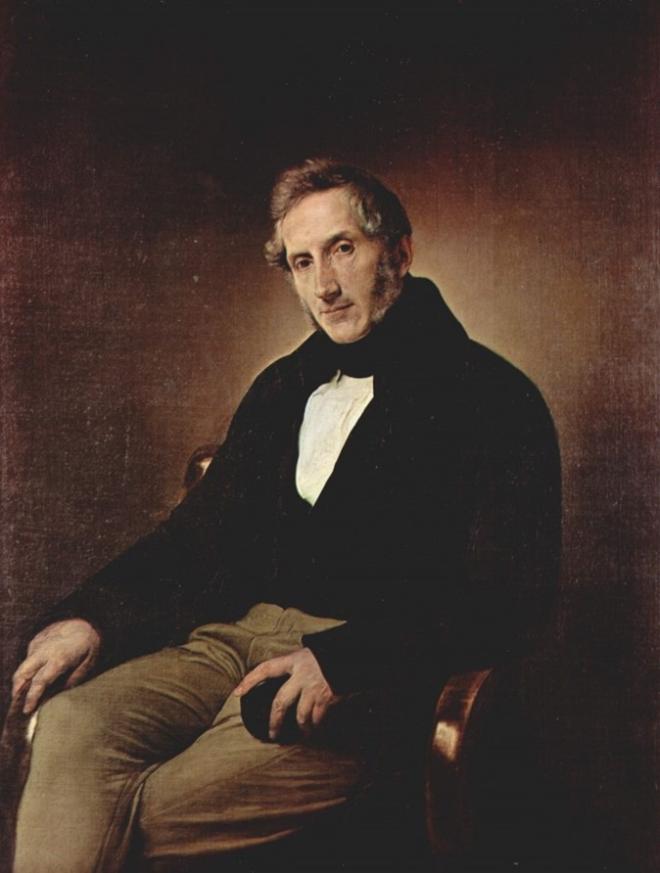

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the first performance of the Requiem Mass by Giuseppe Verdi. The premiere took place under the direction of the composer at St. Mark's Church in Milan on Friday, May 22, 1874, one year to the day after the death of Alessandro Manzoni, to whose memory the work is dedicated. Manzoni was a celebrated writer of novels, poetry and philosophy who late in life also entered the political arena, and he shared with Verdi a vision for a united Italy, a movement called the Risorgimento. Verdi greatly admired Manzoni, and when he died, he wrote "Now all is over! And with him ends the purest, the holiest, the greatest of our glories."

His decision to honor Manzoni with a full-length Requiem mass was inspired by an abandoned project from five years earlier, when Verdi tried to organize an effort to compile a requiem to commemorate the death of Gioacchino Rossini in 1868, to have been written collectively by the major Italian composers of the day. Verdi wrote the Libera Me for that unrealized work, which he repurposed for the Manzoni requiem. In a sense there was a common theme in both projects, for both Rossini and Manzoni represented the idea of a pan-Italian culture when that was something of a radical notion, because for centuries what we now think of as Italy was a collection of disparate regional cultures related only by proximity and language.

Therefore, it’s hard to escape the notion that this piece is a political and social statement as well as an expression of personal grief – unsurprising from the composer of Don Carlos, Nabucco, and several other operas in which Verdi explores the tension between the public and private sphere. His opinions about political power and social justice were much more fervent and well defined than his religious beliefs; as a result, the Requiem seems less concerned with the afterlife than with the earthly plane of the living. He seems less interested in comforting mourners than in providing a primal catharsis that acknowledges their sorrow while also rousing them from the paralysis of grief. He seems to be saying that the best way to remember the death of great men is to get to work to realize their dreams of a just and unified society.

Perhaps this is why the piece feels more like a highly charged drama than an opportunity for spiritual contemplation. It has sometimes been called "the greatest Italian opera ever written", though it needs no sets, costumes or specific plot to convey its power and emotional impact (though there have been several experimental stagings of the work incorporating theatrical elements). It has gained tremendous popularity as a concert work while also frequently used for commemorative purposes. In the last three years it has been performed to memorialize the victims of Covid, the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, and the casualties of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In the years 1943-44 it was performed sixteen times by prisoners in the Terezin concentration camp, where, under the guise of its being used to demonstrate that the camp was a hive of cultural activity, it served as a subversive and cathartic expression of defiance before the majority of those performers were shipped off to their deaths. (There’s an excellent series of concerts and a documentary about this called Defiant Requiem.)

I have to admit that I was slow to appreciate this work. My first encounter with it was when I walked into a rehearsal of it in which several friends of mine were playing in the orchestra. They began with the Dies Irae section and it deeply upset me. This was early December 1978, a dark time in the Bay Area where I grew up; within the last two weeks of November was the mass suicide in Guyana that included the parents of a couple of my classmates, as well as the assassinations of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. The violence of the music seemed to my teenage self an obscene way to commemorate the dead; I interpreted the terrifying judgement calls of the score’s eight trumpets as an indication that Verdi was somehow sanctifying a justification for brutality and bloodshed, implying that there was some righteousness in the slaughter and punishment the cosmos inflicted on us. It was the last thing I wanted to hear at that time; the music felt like part of the problem instead of a way to help us cope with it.

But as I grew up and continued to confront the piece I began to understand that the music was not expressing or condoning violence, but anger about the violence. It was an expression of collective outrage about humanity’s capacity for violence.

It's hard to think of another work that is such an eloquent expression of anger - not the anger that paralyzes us or brings us down to the level of our oppressors, but the anger that ennobles and motivates us to rage against the forces that take the people we love away from us.

Indeed, this piece not only gives voice to our anger, but to all the stages of grief. As I can attest, it’s not music for kids. It’s for those who have not only stared into the abyss of death, but into the darkest recesses of human behavior. Unlike the other masterpiece that celebrated a milestone this month, Beethoven’s Ninth, Verdi’s Requiem is not a journey from darkness to light, and joy is nether its subject nor its goal. But like the Beethoven, it begins in our shared experiences of loss and terror, and resolves in our collective yearning for – and determination to create – a better world.

Please join us for our special 150th Anniversary presentation of Verdi’s Requiem on WETA VivaLaVoce, Wednesday, May 22 at 3:00 PM ET.

PBS PASSPORT

Stream tens of thousands of hours of your PBS and local favorites with WETA+ and PBS Passport whenever and wherever you want. Catch up on a single episode or binge-watch full seasons before they air on TV.