The Library of Congress co-commissioned a new work from composer Danny Elfman, and it premieres on May 4 at St. Mark's Episcopal Church by the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. He has composed scores for over 100 films, but this is only his 8th “classical” commission. I spoke to Elfman via Zoom to learn more about this new work, his process, influences, and what is essential for him as an artist.

John Banther: The commission for your new work coming through the Library of Congress premiering with Orpheus, how did this partnership start? Did the LOC give you any direction, any guidelines, or was it really just all up to you?

Danny Elfman: It was just one of those things that came my way. And I was really honored and as often is the case, my classical agent will come up to me or my publisher sometimes with something like this, and I'll just immediately go, " Yeah, sure!"

I was sent an instrumentation list, which was very specific, this many strings, one French horn, one trumpet, one oboe, one clarinet, one bassoon and a piano. And I was like, "Wow, I've never had anything like this. This will be very challenging!"

I've done some quartets. I've really done only big orchestra or very small, like the piano quartet and the percussion quartet. But I haven't classically written anything in between. This was an interesting new thing for me.

JB: Can you tell us a little bit about the work in general, are there any particular themes or subjects, or even a program with it?

DE: This will be my eighth work commission in eight years. I'm trying to do one per year, and hanging onto that goal, but I don't really work around themes. There was a point when I was working with Michael Tilson Thomas on the Cello Concerto I wrote for Gautier Capuçon, where he thought perhaps it should follow this storyline. But as I began writing, I realized, I just don't think that way. Unless it’s a ballet and there’s a story, I just start listening and writing.

In this case, it was very challenging because of course, with a violin or a piano or a cello concerto, you've got a plethora of things to dive into for inspiration. For chamber music, if you're not into pre-20th century music, there's startlingly small amount of stuff to listen to, because I tend to not get very inspired by much before the late 19th-century, let's put it that way, more likely early 20th. But then as we moved into the 20th century, ensembles started to go on the stuff that I grew up on, which was Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Harry Partch, Lou Harrison, very percussion oriented, and then Philip Glass and John Adams.

So I always try to submerge myself in elements to just get my brain soaked up because you have to realize I have very little classical background. I'm just a musical sponge, as it were. I only learned film music by watching films, I have no training in film music. And I grew up loving the music of Stravinsky, Prokofiev, and then later Bartok and Shostakovich, really mostly Russian but not all Russian, early 20th century. And so definitely if I'm writing a violin concerto, I turn to Shostakovich and Prokofiev. And in my case, I also found some inspiration with Leonard Bernstein, and others. And when I did the cello concerto, again, I found myself going back, "How do I get away from Shostakovich...? I can't!” So I listen and ask, " Oh, did Stravinsky write any concertos? Did Bartok write any concertos? Benjamin Britten? Oh, there's a good one.... that kind of thing.

Here I found myself, "wow,” really, when it comes to the early 20th-century, which is always what I'm trying to tap into, which is something that's contemporary but has roots in what I consider to be this golden age of for me, narrative classical music, which is the early to middle 20th century. And it just kept going back to Stravinsky because he was the only one who was doing it for quite a while there. He was just like, " I don't care. There's not much money, it's war time. I'll just write for 12 instruments, I'll write for 14, I'll write for 7."

Because he had this extraordinary ability to just pick any group of instruments and do something amazing for it. And so, I found that it was just literally tripping me up in circles. The problem with Stravinsky is that... Stravinsky is Stravinsky! I don't know how else to put that, but he was able to do orchestrational gymnastics. It's watching the Olympics and going, " Oh, I'm going to try some of these tricks here." or when watching an Olympic athlete, "Well okay, that's a different story, isn't it?"

And that's what Stravinsky will always be for me, that insanely gifted Olympic athlete that is able to do tricks that seem so easy, but he only makes it look or sound easy. I always find myself trying to keep one foot in the 20th, 21st century, and one foot in that period of 1915 to 1935, 40, somewhere in there, because I love narrative writing. That's what inspired me, the idea of... I guess, it's hard to explain. I listened to Mozart and Beethoven, and I always greatly respected Bach, but it never really connected to me until I started hearing these incredible, explosive, melodic pieces that can go any direction at any moment with Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich and the others that I mentioned, Britten and Bartok. As you're listening, you don't know where it's going to go. And I love that but also the idea of thematic variation that didn't follow let's say, eight bar patterns, which is ... Look, I'm the worst music historian in the world, but...

