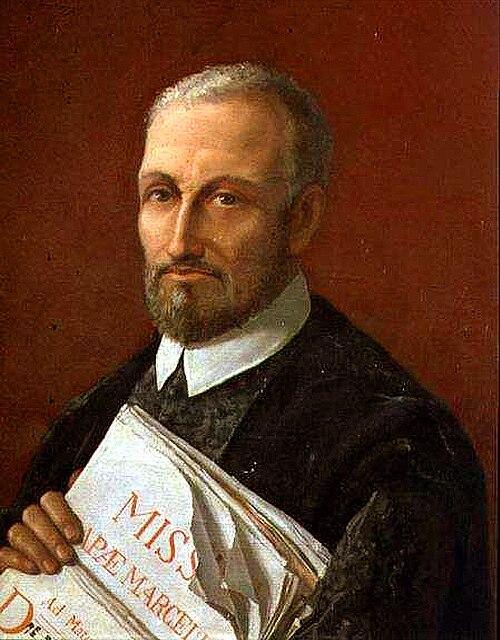

For the last several weeks, I’ve been immersing myself in the world of late-Renaissance vocal music, researching the life and work of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, whose 500th birthday we celebrate this year. Palestrina was a great, prolific, and extremely influential composer who was highly acclaimed during his lifetime, and his reputation only continued to grow for centuries after his death. Throughout my research I’ve been learning many fascinating things about what life and music making was like in 16th-century Rome, but I think my favorite conclusion that my research has led me to is that, among composers whose names we know, Palestrina was the first great Hedgehog composer in classical music. Just in case this comparison of a composer to a small, spiny insectivore seems odd to you, allow me to explain the metaphor.

“A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing.” This quote, attributed to the 7th-century-BC poet Archilochus, was the basis for a fun little classification game coined by the philosopher Isaiah Berlin in his 1953 book “The Hedgehog and the Fox.” Berlin said he meant it to be just a fun little intellectual game, but it really caught on as a way to express real insights in many realms of criticism, from political philosophy to pop culture. These days we might think of it as a precursor to the Harry Potter Sorting Hat, but with only two houses instead of four.

The idea is: you take a famous and accomplished figure in a given field – for example, Shakespeare as a writer – and, by considering their overall range of work, attitudes, and ideas, you decide whether to classify them as a Fox (who revels in versatility and the irreducible complexity of the wide world), or as a Hedgehog (who sees and focuses on one underlying big idea, which they view as the universal lens that harmonizes all of the seeming complexity of the world). I think most people agree that Shakespeare was probably the greatest Fox poet who ever lived. Isaiah Berlin gave the example of Dante as the contrasting great Hedgehog poet of history.

When applying this game to composers, it can be very fun, but also very tricky. A career in music has always required a very wide and versatile range of skills, so it’s hard to find a famous composer whose music doesn’t include plenty of Foxy proclivities. (Orlando di Lasso and Wolfgang Mozart are two of the greatest Fox composers in my book.) On the other hand, especially among the biggest name composers, it’s pretty easy to think of examples of deep and singular creative drives that could be summed up in single phrases, phrases which describe, by the composers’ own lights, just what it was they wrote all their music in the service of. JS Bach’s would be ‘To the glory of God.” Richard Wagner’s would be Gesamtkunstwerk (roughly translates to ‘work encompassing all the arts’). And then, as so often, we’ll eventually come to the impossible question: where do we classify Beethoven? His whole career was one reinvention after another, so his Fox abilities had to be off the charts, but at the same time, almost everything he wrote was so powerfully expressing one thing: music as subjective and unique self-expression. Beethoven contained multitudes, but his music always expressed Beethoven.

