A Washington Post review of a 2015 concert by the Shanghai Quartet at the Freer Gallery began "If there’s a documentary film crew following your every move, you must be doing something interesting.” Eight years later, on the occasion of the fortieth anniversary of the group's founding, we can finally see the footage captured by that crew in the documentary Behind the Strings, which played the film festival circuit in 2020 to great acclaim and is coming to WETA PBS and WETA World this month.

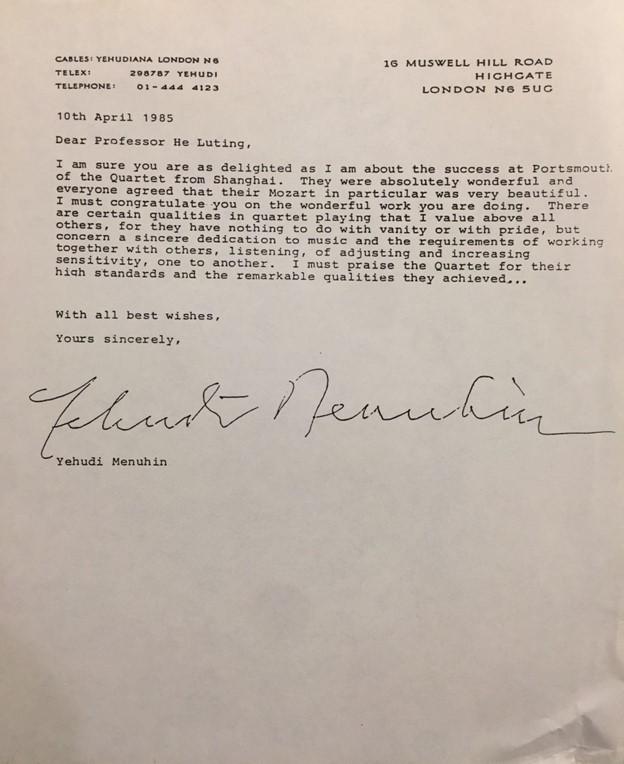

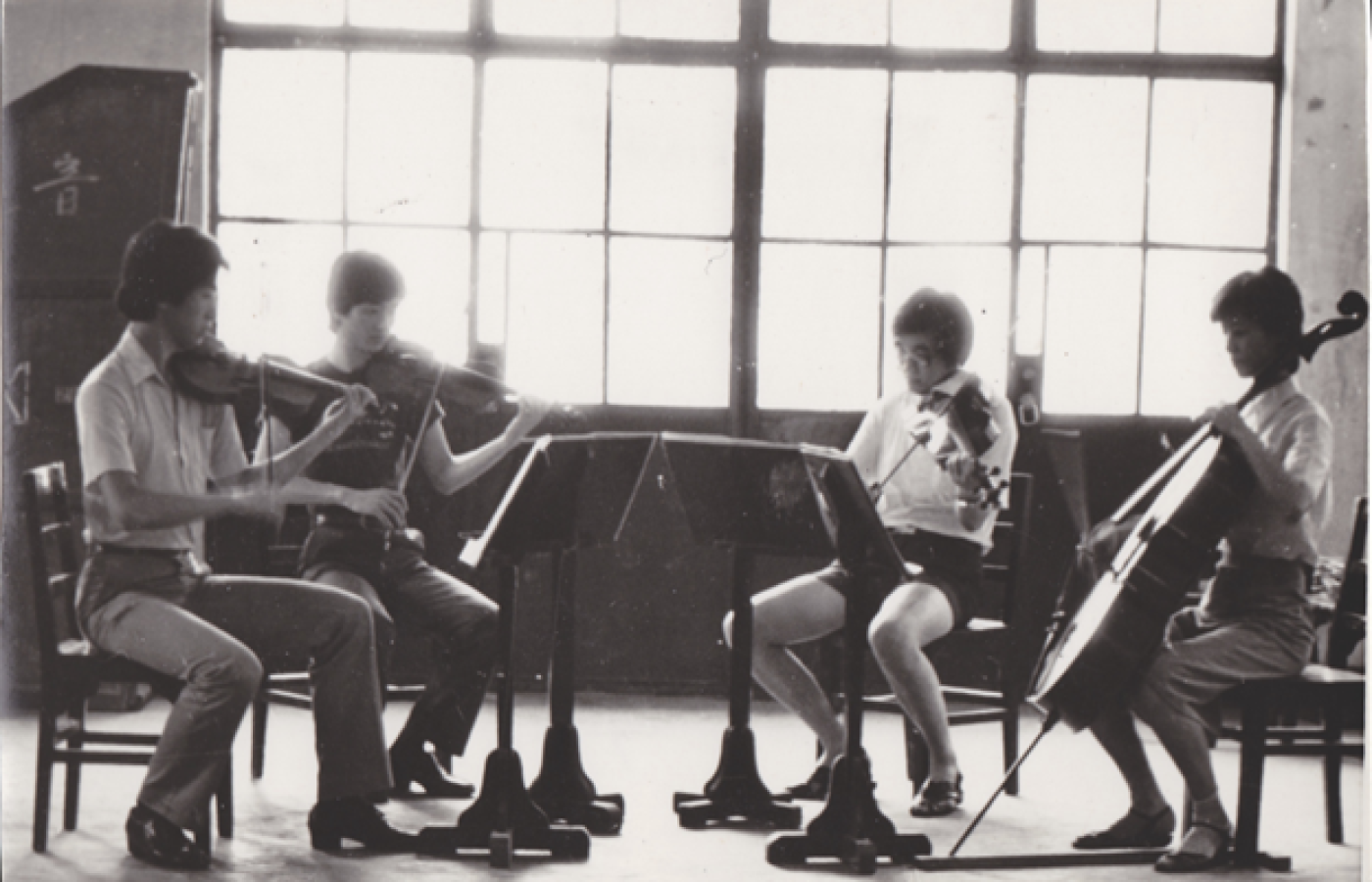

It is indeed an interesting story. Two brothers, Weigang and Honggang Li, were born in Shanghai in the 1960s and given no choice but to play the violin by their parents who were themselves professional violinists. Their formative years occurred in the shadow of the Cultural Revolution; there was a harrowing period in which all Western music was banned and their family was under surveillance. With the death of Mao in 1976 there began a gradual easing of restrictions. which led to Weigang's first appearance in a PBS documentary: in 1979, at age 15, he participated in a master class with Isaac Stern which can be seen in the Academy Award-winning film From Mao to Mozart. They attended the Shanghai Conservatory of Music where they formed the Shanghai Quartet with two classmates in 1983. The following year they won second prize at a prestigious competition in England, a performance that inspired its jury president Yehudi Menuhin to write the letter you see above and jury member Shmuel Ashkenazi to take them under his wing and invite them to the United States, where they have been based ever since. In recent years they have re-established a relationship with their home country and since 2020 have been resident faculty members at the branch of The Juilliard School in Tianjin.

The brothers have been the constant element in the ensemble that has seen several personnel changes, as well as one instrument change, when Honggang switched from violin to viola in 1990. At that time their childhood friend Yi-Wen Jiang joined the group as second violinist, and it is he who is seen in that role in the documentary. In 2020 he was replaced by Angelo Xiang Yu. American cellist Nicholas Tzavaras joined the quartet in 2000; he has also been seen in an Academy Award-nominated documentary aired on PBS, the 1995 film Small Wonders, about his mother, the renowned violin pedagogue Roberta Guaspari.

I submitted a few questions for the group to answer for this article, and am pleased and honored to present their responses, which have been lightly edited.

James Jacobs: When you come back to the US for your tour next spring you'll be playing works by Haydn, Dvorak and Grieg that you've doubtless played many times in the past 40 years. When you start preparing for this tour, where will you start?