JB: Yes, 8 bar phrases were everything for a while!

DE: For a long time, yeah. You do an 8 or a 16 bar pattern and that will follow with another 8 or 16 bar pattern, which answers the first one. And it makes sense, it's very geometric. And then suddenly with the Rite of Spring and with these Russian composers, anything could happen anywhere.

I could put it best like this, it's what brought me to film music because film music is all inspired by this music, whether it be Horst or Prokofiev or Mahler. I was maybe 10, 15 years, 20 years into my film composing career, when I was driving home listening to a classical music station and I tuned into a piece that I thought must have been film music because it was so visual and so narrative. And I was like, " What movie is this?"

Because the classical station would occasionally play a famous piece of film music, and I remember sitting outside my house, I wouldn't turn the radio off for about 10 minutes because I was waiting for the host to come back and announce "That was... "

And I'm just thinking, "If that's one of my contemporaries, I'm retiring right now!"

And thank God it was a Shostakovich symphony that I had never heard before, and I felt I was given a lease to continue. But it sounded so cinematic to me that I was almost visualizing what type of scene or action this might have been happening for. It was only a few minutes of something. It was the last few minutes but there was something about the explosive narrative shift that happened in the 20th century that caught my attention. And then as I got into film music in the late 19th to 20th century to be fair, it just made sense for me because ... For example, I remember writing a score and somebody had asked me, " Oh, do you listen to Wagner?" I said, " No, but I listen to a lot of friends, Waxman and Korngold, who listen to a lot of Wagner."

It all gets combined together in a wonderful way that really pulled me in. When I started doing these classical commissions, it was my goal because I'd already been doing film music on stage now for 12 years. And we're pulling really good audiences and they were loving this stuff, and I kept thinking, "There must be a way to write classical music that would appeal both to a classical music listener, but also to somebody who listens to this film music, that would be recognizable."

You don't want to use the word alienating... but a lot of 20th century music... It gets very…

JB: Contemporary music can ask a lot from listeners sometimes.

DE: It asks a lot of the listener. In other words, well, this was really interesting... when my son was four years old I put on a DVD of Michael Tilson Thomas with the San Francisco Symphony doing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and he asked to hear it every day for a month. It was interesting to me how this music can connect with a four-year-old. It has that ability. Now, obviously you're not going to play contemporary music from the second half of the 20th century and expect to hold a kid's attention in most cases.

