The first of Amy Beach’s three settings of Shakespearean texts for women’s chorus is based on this speech for the hard-working First Fairy from Act 2, scene one of A Midsummer Night's Dream. In her setting in four parts it sounds like all of Titania’s retinue is simultaneously anxious about their workload while also taking pride in their work:

Over hill, over dale,

Thorough bush, thorough brier,

Over park, over pale,

Thorough flood, thorough fire;

I do wander everywhere,

Swifter than the moon's sphere.

And I serve the Fairy Queen,

To dew her orbs upon the green.

The cowslips tall her pensioners be;

In their gold coats spots you see;

Those be rubies, fairy favors;

In those freckles live their savors.

I must go seek some dewdrops here

And hang a pearl in every cowslip’s ear.

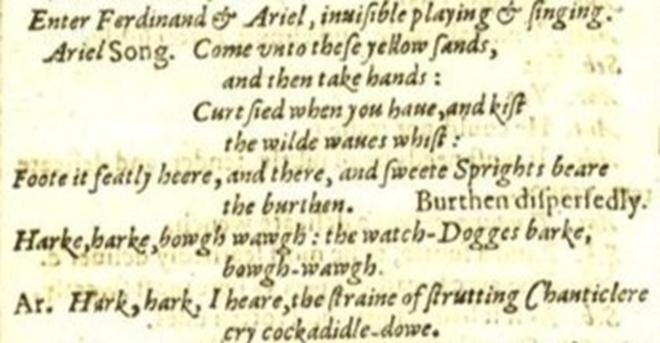

The second chorus is a setting of the song Ariel sings in Act 1, scene two of The Tempest, leading Ferdinand, one of the men shipwrecked on Prospero’s island, away from the others and toward his fateful meeting with Prospero’s daughter Miranda.

Come unto these yellow sands,

And then take hands.

Curtsied when you have, and kissed

The wild waves whist.

Foot it featly here and there,

And sweet sprites the burden bear.

This is the text as Beach set it; she rearranged the last three words to create a cleaner rhyme. She then adds tra-la-la, a substitute for the imitations of watchdogs and chanticleers in the original text.

For the third chorus Beach returns to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, this time from the play’s final pages, when the magically reconciled Oberon and Titania lead the fairies in a song and dance as their gift of enchantment to the newlyweds Theseus and Hippolyta.

OBERON

Through the house give glimmering light,

By the dead and drowsy fire.

Every elf and fairy sprite,

Hop as light as bird from brier,

And this ditty after me,

Sing and dance it trippingly.

TITANIA

First rehearse your song by rote,

To each word a warbling note.

Hand in hand, with fairy grace,

Will we sing and bless this place.

Beach infuses these settings, composed in 1897 with a lightness of sprit that both looks backwards to Mendelssohn and, with a few sly harmonies and textures, forward to 20th century popular music. (Am I the only one who hears a foreshadowing of the Andrews Sisters?)