Weigang Li: Each time we revisit a piece of music that we have played many times for many years but was put away for some time, we would spend time individually and collectively looking at the piece as if it’s new and fresh to us.

This is not so easy to do because just like old habits, all of us are likely to stay with us. We sometimes listen to a recording of our previous performance and realize things that we would like to do differently or simply to improve or correct. When all quartet members are trying to do it together, it is quite wonderful to be able to make the next performance even more convincing and very fresh.

JJ: The choice of the Dvorak is consistent with the group's interest in works inspired by folk music, such as the work by Zhou Long based on Chinese songs currently in your repertoire. Do you consciously adapt a different style when playing these works? Do you find that there is some affinity among the folk materials of vastly different cultures? Have you listened to folk musicians who have inspired how you play?

Weigang Li: Music is such a magical art form that it will lead you to play it in the right flavor and style. Of course, knowledge, experience and even research will greatly help one’s understanding and learn to master each folk music’s particular style and tonality. So much music in almost every composer has folk elements and it would be very dull if they are played without the understanding of where it comes from. You must make all music come alive.

JJ: Is there a composer, period, or type of repertoire you still haven't explored that could be part of the projects still ahead for you?

Weigang Li: For the past 40 years, we have performed hundreds of pieces of music of all genres from Bach to music written yesterday and of many nationalities. The repertoire of our string quartet is so vast and there are still quite a few great classics I would love to learn and play including some more wonderful Haydn quartets or Alban Berg. We are also constantly looking for good new music to play and will continue to commission works from young composers.

JJ: I'm sure many things have changed over the course of the last forty years, but what hasn't changed?

Weigang Li: We always put music and composer’s intentions in front of ourselves.

Honggang Li We are still very serious and passionate about the music we’re playing.

Nick Tzavaras: Our industry has changed drastically since 1983 (and 2000 when I joined the Shanghai Quartet) but we still begin and end our journey as performers by saying to ourselves, “how can we serve the composer and give a performance that truly resonates with our audiences”.

I always want new and experienced audience members to come away from our concerts inspired to listen to more classical music. Of course, we cannot evoke the exact emotions or precise feelings of the composer, but we certainly can try to inspire ideas in our audiences that somehow loosely correlate to what we are trying to say on stage. We still strive for a very high level of technical perfection to better serve each piece that we perform. However, as we have matured over the years, our ability to give a profound and moving performance, especially through works that we have visited many times over the years, is certainly much easier.

We now have a strong understanding of how to work, how to be efficient with our preparation and, perhaps most importantly, have been afforded the stage time to reflect on and continue to improve upon our interpretation and performance.

If we were ever given the miraculous opportunity to perform for Beethoven himself, for example, we hope he would be satisfied with our reading of his work and perhaps notice some aspects of our interpretation that he liked which were unique to our ensemble.

JJ: Do you find that there's been a change in the concert experience? Are audiences different now than they were forty years ago? Or even ten years ago? What is the kind of performance space and context do you feel most comfortable performing in?

Weigang Li: Even 35 years ago when we started to play many concerts in the US, people were saying string quartet music audiences are aging and will not sustain when these audiences are gone. But we gradually also realized that people get older and they tend to switch from listening to symphony music to more chamber music. In quite a number of cities in China, there have been tremendous growth in young people going to classical music concerts. We played 4 different string quartet programs within 5 days in Guangzhou recently. Half of the young audience came to all 4 concerts. That was quite shocking and telling, I think.

Honggang Li: Of course, the biggest change is in China. But every city is different. Last night we played in Shanghai Symphony Hall. The audience is as good as the best in Europe or the U.S. Our favorite place is always in a smaller space because of its intimacy.

JJ: Do you find that there's been a change in your teaching experience? Do you find that something fundamental has or hasn't changed in the attitudes of the student musicians you work with?

Weigang Li: Fundamental in teaching in terms of how to play music has not changed too much during the past, except the playing style of Baroque music has gone through a major transformation since my student days. For me, some are for the good and others are just a phase one had to go through. I think the biggest change or difference in the music industry is the internet and digital age which is greatly influencing the next generations of musicians. The young generation of musicians must learn how to adapt themselves to the new technology and new ways of getting their music out and to the audiences. Without that it’s almost impossible for them to survive.