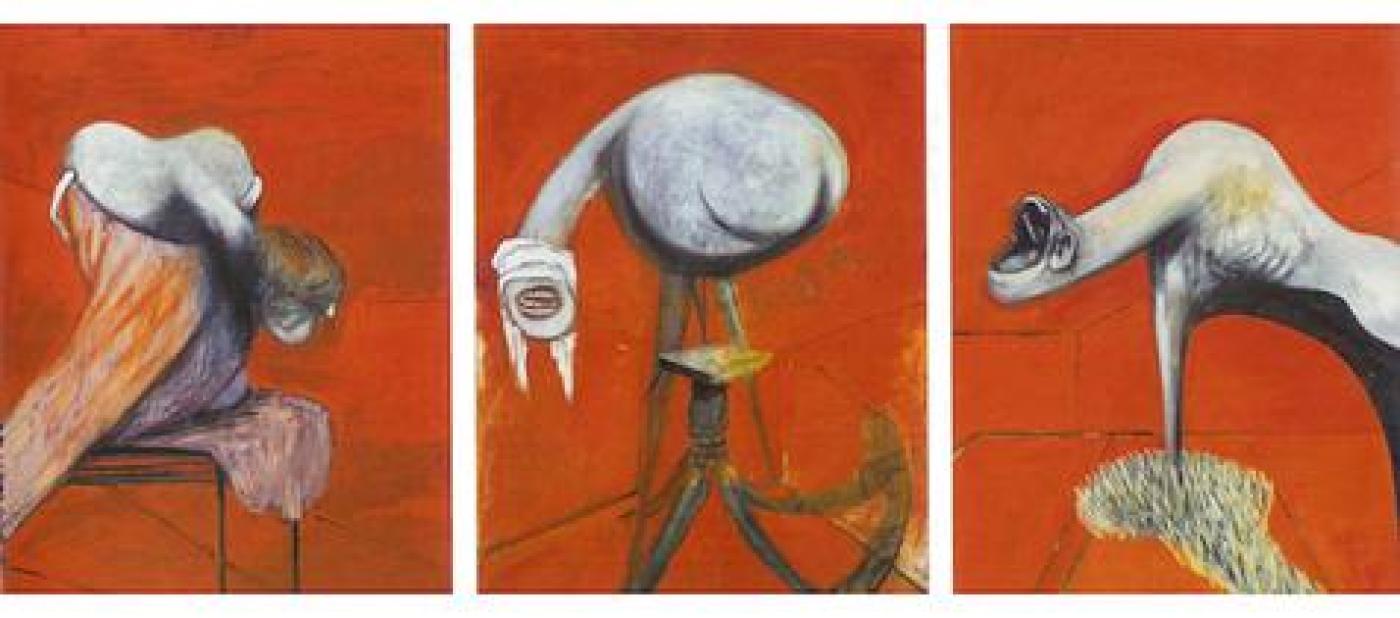

It's like certain types of contemporary art. If you don't understand what the artist is doing, you look at it and you either say, " I don't get it, it's just squares."

Or whatever. As opposed to looking at a painting by Francis Bacon that you just look at it and you just go, " Wow! What is that? It is intense."

Anybody seeing it is going to see something really intense, and they don't have to understand it. They may like it, they may not like it, but they're definitely going to get this strong, visceral reaction. It's very powerful. And so it's just a template that I've kept in my head of wanting to try to do this thing that I feel not many contemporary composers are doing, of working both within the context of melody and variation of melody, but also working in modern context format.

JB: Yeah. It sounds like for you, it's an advantage, approaching this music coming from so much work in film. Like you said when you're talking about Harrison and Bartok, that actually really resonates for me with your music and the ability to go anywhere at any moment.

DE: As classical music burst into the 20th century, there is this freedom of, its really just storytelling. You come up with a story in your own head but there's definitely some wild story here.

But this was a very long, elaborate way of saying no, I don't start with a single piece of imagery that inspires it, or a poem or a story. I really just dive in and listen and then I just let my fingers start. And my normal process for something like this would be I'm going to start with maybe 12 or 14 ideas, improvisations, and then I'm going to start to elaborate on them. And then a couple of them will go from a little 30 second idea to suddenly six of them are now a minute, minute and a half, two minutes long. And I go, " That's interesting, six or eight."

And then at a certain point, some of them are just starting to take off on their own and some just aren't. And before I know it, four pieces are developing themselves and there's a symmetry to it that's appealing to me. I do follow this I suppose, an archaic sensibility of it's still a show, and I want to start and end big.

And it's funny, I'm obsessive about symmetry. And when I heard Shostakovich's first violin concerto, the symmetry of it made perfect sense. The first and the fourth movement are really the most classical and melodic in a very specific way that to me, and I'm just saying this is my subjective listen, is that they reflect each other. They're tied a little more to a recognizable form and gestures. And then the second and third movement go off in two completely different directions, one of them being as heavy and deep as anything only a Russian who lived under Stalin for many years can really tap into, and the other one almost crazy, almost cartoonish at moments in a way. But the symmetry of that was perfect for me, that the first and last movement should somehow reflect themselves in a certain stylistic way, where one closes off where the other one might begin in a certain sense. Then in between, whether it's one or two movements, (I frequently find myself with four) can just go now to the left and to the right, anywhere. Now there's no rules and there is the symmetry. And that's how I constructed my violin concerto, my cello concerto. I really tried with the percussion concerto to get away. I said, "I'm going to have three or five movements here." And it ended up being four. It just was like, "Ugh, it still happened to me!"

And so I do find myself starting with these ideas, and then out of them I see one of them finds itself, " I like that as an opening..." and one of them ends up with, "I think that'll close it off nicely..." and then something completely different will say, "Tuck me in the middle. I'll be fine here."

JB: Can expect some symmetry with this new premiere?