For me, the question that determines whether a given composer is a Fox or a Hedgehog, is essentially, where and how does the composer go about looking for the truths that they want their music to express? And the answer to that question goes back to the contrasting visions of the two foundational ancient Greek philosophers: Plate and Aristotle. They are the two central figures depicted in the famous fresco painting by Raphael called The School of Athens. In the painting, Plato is pointing up to the heavens; he says we must look to the home of our eternal souls to find the singular Truth, of which this mortal world’s many and varied things are but imperfect and incomplete copies. Next to him, Aristotle argues, with his open hand stretched forward in front of him, that truth is to be found out there in the world, by experiencing and cataloging the magnificent variety of things and how they interact with each other to create a complex picture that embraces multiple truths, even when they are incommensurate.

I’ve been thinking lately about how Foxes and Hedgehogs fit into the stylistic evolution of classical music throughout its history, and a picture comes to my mind of how new stylistic eras often get started. It goes something like this: a genius Hedgehog composer grows up learning and working in a musical style that doesn’t end up quite fitting their grand vision of what the game of music should be seeking to accomplish. For example, Carl Philip Emanuel Bach with his keyboard music and Christoph Willibald Gluck with his operas. Both started out writing very fine baroque style music, with inherently intricate and ornate musical structures. But they both found that this style just could not communicate effectively the underlying expressive goals that they believed music ought to be striving for. So, these two Hedgehogs felt they had to turn their genius to writing music in a new way, to clarify what they thought was most important for listeners to hear in their music (a more naturalistic human drama in Gluck’s operas, and a dynamic narrative thread of melodic themes in CPE Bach’s instrumental music). They presented their new style so convincingly that the wider culture of classical music started to follow their vision, and thus began a new stylistic era.

This new style then often becomes a great musical playground for young Fox composers (like Haydn and Mozart following on in our Classical Era example) to use their genius to add and assimilate ever greater variety and complexity into the style, and thereby take it to its greatest heights. At that point, the process might begin again, like when a young Hedgehog named Beethoven imbibes the perfected Classical style, but he finds he must do completely new and radical things with it in order to suit his own grand vision of what music should be about.

I don’t want to get carried away here, because I very much doubt that this just-so story of Hedgehogs and Foxes in history is like a natural law; I would never bet money that stylistic change always happens this way in music (or anywhere else, for that matter). But I think it is a fun framework that fits quite a few of the most influential personalities in music history, not least of which is the earliest Hedgehog composer that I know of: our birthday boy, Palestrina.

Early Renaissance music (mainly in the 15th century) was an age of great Fox composers, like Ockeghem, Dufay, and Josquin. By the time the young Palestrina was learning to compose music like them, vocal polyphony of great complexity was the order of the day. Polyphony is the musical texture made from multiple different melodies being sung simultaneously. Sometimes in early Renaissance polyphony, composers were quite happy to throw multiple completely different texts into the mix as well. So, this was music where the words and their emotional meaning were of rather secondary importance to composers.

But for Palestrina’s vision of what music needs to express, the words give you the emotional story, which the music should seek to heighten, intensify, and take right into the spiritual realm. So he perfected his own way of using polyphony, often simplifying and clarifying its texture, so that the words being sung are not only more intelligible to the listener, but their meaning becomes the deep driving force for what’s happening in the music, which, in Palestrina’s hands, starts to sound a lot more like a large-scale dramatic narrative. Palestrina’s new way of using polyphony and counterpoint (which is like the rulebook for how to create and maintain polyphony effectively) proved so compelling that it pretty much took over as the ideal for the late Renaissance, and later great Fox composers like Monteverdi would use it for their own Foxy purposes in the creation of the first masterpieces of opera as the baroque style got underway. (Which perhaps proves that it’s not necessarily always Hedgehogs that start a new style.)

Now, as we wish a very happy birthday to Palestrina, I hope you, dear reader, will have fun deciding and arguing about whether your favorite composers are Hedgehogs or Foxes!

And for a deeper exploration of Palestrina’s life, music, and legacy, please join me for Palestrina 500, a 3-part series airing on January 20 through 22, at 2pm on WETA Virtuoso.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.