Nick Tzavaras: I do believe there is a direct correlation between performance and teaching. I’ve found that the more I teach, the more I try to enunciate how I do something on the cello or in a string quartet, the better performer I become.

Some say: do as I say not as I do. I really do try to teach exactly how I play, using my experience both as a performer and as an educator, to improve my teaching. This means trying to explain to a student something that may be a very natural aspect of my playing that I take for granted.

As an aside, I also believe we should be able to explain our teaching using multiple avenues of expression. In other words, teaching is not one dimensional and often we must figure out many different explanations to get a student to understand something that might be quite foreign to them. Something that one student may get instantly, may not be as straightforward for another. This continuously challenges educators to rephrase, re-think, re-interpret how or why we turn a phrase in a particular way. This exploration and evaluation of my own performances has certainly improved my teaching in a profound and revelatory manner.

JJ: What advice would you give to a string quartet that just formed at a conservatory and is determined to turn professional? For that matter, what advice would you give yourselves if you could go back in time to 1983?

Weigang Li: The hardest thing for string quartet, besides dozens of difficult aspects, is staying together! My advice to a young string quartet is to find good coaches, work very hard, don’t take each other’s criticism personally and learn to compromise.

In our early days, we didn’t have many shortcuts and “wasted” a lot of time. But thinking back now, actually those wasted times were also valuable, especially when I started to teach. I know pretty well how to let my students avoid too much wasted time.

Honggang Li: Keep your mind open. Imagination is very important, musically and career path too.

Nick Tzavaras: I am fortunate to frequently have opportunities to advise young string quartets on how to launch or sustain a career in classical music, and I often find myself spending a good deal of effort explaining how the market has changed. Groups can no longer rely only on rehearsing and practicing for hours on end. There has become a shift in our industry that is encouraging performers to begin to cultivate a theme for a concert. Simply put, performers need to give much more thought to curating their repertoire in a performance, creating a thread that ties an entire program together.

Further, our industry is investing much more in the music that is composed today. This is absolutely wonderful. Having a well-balanced program that has a theme and has a work or two that is just a few years or decades old is a very good thing for our business!

I am also encouraging groups to take more business classes. I think we musicians often don’t realize that a string quartet is like being a small business owner. We need to be much more cognizant of branding, marketing, and the economics of owning a business. Playing well and being devoted to the craft is just the start, so to speak, or the entry point for a young ensemble. Sustaining in this business requires much savvier, much more long-term vision, and taking some business classes certainly can’t hurt a young string quartet as they need to always differentiate themselves from their peers.

JJ: Watching the documentary creates some concern for your work-life balance! It shows the struggles of raising a family while maintaining an international career. We need an update, since the kids we see in the film are now teens! Do they ever travel with you? Have things gotten easier or harder in that regard?

Weigang Li: I think it is very hard on our spouses when the kids were very young. My child is 17 now and it’s much easier to manage. Spending 180 days on the road and maintaining a full teaching schedule is also very challenging. It leaves very little time to be with family.

Nick Tzavaras: Families are always the biggest challenge in every respect for musicians in a professional string quartet. And, though my family is now not nearly as young as when the documentary was shot, things are still no less challenging. It’s a work in progress that we need to always remember to thank our partners who, in the background and often without a complaint, allow us to continue to be artists and, at times, be absent from some (or many) of the daily family activities.

I think I can speak for all players in string quartets when I say if it wasn’t for their partners holding down the fort at home, we would all have to hang up our instruments and call it quits. So, for every successful quartet there are partners behind the scenes who are the true heroes and really deserve to be recognized as the only reason a quartet can find success, even after 40 years on the road.

Behind the Strings premieres on Monday, October 16, at 8 pm on WETA World. Click here for a full schedule of broadcast times.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.