DE: Maybe, because I'm honestly trying to get out of it, but my brain just keeps pulling me back. You may listen to it and you go, "Oh, not so much this time." Or "Danny, I think you pulled it off. You broke your symmetry." Or you may go, " Yeah, I hear it. I hear just what you were talking about."

In which case I don't consider it a failure because obviously if I was intent on not doing that, I would not do it, but I tend to follow the music and I let it work itself out.

When I start a piece, it's always a lot of effort and a lot of work, especially finding a thematic sense and tone. But then I hope in a film score where I'm scoring and suddenly it takes off and I'm following, I don't know where it's going to go next, and I'm surprised occasionally, like, " Wow, I wasn't expecting that."

And those are my favorite moments of scoring, where I'm surprised by what happens musically because I don't block out the whole scene. I only block out the idea, the concept, the tone, the theme, and then I'll start it, but then I'm hoping it starts taking me along. And with the classical works, that's always the case. I really think it's like pushing a train uphill in the beginning, it's like this huge effort to get it going. And then there's a point where it's coasting and it's like, " Oh, I'm enjoying this now. I've got some momentum."

And then if I'm lucky, there'll be some moments where, " Oh wow, it's picking up speed and I don't know what's going to happen."

And there's a turn ahead and I wonder if I'm going to derail. And that's the most fun, when it's like, " This is going someplace crazy. I don't know what's going on here but it's interesting and I'll just stay with it and see what happens."

And occasionally, it leads to a disaster train wreck and I've got to go rebuild the train and start again. But that's the fun of music, it's getting into train wrecks and knowing that you'll walk out of it.

JB: That reminds me, when you did Coachella last year combining decades old material with new and your film music. You said leading up to it, "Oh God, this is the worst idea of my life.”

Thankfully it wasn't in the end, but it seems like so many great or at least fun or rewarding projects, start with some, " Oh God, what have I done?"

DE: Oh, believe me, so much of my life has been that. And definitely doing this crazy show of combining old music, new music and film music all together in a mishmash seemed like a concept when I pitched it a year earlier to the promoter, but when I was actually getting ready to do it I thought I would get killed. I felt like I was going to walk out to a firing squad, that I was going to have... I have no idea how many people are out there. It's dark, you can't see. It's like, " Was it 10,000 or 20,000?"

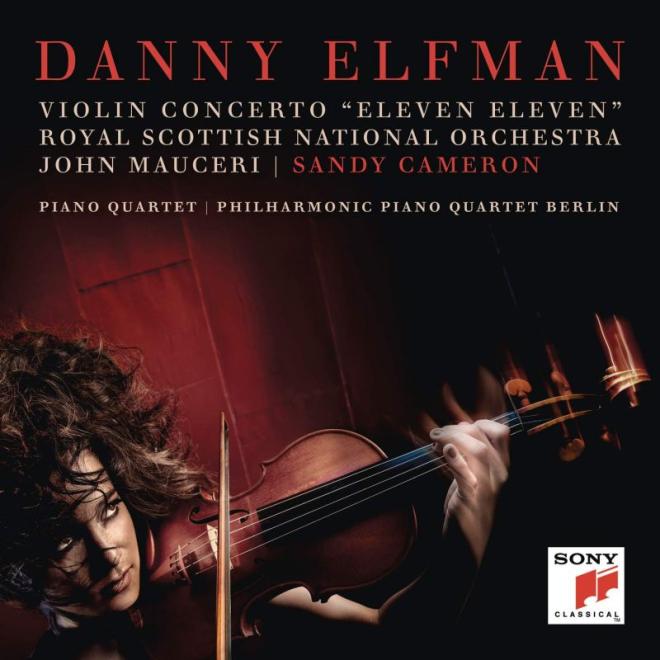

Or whatever it was. And they're just going to walk away and there'd be six people left by the time I got to the last song. And it felt that way when I did my violin concerto as well. I felt like, "Oh, my God. I don't know what this is. We're going to Prague. The audience has no idea what they're going to hear, they only know my film music. This is going to be a disaster."

