia on Fanfare for the Common Man.

The movement is not all smooth sailing; Copland does not shy away from the tension and struggle of the times, and there is one point about ten minutes into this approximately 14-minute movement that feels apocalyptic. But Copland does not dwell there; if there is one overriding characteristic of the piece through its different moods and episodes it’s its constant motion. Copland seems to be saying that, no matter what happens, Americans keep moving, and keep building toward the future. This is reflected in the work’s Italian tempo marking, Allegro risoluto.

Copland is really the composer who defined what America sounds like, from its open prairies to its folk dances to its violence to its triumphs. His musical vocabulary has influenced film soundtracks and pop music continues to be studied by young composers.

No offense to Tchaikovsky and his pals, but thanks to Copland, we Americans can write the scores to our own celebrations now.

Which brings me to my one other request for July 4 programs: the inclusion of works by composers who reflect our country’s diversity in terms of ethnicity and gender, including some who are still alive! A couple of suggestions that come to mind include a piece that has become a contemporary classic, Danzón No. 2 by the Mexican composer Arturo Márquez, which always brings a crowd to its feet and would be a hit at a July 4 concert; and a piece destined to become a new classic that was written just three years ago by Valerie Coleman: Fanfare for Uncommon Times. Both its title and the music itself indicate that it’s part of a conversation with our past, an acknowledgement of the rocky present, and a reminder that the future is in our hands – which is what any birthday celebration should be about.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.