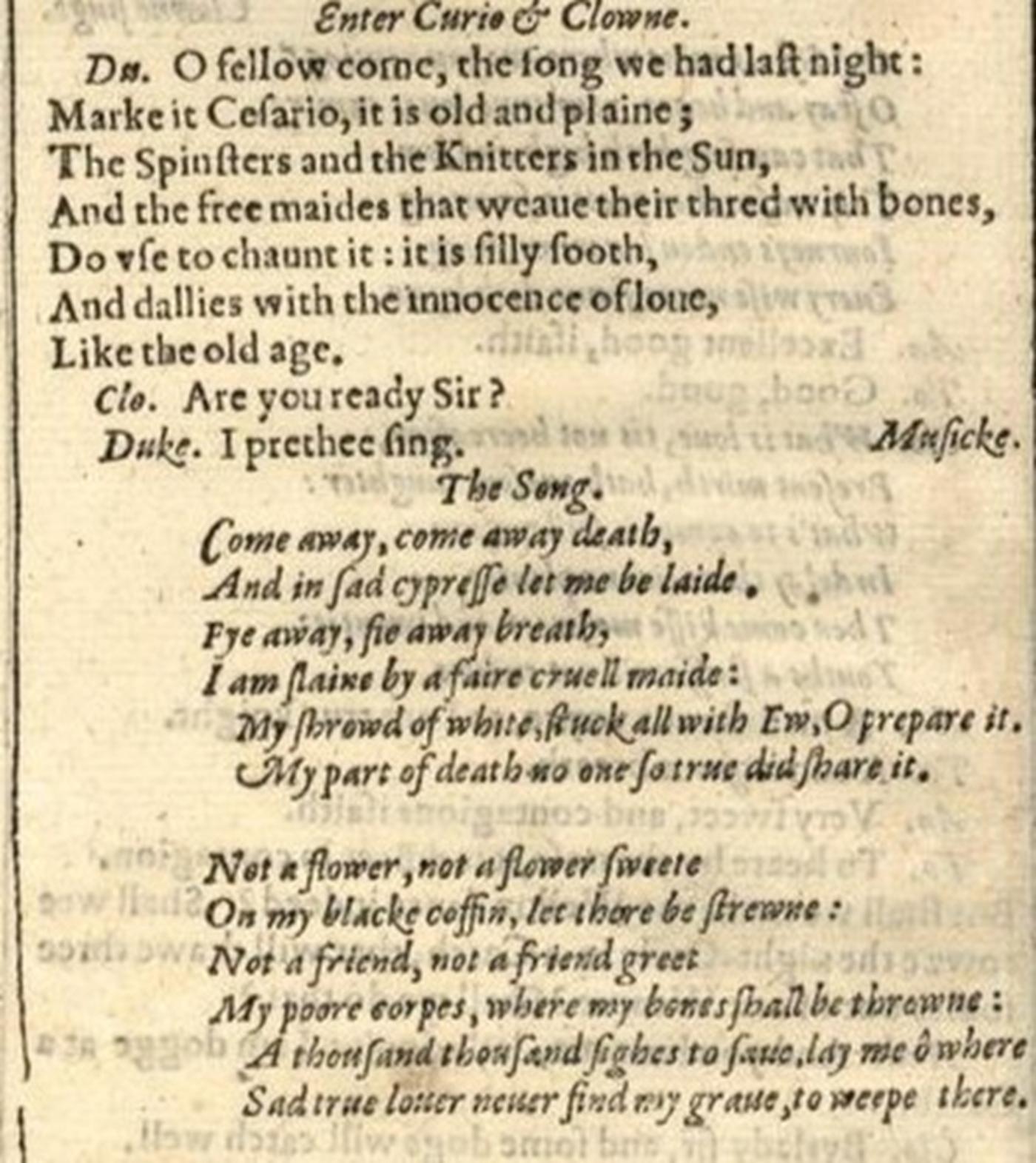

We then turn to Johannes Brahms and his setting, also for women’s chorus here accompanied by two horns and harp, of “Come Away, Death” (in German) from Act 2, scene 4 of Twelfth Night, when it is sung by Feste under orders from Duke Orsino, who introduces it thus:

O, fellow, come, the song we had last night.—

Mark it, Cesario. It is old and plain;

The spinsters and the knitters in the sun

And the free maids that weave their thread withbones

Do use to chant it. It is silly sooth,

And dallies with the innocence of love

Like the old age.

Shakespeare is obviously trying to make the Duke look ridiculous, because the song is nothing like what he is describing:

Come away, come away, death,

And in sad cypress let me be laid.

Fly away, fly away, breath,

I am slain by a fair cruel maid.

My shroud of white, stuck all with yew,

O, prepare it!

My part of death, no one so true

Did share it.

Not a flower, not a flower sweet

On my black coffin let there be strown;

Not a friend, not a friend greet

My poor corpse where my bones shall be thrown.

A thousand thousand sighs to save,

Lay me, O, where

Sad true lover never find my grave

To weep there.

This is such an extreme version of the kind of melancholy, death-obsessed love songs made popular at the time by the likes of John Dowland and Thomas Campion that one wonders if Shakespeare is making fun of them too. In any case Brahms doesn’t take the bait; his setting has no trace of self-pity and instead takes its cue from the image in the first line of summoning death, with the horns deployed to sound like they’re at the hunt; it feels like the singer has already gone over to the other side (cue the harp) and is explaining his situation to his mourners while assuming angelic form. The song has a lyrical resolve that makes its text seem even more unsettling.

Tonight’s set ends with Franz Liszt’s transcription for solo piano of Franz Schubert’s setting of this song from Cymbeline:

Hark, hark, the lark at heaven’s gate sings,

And Phoebus gins arise,

His steeds to water at those springs

On chaliced flowers that lies;

And winking Mary-buds begin

To ope their golden eyes.

With everything that pretty is,

My lady sweet, arise,

Arise, arise.

In the play the song is sung by the arrogant, crude Cloten, the son of the queen, as a sunrise serenade for his (unrelated by blood) stepsister Imogen, who is definitely not interested. There is no indication in the text that this is supposed to sound bad, so presumably Cloten is a competent singer but there’s nothing special about either his voice or this song. Schubert provides a melody that is lovely and pleasant but nothing that that would melt the heart of someone has serious as Imogen; it sounds like the singer could break into a yodel at any second. Liszt’s transcription maintains the charm; this might be the one Shakespeare song that is nicer to hear out of context of the original play.

The Life and Music of Amy Beach

The Life and Music of Johannes Brahms

The Life and Music of Franz Schubert

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.