And I made no attempt to make the concerto sound like film music. That was the whole point. It's an argument I've gotten into frequently with my conductor that I frequently work with, John Mauceri. John will argue that film music is the classical music of today, and I'll argue it's not. In fact, I couldn't disagree more. Film music 90% of the time has to get greatly simplified and condensed in order to work with a scene, not fight it, and to go with the movie. Occasionally, you're allowed to do a score that gets really dense and wild and crazy, but those are so far and few in between. Generally speaking, they have to be lean and simple and doing a specific thing. And I said, "It's not classical music because people who go to hear music in a concert hall of film music want to hear the music that plays to the movie that they love."

They're picturing the movie, whether it be Star Wars or whether it be Edward Scissorhands or whether it be whatever, Lord of the Rings, they're not just going to hear a piece of music, they're going to hear the music to the movie that they love. And the goal with starting with concert music was, "Can I put music out there that has no association with anything? It just has to stand up on its own."

The stakes are so much higher. When people love a movie, they tend to love the music, hence you've got concerts with some of the most boring and some of the best music written in the last 50 years. Sometimes it's like, "Oh, my God. This music's so great to hear it played on its own because it's such a wonderful score."

And sometimes it's like, " God, this music is so boring but the movie was great."

It's like, "Okay, I'll just go with it. Reminds me of the movie but the music on its own, not a chance, not in a million years."

And so this is just a debate that we've had running for ages. And I still believe that music to stand on its own, should be standing on its own without the picture. Because even people that go and hear Bernard Hermann's music, and every time I hear it live it's so wonderful, but they tend to relate it to the movie. And there just aren't many scores that one would hear. They have no idea what the score is from, " But I don't care, I'm just listening to this music and I love it." It tends to not be the case. Yeah.

JB: I think it was a long time ago in an interview you mentioned when you heard your music played for the first time by a full orchestra, it was one of the most thrilling experiences of your life. Decades later, do you still feel that same thrill when you hear a work premiered like this one coming up?

DE: Well, yeah. Definitely when I hear a concert work, there's a lot more attention and anxiety of what's it going to be? For a film piece after a hundred scores, I know pretty well as I'm writing it exactly what it's going to sound like. It's still a thrill to hear a real orchestra always play back music that I've been writing on synthetic samples, it's a relief is what it is. It takes on all this depth and color that samples just don't have. But for the classical stuff, because it is liberating and I'm allowed to get far more dense and experiment with stuff without having a director look at me going, " Danny, what the heck is that?"

I do get out there in these areas that are fun for me but it also gives me much less of a sense of, "I don't know what this is going to sound like."

35 years of hearing all these scores played back, that's not helping me in this piece, this is a whole other animal. And so I do get that sense every time I have a concert piece of like, "Oh, my God. Here it goes. Is it going to work? Is it going to be a disaster?"

Really, that's the beauty of it. It's like theater, in the sense that you're opening a play, you don't know how it's going to work. You don't know how the actors are going to treat it, meaning here the orchestra. You don't know how the audience is going to respond. There are no assurances at all. You're not in a blockbuster film where you could look at it and you go, "Look, people are going to love this film. I hope they notice the music, but they're going to love this film.” It's definitely still a nail-biting experience.

JB: Probably great relief when that last note is played and there's applause.

DE: Oh, my God. Yeah, yeah. I'm just wrapped up tight in the ball, and I'm hearing every little imperfection and I'm hearing like, "Oh God, that phrase, I'm going to have to fix that."

I'm making notes in my mind, "Oh, I'm going to have to fix that."

There's always going to be revisions after the first performance on anything. And so I'll hear a couple of things go down and say "Oh God, it worked so well in my head. But I'm going to have to simplify that, this line is fighting that line, and this instrument's getting lost. And I'm going to have to make some adjustments."

But still, by and large, I'll be making a lot of little notes for myself. I'm hoping that the whole piece still has energy and life and plays and works, but I don't know until I get there. And so it definitely keeps me out of my comfort zone, which is the whole idea. These concert works, Coachella and that stuff, it's just things to push me way out of my film music comfort zone where inevitably, after 37 years or whatever it's been, you start to fall into patterns of like, "I get this. I know what this is, and they know what to expect from me."

And that's fine, it's good. You're a craftsman and you've developed a craft. But I think it's essential for myself at least, as an artist, to get out of that comfort zone into the nail-biting area of like, " Oh, my God. This could be a disaster." I need that.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.